Harvey’s Toxic Wake

Hurricane Harvey had another dangerous effect: flooded superfund sites. French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson reports back from Houston.

September 15, 2017

Bruce and I, alongside Savannah Riverkeeper Tonya Bonitatibus, are a last-minute crew assembled by the Waterkeeper Alliance to respond to the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. We’re in Houston to assess the hurricane’s impact on the many oil, gas, chemical and industrial sites in the region — after receiving over 50 inches of rain in many areas, there is real concern about stormwater runoff, overflowing wastewater plants, and spills and leaks from the massive oil and gas facilities near Houston’s waterways.

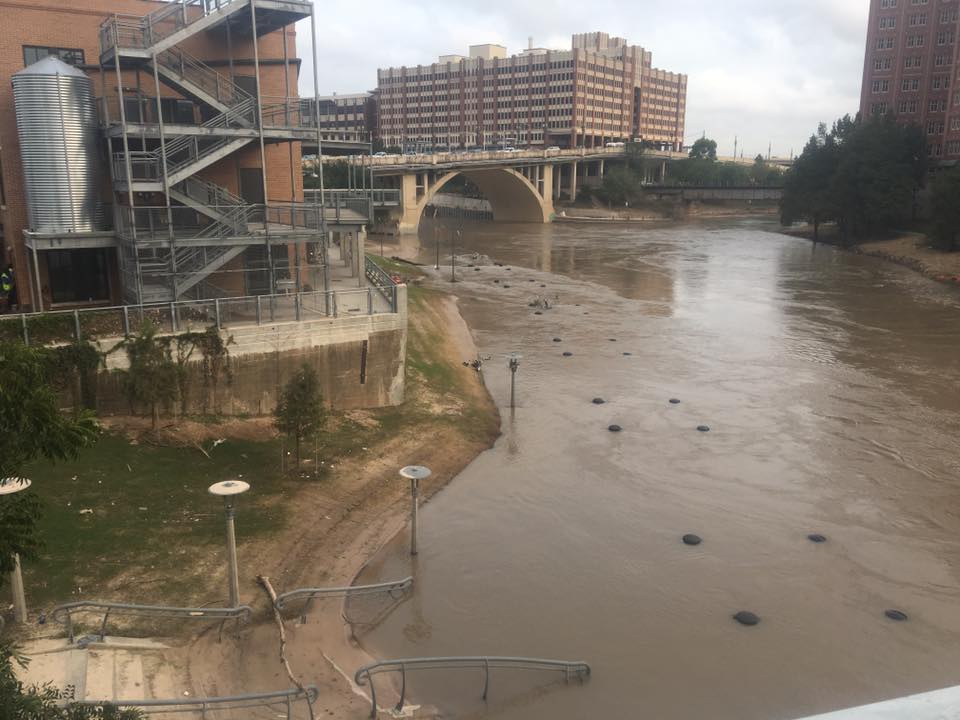

The dichotomy of the storm is quickly evident. Our downtown accommodations show no sign of Harvey’s impacts, but as I walk a few blocks to assess the Buffalo Bayou, I see workers hosing off the side of a building. They show me a spot on the wall about 35 feet above the water, where the floodwaters reached during the storm. We witness neighborhoods completely devastated by the flooding, while homeowners elsewhere are planting flowers and mowing their lawns like nothing ever happened. Bruce explains that this storm was “more of a rain event than a wind event, and it was like a lot of floods: you’re either in it or you’re not.”

Being “in it” not only meant that your home had flooded and belongings had been destroyed. Too often, it meant the floodwaters brought a toxic stew into your neighborhood and your house.

On one of our monitoring trips, we examined the area’s many superfund sites. Houston has a long history of heavy industry and pollution, and therefore is home to some of the most toxic sites in the country. One of those sites is the French LTD. It sits close to the San Jacinto River, directly next to a low-income mobile home community that was completely devastated by the floodwaters. Trailers there are overturned and cars are underwater. There is no indication that anyone has been here to inspect the toxic water pollution caused by the storm.

Bruce and I paddle down Green’s Bayou in sea kayaks in an attempt to lay eyes on the impact of the storm from the river. As we ease our way down the Bayou towards the heart of the oil and gas facilities, Bruce says it won’t be long before we get stopped. And we do get stopped — not by the police, but by giant barges tied together to block access to the downstream facilities. We take in toxic smell after toxic smell, some so strong that I get a headache. Bruce calls out the names of these toxic substances as if we are out birdwatching. The smell becomes overpowering as we paddle by Arkema, the same company whose toxic chemicals exploded in another area of Houston. “We probably should have brought our respirators,” Bruce says casually. “This smell could kill you if it were a bit stronger.”

Bruce’s calm response to potentially being killed by toxic chemicals while kayaking comes from a career spent around the oil and gas industry. A career that has seen a lifetime’s worth of oil and gas pollution, lakes of chemicals sunken into the ground, and chemical explosions.

The risk of dying from a toxic chemical exposure is not something I am accustomed to when I go paddling. But in Houston — ground zero for the oil and gas industry — it is a way of life. It’s illegal for these chemicals to leave the property, Bruce says, but there isn’t much incentive to stand up to the multi-billion dollar oil and gas giants like ExxonMobil and BP.

When our boat patrol is finished, we drive through a residential neighborhood bordering the ExxonMobil refinery. Many of these people live and breathe the toxic byproducts of our country’s fossil fuel addiction every day. The scenes we pass of kids riding bikes and playing on swing sets would be totally normal, if it weren’t for the backdrop of methane flares and toxic air emissions just over their heads.

“During Harvey, the released toxins were so intense that a ‘shelter in place warning’ was issued for this neighborhood in Baytown,” Bruce explains. “They even advised against using air conditioners, to prevent toxic chemicals from being drawn into homes.” I fully believe this, because my skin has started to burn from the water that splashed all over us during the boat patrol.

“This looks like the future scene from the Terminator movies, where the robots have destroyed the Earth,” I tell Bruce, only half-kidding.

For a moment, I think that maybe this area should remain a sacrifice zone, so the rest of the country can burn oil and gas. But when I look back at the blue herons taking off from the discharge of oil refineries, and see kids riding bikes under the shadows of methane flares, I remember that this fight to protect the waterways is worth fighting, and that it is exactly what Waterkeepers do best.

Waterkeepers take on David versus Goliath fights every day. This is a fight for the future — not only for the future of the people and waterways around Houston, but for the future of our planet. The oil and gas industries are strangling our ability to develop a clean energy future. A future where people can relax in their yards without fear of toxic pollution, paddle and swim in their waterways, and use renewable energy that doesn’t contribute to climate change. This is a battle worth fighting, and a battle the Bayou City Waterkeeper and Waterkeeper Alliance intend to win.