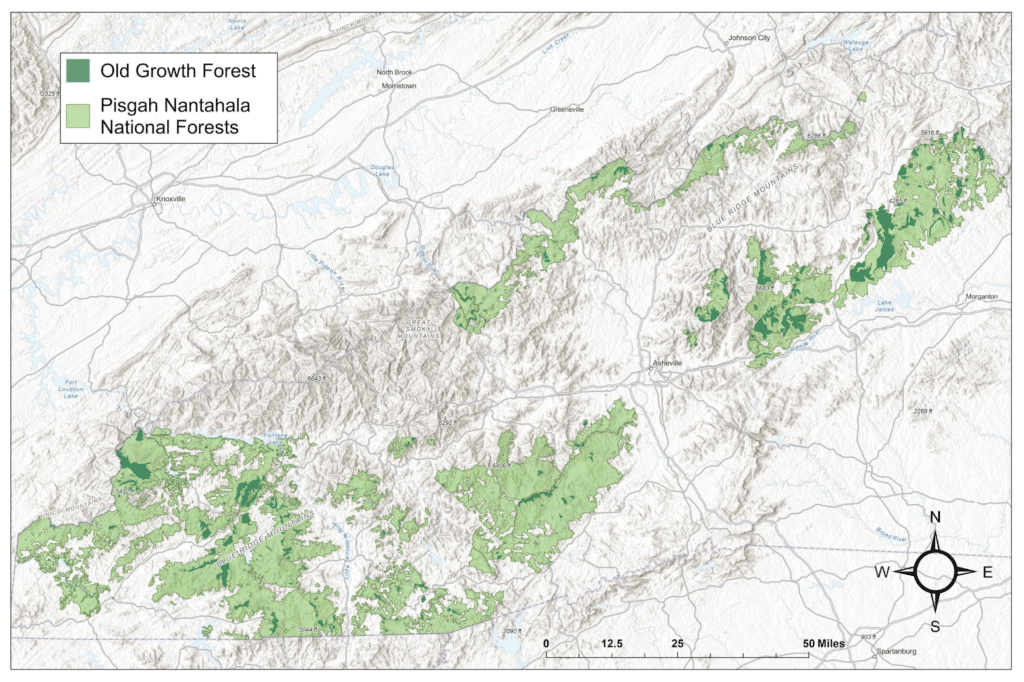

The Southern Blue Ridge Mountains are home to 3.3 million acres of federal public land with 1.7 million acres within Western North Carolina, including the Pisgah, Nantahala and Cherokee National Forests. These forests are ancient in two ways – in length they have been evolving (for millions of years) and the age of trees in certain areas. On average, less than 1% of forests in the whole of the Eastern United States are in old-growth condition, whereas in the Southern Blue Ride, less than 5% of forests are in old-growth condition. In other words, the Southern Blue Ridge is one of the most important regions for old-growth forests Eastern United States, along with the Adirondacks and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area.

Defining Old Growth

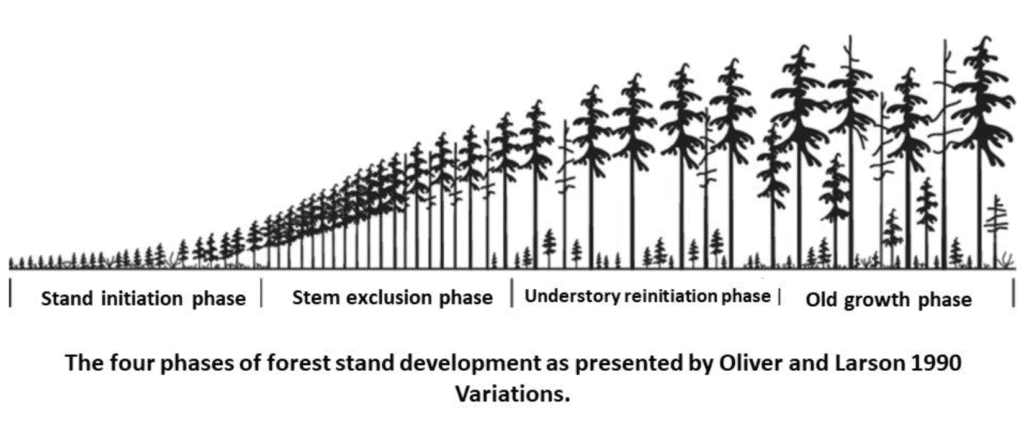

So what is considered old for a tree? And what constitutes an “old-growth forest”? These definitions are somewhat subjective. In general, “old-growth forest” is a stage of forest development, and is not necessarily the “climax” or “final” stage of a forest. The US Forest Service mainly adheres to a linear model of forest development and relies on criteria such as age and density of old trees, density of large trees, and signs of human disturbance, with minimum age of old trees in “old-growth” in hardwood forest types ranging between 100-140 years.

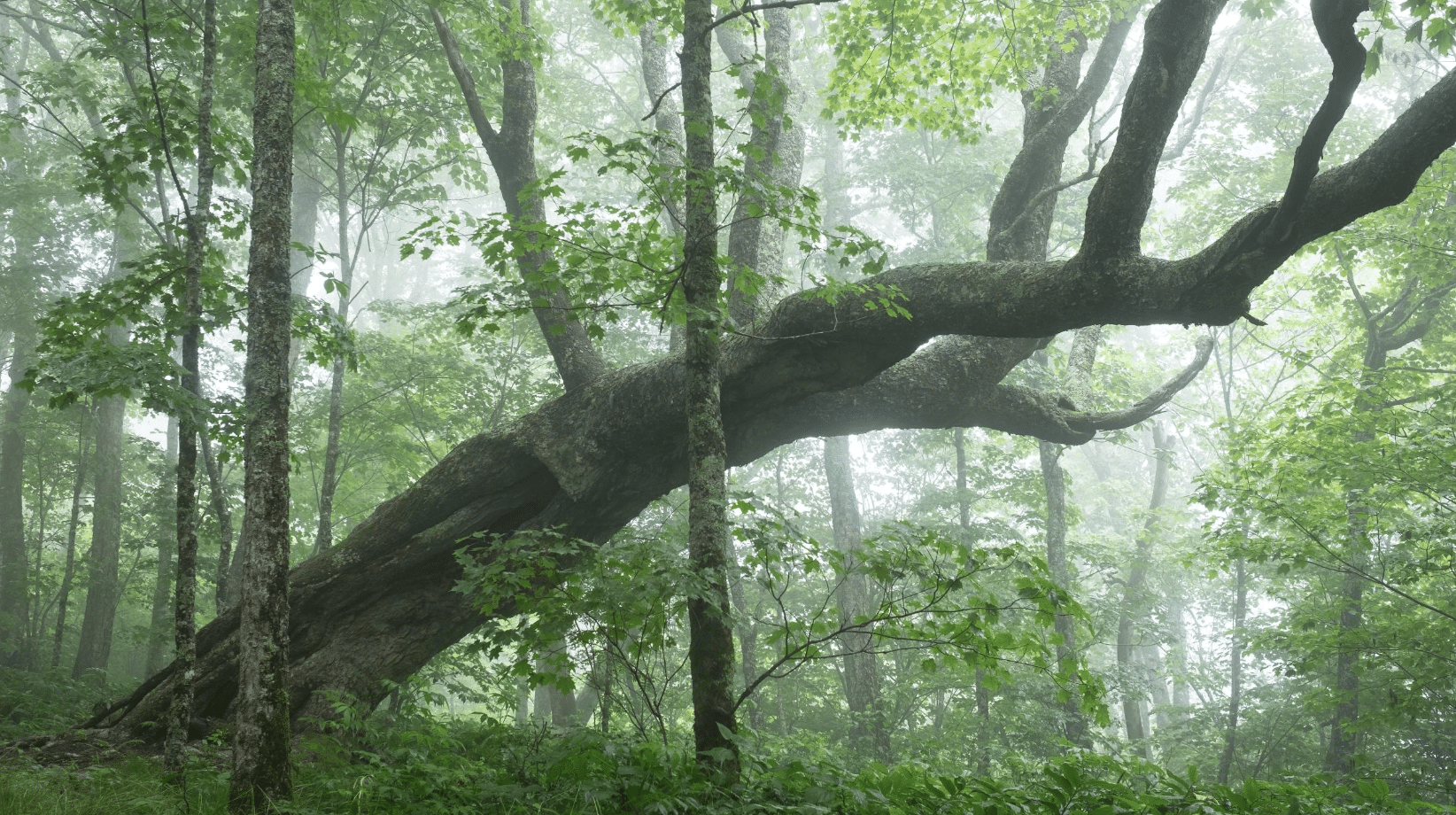

On the other hand, conservationists and ecologists in the region have developed a similar but different definition of old growth that is more non-linear. This methodology also relies on lack of signs of human disturbance and physical attributes like down wood, snags (dead trees that are left upright to decompose naturally) and old trees, but they set the minimum age for old trees at 150 years. In addition, characteristics such as mixed age canopy structure, multiple canopy layers, and woody debris of all sizes in many stages of decomposition, among other factors, are also taken into consideration.

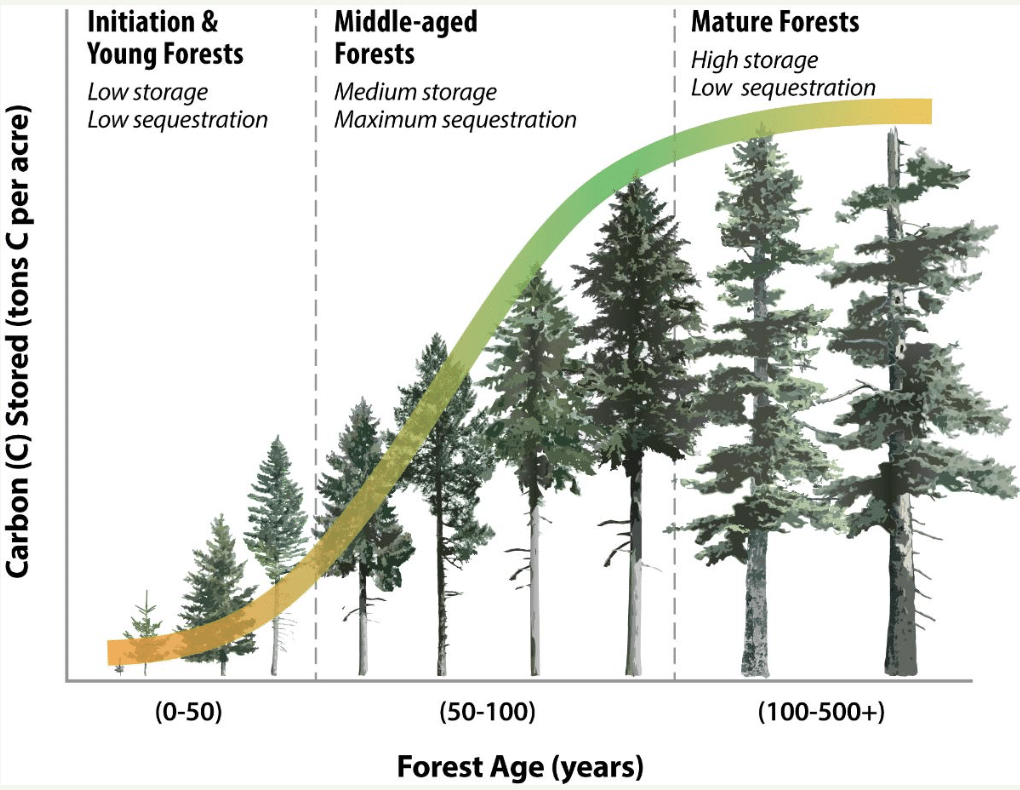

Old-growth forests are important for many reasons. They act as genetic reservoirs for many species, including rare and specialized plants and animals. This creates a higher level of biodiversity, that in turn is a hallmark of a resilient and stable ecosystem. Old-growth forests also protect watersheds, keeping water clean and unpolluted for both animals and humans. They are a living connection to the distant past, and provide models for understanding natural forest dynamics and past weather and climate conditions. That is especially important in a time when our present climate and biosphere is rapidly changing. In addition to providing a way for us to better understand our world, old-growth forests also directly contribute to a more stable and healthy environment and climate by storing massive amounts of carbon dioxide, one of the primary chemicals responsible for global warming, keeping it out of the atmosphere and thus preventing even more extreme climate change.

Unfortunately, some of these ancient forests are still at risk of logging by the US Forest Service.

Forest Service History & Management

It is important to know some of the history of the US Forest Service, the federal agency responsible for overseeing public forests, in order to fully understand the impact of their management plans. These plans are updated every 10-15 years, and recently a new plan was published for the Pisgah-Nanatahala Forests.

Federal forest management first began in 1876 with the Congressional creation of the office of Special Agent in the U.S. Department of Agriculture to “assess the quality and conditions of forests in the United States.” This office was later expanded into the Division of Forestry, and in 1891 the Forest Reserve Act was passed which allowed the President to designate public “forest reserves” in the West. Originally these public lands were under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior, but in 1905 President Theodore Roosevelt transferred them to the Department of Agriculture’s new U.S. Forest Service under the direction of Gifford Pinochot.

| 1876 | Congress creates office of Special Agent in the US Department of Agriculture |

| 1881 | Office of Special Agent expanded into newly formed Division of Forestry |

| 1891 | Forest Reserve Act of 1891 authorizes withdrawing land from public domain as forest reserves managed by the Department of the Interior |

| 1905 | President Theodore Roosevelt transfers forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture under the new US Forest Service |

| 1960 | Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act |

| 1964 | Wilderness Act |

This was in response to decades long concerns about over-exploitation of natural resources driven by unchecked extraction and use. It is important to note that although motivation in this era to conserve public lands was driven in part by a romantic concept of the value of the natural world, the activities of the Forest Service were primarily timber harvesting, road building, and massive fire suppression that disrupted natural fire cycles needed for a healthy ecosystem. Conservation served as a means to increase yields of timber, not to protect ecosystems (the concept of ecology being in its infancy and somewhat controversial).

It was not until the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960 (MUSY) that other resources besides timber (wildlife, range, water, and outdoor recreation) were given consideration in management. The act created what is known as “multiple-use planning” and brought new specialists such as soil scientists and wildlife biologists into the decision making processes of daily land management. However, many people outside the agency saw that management under MUSY changed little on the ground. As Forest Service Historian Dr. Gerald Williams explains, “redefinition of the old ways rather than managing differently on the ground had implications for the controversies regarding forest management [from the 1970s to the 1990s].” With the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, further emphasis was placed on ecological conservation, but the Forest Service opposed this legislation, highlighting the tensions at play within the agency.

While our National Forests are managed more holistically today, the tension between Forest Service timber production and multi-use values continues. This is exemplified by the controversial new Forest Management Plan for Nantahala and Pisgah and the three active lawsuits filed by a coalition of conservation groups, including MountainTrue:

Challenging the Southside Timber Project

In January 2024, the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a lawsuit against the Forest Service, alleging the agency’s plans to log a sensitive area of the Nantahala National Forest violate federal law. Explore the contested area above using the interactive map.

The lawsuit centers around 15 acres of the Southside Timber Project Where the Forest Service plans to log areas near the Whitewater River in the Nantahala National Forest. The landscape boasts stunning waterfalls, towering oak trees, and critical habitat for rare species. Both the Forest Service and State of North Carolina have recognized the area slated for logging as an exceptional ecological community with some of the highest biodiversity values in the state. Because of the scenic beauty and ecological importance of the area, the Forest Service designated it as a “Special Interest Area” in the recently published Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan. Activities like logging and roadbuilding are significantly restricted in Special Interest Areas. The agency is contradicting its own designation with this logging project.

Released last year, the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan falls short on many levels and fails to adequately protect the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. As a result, more than 14,000 people objected to the plan. Limiting logging in the area subject to the lawsuit was one of the few things the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan got right, yet the Forest Service is poised to undermine it by plowing ahead with this reckless and unpopular timber project. We believe that the Forest Service must meet Forest Plan standards for special interest areas, and that will likely mean curtailing logging on this 15 acres. While the particular scope of this suit is small, it has bearing on how the Forest Service will manage Special Interest Areas and other protective designations across the forest.

Incentivizing the Forest Service to Address Climate Change

A second lawsuit alleges the Forest Service’s practice of setting “timber targets” puts the climate at risk, undermines the Biden Administration’s climate goals, and violates federal law. The case centers around the Forest Service’s failure to properly study the massive environmental and climate impacts of its timber targets and the logging projects it designs to fulfill them.

Each year, the Forest Service and Department of Agriculture set timber targets, which the Forest Service is required to meet through logging on public lands. In recent years, the national target has been set as high as 4 billion board feet – or enough lumber to circle the globe more than 30 times. The already high target is expected to increase in the coming years. These mandated targets create backwards incentives for the Forest Service. Forests on public lands provide a key climate solution by capturing and storing billions of tons of carbon. But rising timber targets push the agency log carbon-dense mature and old-growth forests. Logging these forests releases most of their carbon back to the atmosphere, worsening the climate crisis and undermining the Biden administration’s important efforts to protect old growth and fight climate change. In a time when restoration is needed on as many acres as possible, the timber volume target incentivizes logging the biggest trees on fewer acres, rather than thinning smaller trees over a greater area.

Despite their significant and long-lasting impacts on our climate and forests, the Forest Service has never assessed or disclosed the climate consequences of its timber target decisions. The Forest Service has the tools and research to address climate change and is mandated to consider the impacts of its policy as it relates to climate change. This is evidenced by the newly developed Forest Service Climate Risk Viewer .

Advocating for the Protection of Endangered Species

Lastly, a third lawsuit has been filed against both the US Forest Service and the US Fish & Wildlife Service for violations of the Endangered Species Act committed during consultation and development of the Biological Opinion on which the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan relies. This legal action seeks to protect endangered wildlife that are threatened by the new Forest Plan, which prioritizes commercial logging in habitat that is critical for the survival of several species.

The flawed Forest Plan jeopardizes not only the endangered northern long-eared bat, Indiana bat, Virginia big-eared bat, and the gray bat but also impacts species like the little brown bat and the tricolored bat, which are currently being considered for the endangered species list. Our lawsuit aims to rectify the inaccuracies, incomplete data, and flawed analysis that underpin the current plan, ensuring a more sustainable future for these critical habitats and the wildlife that dwell there.

To be clear, our goal with any of these lawsuits is not to stop logging on the national forest. However, we believe logging should be limited in areas known to be habitat for imperiled species. Unfortunately, the new forest plan allows run-of-the-mill logging in many of the healthiest and most sensitive habitats.