Managing the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest for Its Unique Biodiversity

By Josh Kelly, MountainTrue Public Lands Field Biologist

The conservation importance of the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregion compared to other lands of the United States would be difficult to overstate. This ancient mountain range has long been a mixing zone of northern and southern species and has been a refugium for many lineages since at least the Miocene (Church et al. 2003, Lockstaddt 2013, Shmidt 1994, Walker 2009). As the largest single unit of conservation land in the Southern Blue Ridge, the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest has special significance for maintaining clean water, providing access to recreation and providing habitat for a unique assemblage of plants and animals.

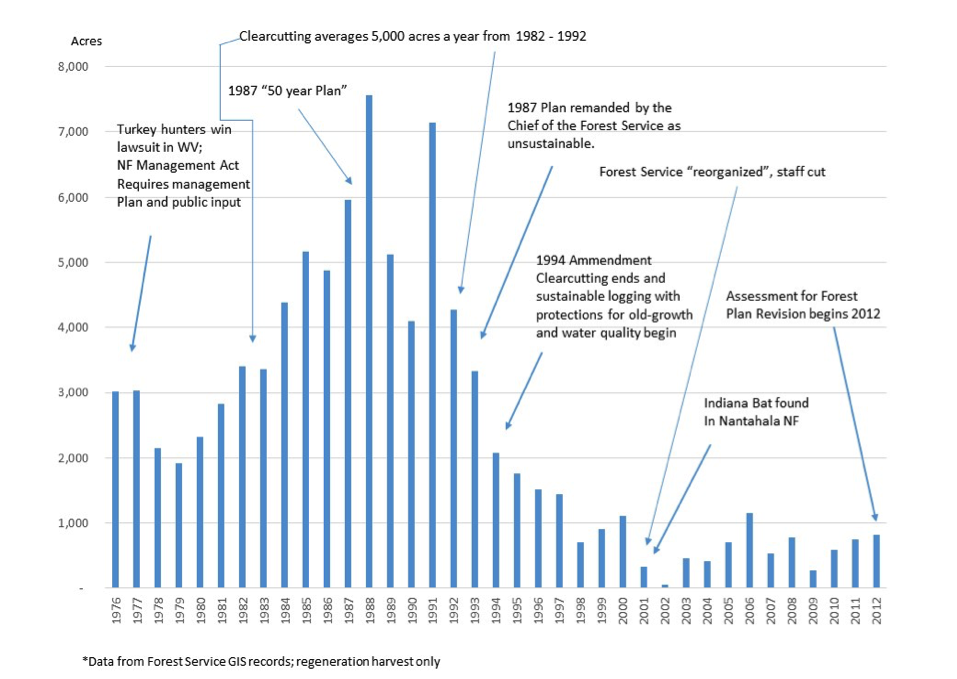

The Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest is currently halfway through the process of revising its Land and Resource Management Plan, which will allocate the million acres of the forest to various emphases of multiple-use land management. The Nantahala-Pisgah last revised its plan with the ground-breaking Amendment 5 in 1994. Amendment 5 mandated 50 and 100 foot stream buffers from logging and road building, increased the acreage of backcountry management areas, created designated patches for old-growth forest restoration and reduced the allowable acreage of harvest from over 7,000 acres annually to around 3,000 acres annually. These were needed reforms following a decade when over 50,000 acres of the Nantahala-Pisgah were clearcut with few protections for water quality and when Forest Service biologist Karin Heiman notoriously lost her job for suggesting that rare species protection was just as important as logging on public land (Bolgiano 1998).

Figure 1: Logging Trends in Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest*

Since 1994, timber harvest declined steadily until 2002 and has plateaued since then. From 2000 to the present, timber harvest has averaged about 800 acres annually – on target to log 8% of the forest over the next 100 years. This follows nation-wide trends in Forest Service management and parallels a trend of declines in early-successional wildlife species (Greenberg et al. 2011). Some of these declines, such as that of the golden-winged warbler, stretch back to the 1950’s (Askins 1993). One of the most controversial and difficult questions facing the Nantahala-Pisgah at this crossroads is how to increase logging to benefit local economies and disturbance dependent wildlife species while protecting one of the temperate world’s greatest concentrations of disturbance sensitive, endemic species. Disturbance dependent species are those that depend on some form or natural or human disturbance like fire, flooding, grazing, wind, insects, or logging to create or maintain habitat conditions they find favorable. Disturbance sensitive species are those that tend to experience population declines or loss of habitat due to natural and/or human disturbances.

The Southern Blue Ridge is among the most biodiverse temperate ecoregions on Earth, and has the highest rate of endemism of all North American Ecoregions North of Mexico (Ricketts et al. 1999). Most of our planet’s biodiversity is composed of specialist, endemic species, and these are the species most vulnerable to extinction (Pimm et al. 1995). There are reputed to be over 258 taxa endemic to the Southern Blue Ridge, many of which are plants and invertebrates (Rickets et al. 1999). Some of the animal lineages most noted for their endemism in the region are salamanders, land snails, fish, crayfish and mussels – all residents of mesic and aquatic habitats that are not typically thought of as disturbance dependent. Indeed, these species are sensitive to disturbance and sedimentation, and the refuge of the Southern Blue Ridge has allowed them to withstand the disturbances of the past; hence their extinction elsewhere and endemism in the Blue Ridge today. Examining patterns of endemism and diversity in the Blue Ridge should help guide land managers in devising conservation strategies for maintaining the region’s biodiversity.

North Carolina is fortunate to have thorough inventories of rare species diversity, courtesy of the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program. Conservation organizations like The Wilderness Society, Wild South and Mountain True have supported additional surveys for biodiversity and remnant old-growth forest over the years. Over 300 rare species deserving conservation call the Nantahala-Pisgah home. Many of the hot-spots for rare species and old-growth forest overlap the largest unroaded areas in the Southern Appalachians – some protected as Wilderness Areas, some as Inventoried Roadless Areas, and some with no formal or administrative protection.

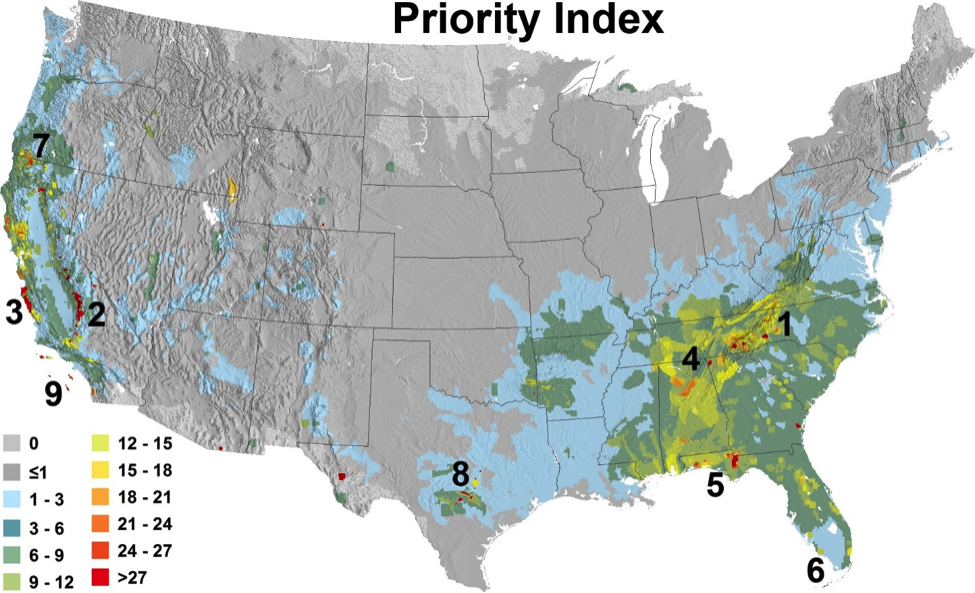

A recent paper in the National Academy of Sciences highlighted the importance and need for conservation in the Southern Blue Ridge (Jenkins et al. 2015). The greatest concentration of locally endemic species in the continental U.S. occurs in the Southern Blue Ridge, and much of this diversity overlaps Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest and lacks formal protection, while being the top priority for additional land protection nationally according to this metric. Two of the hottest spots for local endemic species are in Nantahala National Forest at Cheoah Bald/Nantahala Gorge and the Unicoi Mountains.

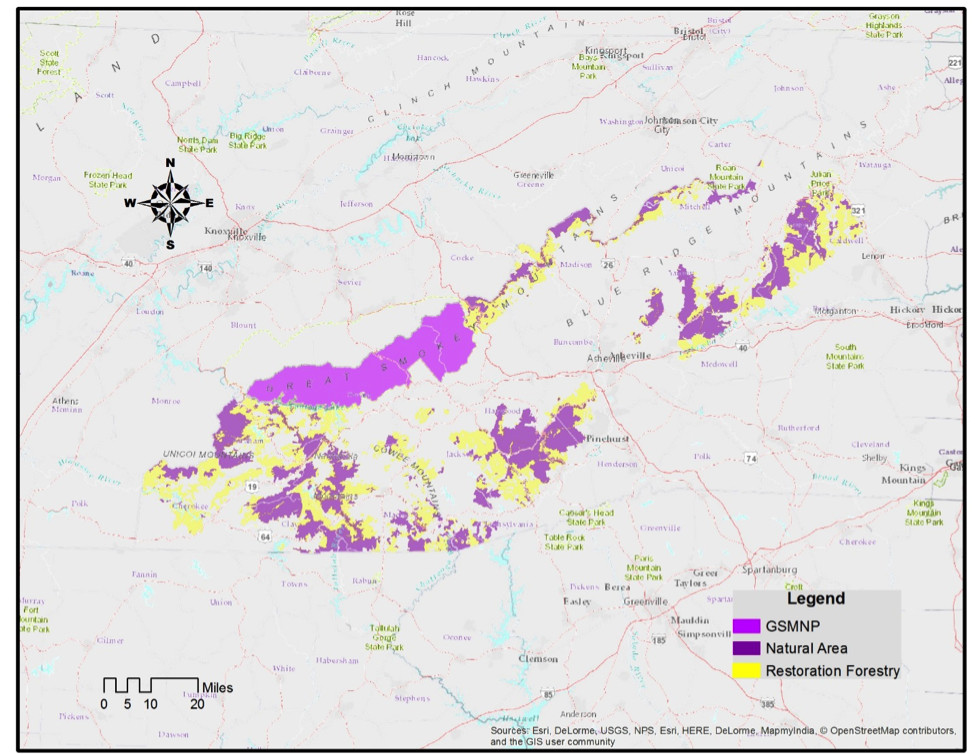

In Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest, all Wilderness Areas, backcountry areas, existing old-growth forest, natural heritage areas, and the Appalachian Trail and Blue Ridge Parkway corridors should be managed to protect and emphasize the special characters they possess. In most cases, this would limit logging, development, and road building in those areas, because those activities pose a threat to the values embodied there – including habitat for specialized, disturbance sensitive species like salamanders. This is a very attainable strategy as these special areas constitute just 55% of the Nantahala-Pisgah, widely regarded as one of the premier units on the National Forest system. For some perspective, this figure is just 5% different from the current land allocation on the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest.

Would managing so much of the forest for unfragmented, older forests and disturbance sensitive species prevent management for disturbance dependent species that need early successional habitat? The answer is no. In the remaining 450,000 acres of the Nantahala-Pisgah, there are over 100,000 acres where forestry techniques could be used to harvest timber, improve forest structure and species composition, create and maintain habitat for disturbance dependent wildlife and benefit local economies. If the maximum timber harvest of the 1994 plan was achieved, a 4x increase over current harvest levels, the 100,000 acres in need would provide over 30 years of work for the Forest Service and the private sector without impacting the most sensitive and highest priority natural areas on the forest. Combining timbering with prescribed fire could provide even more habitat for disturbance dependent wildlife.

Figure 2: Priority Index for Conservation in the Continental U.S. from Jenkins et al. 2015.

Summed priority scores across all taxa and recommended priority areas to expand conservation. 1) Middle to southern Blue Ridge Mountains; 2) Sierra Nevada Mountains, particularly the southern section; 3) California Coast Ranges; 4) Tennessee, Alabama, and northern Georgia Watersheds; 5) Florida panhandle; 6) Florida Keys; 7) Klamath Mountains, primarily along the border of Oregon and California; 8) South-Central Texas around Austin and San Antonio; 9) Channel Islands of California.

Figure 3: Proposed Land Allocation of Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest Revised Land and Resource Management Plan

The Southern Blue Ridge Mountains are one of the most impressive, diverse and intact areas of temperate forest in the World. We are fortunate to live, work, visit, recreate, worship and rejuvenate in these mountains. We all benefit from 100 years of conservation in the Blue Ridge Mountains, but there is much work yet to be done to ensure that our forests remain as diverse, productive, beautiful, and unique as they are today. While Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest is just 22% of the forest land in Western North Carolina, it is an integral part of our lifestyle and heritage. By protecting the best and restoring the rest, we can pass this national treasure on to future generations in better condition than we found it.

Works Cited

Askins, Robert A. “Population Trends in Grassland, Shrubland, and Forest Birds in Eastern North America.” In Current Ornithology, edited by Dennis M. Power, 1–34. Current Ornithology 11. Springer US, 1993

Bolgiano, Chris. The Appalachian Forest: A Search for Roots and Renewal. Stackpole Books, 1998.

Church, Sheri A., Johanna M. Kraus, Joseph C. Mitchell, Don R. Church, and Douglas R. Taylor. “Evidence for Multiple Pleistocene Refugia in the Postglacial Expansion of the Eastern Tiger Salamander, Ambystoma Tigrinum Tigrinum.” Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution 57, no. 2 (February 2003): 372–83. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2003)057[0372:EFMPRI]2.0.CO;2.

Greenberg, Cathryn, Beverly Collins, and Frank Thompson III, eds. Sustaining Young Forest Communities. Vol. 21. Managing Forest Ecosystems. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2011.

Jenkins, Clinton N., Kyle S. Van Houtan, Stuart L. Pimm, and Joseph O. Sexton. “US Protected Lands Mismatch Biodiversity Priorities.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, no. 16 (April 21, 2015): 5081–86. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418034112.

Lockstadt, Ciara Marina. “Phylogeography of American Ginseng (Panax Quinquefolius L., Araliaceae): Implications for Conservation.” 2013 Text. Accessed December 17, 2015.

Pimm, Stuart L., Gareth J. Russell, John L. Gittleman, and Thomas M. Brooks. “The Future of Biodiversity.” Science 269, no. 5222 (July 21, 1995): 347–50. doi:10.1126/science.269.5222.347.

Ricketts, Taylor H. Terrestrial Ecoregions of North America: A Conservation Assessment. Island Press, 1999.

Schmidt, John Paul. Diversity of Mesic Forest Floor Herbs within Forests on the Blue Ridge Plateau (U.S.A.): The Role of the Blue Ridge Escarpment as a Refugium for Disturbance Sensitive Species. University of Georgia, 1994.

Walker, Matt J., Amy K. Stockman, Paul E. Marek, and Jason E. Bond. “Pleistocene Glacial Refugia across the Appalachian Mountains and Coastal Plain in the Millipede Genus Narceus : Evidence from Population Genetic, Phylogeographic, and Paleoclimatic Data.” BMC Evolutionary Biology 9, no. 1 (January 30, 2009): 1–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-25.