MountainTrue is Objecting to the Revised Forest Plan for the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forests. These are our Reasons.

After over eight years of work and more than 25,000 public comments, the United States Forest Service (USFS) has released its Revised Forest Plan for the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. Comprised of a 360-page plan, a 738-page Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), and more than 1,000 pages of appendices to the FEIS, the Forest Plan provides a strategic framework for the next 20 years of management in the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. We offer this critique of the Revised Forest Plan so that our members and the general public can better understand the plan and its implications and why and on what grounds MountainTrue is filing formal objections to the plan.

MountainTrue is a longtime advocate for the sustainable management and conservation of Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. Our members led the successful campaign to stop the practice of clear-cutting in the forests, and our staff conducted the first inventory of old-growth stands in the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. MountainTrue’s Public Lands Team members are intimately involved in protecting these public lands: monitoring timber sales to ensure old-growth forests, water quality, and sensitive habitats are protected, restoring and protecting native habitats by treating invasive non-native plants and pests, and helping the Forest Service design and implement restoration projects.

Our views are influenced by our intimate history with these national forests, but also by our membership in the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Partnership (Partnership) and our endorsement of the Forest Plan Alternative provided to the USFS by the Partnership in June 2020.

Table of Contents

- Land Allocations Unnecessarily Prioritize Timber at the Expense of Conservation Areas

- The Old-Growth Network Shell Game

- The “such as, but not limited to” Timber Loophole

- Nantahala National Forest is Treated as a Second-class Forest

- Highly Rated Natural Heritage Natural Areas Remain Vulnerable to Timbering

- Water Quality at Risk from Logging without Steep Slope Protections or Adequate Road Maintenance

- Forest Service Drew Management Areas Around Controversial Projects

- Curious Omissions Among the Designations

- Sensitive Wildlife Could Be Impacted by Faulty Assumptions

- Recreation: Improvements to Trail Access but Too Restrictive to Other Activities

Protect Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests

Support our Resilient Lands program and help protect the places we share.

The Partnership consists of 27 active member and affiliate organizations representing conservation, economic development, forest products, recreation, water, and wildlife interest groups. The Partnership worked collaboratively to negotiate the outcomes presented in the Forest Plan Alternative. The Partnership hoped the heavily negotiated compromise would resolve the Draft Forest Plan’s key issues, streamline its implementation, and reduce future conflicts with the Forest Service and between user groups.

There were two key innovations in the Partnership’s Forest Plan Alternative. First, the group identified the largest broadly supported area for timber production — approximately 500,000 acres or nearly half of the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests, where timbering could be done without impacting important recreation and conservation areas. The second innovation was the linking of objectives that are in tension with one another. For example, the Partnership Alternative required that roads and trails in a geographic area be well-maintained before the Forest Service constructed new ones, and base levels of timber harvest would have to be accomplished before any new Wilderness designation was sought. These innovative ideas would have incentivized collaboration.

The Partnership’s Forest Plan Alternative was a painstakingly negotiated road map that included maps and specific consensus recommendations that would have achieved:

- the protection of old-growth stands, natural heritage natural areas, backcountry wilderness, and other sensitive recreation areas;

- the protection, maintenance, and expansion of recreation areas and trail systems;

- the creation of new young forest habitats at biologically significant levels for the benefit of wildlife and hunters alike;

- and, at the same time, meet the Forest Service’s goals to increase timbering.

The Forest Services’ previous management plan suffers from some of the same issues as the proposed plan, namely inefficient management area allocation, and its implementation resulted in public controversy and conflict. Forest interests groups — such as timber companies, hunters, recreators, and conservationists — often perceived themselves to be in competition with one another when timber harvest was proposed in areas with multiple high values. The result was gridlock and damaged ecosystems: the Forest Service trampled on biologically sensitive areas without meeting their timbering goals, and forest interests groups blamed each other.

This was supposed to change with the 2012 Planning Rule adopted by Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, which sought to modernize forest management by addressing the “evolving scientific understanding of approaches to land management, changing social demands, and new challenges such as changing climate.”

At the core of the new planning rule was a commitment to a collaborative process that would ensure transparency and effective public participation. In its preamble, the Department of Agriculture states that the new rule “emphasizes providing meaningful opportunities for public participation early and throughout the planning process, increases the transparency of decision-making, and provides a platform for the Agency to work with the public and across boundaries with other land managers to identify and share information and inform planning.” In this spirit, the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Partnership was established and painstakingly negotiated its consensus Plan Alternative.

Unfortunately, the Forest Service declined to adopt or even fully analyze the Partnership proposal as an alternative. Instead, the Forest Service has proposed a plan that offers vague assurances while placing important conservation areas in areas designed for timbering, expanding the road network without providing plans to maintain it, and establishing loopholes that undermine the protection of the conservation areas that are established by the plan. Many of our concerns relate to the potential for poorly conceived timber harvest to impact water quality, steep slopes, and areas critical for the preservation of biodiversity. We want to emphasize, though, that we fully support meeting the timber harvest goals agreed to by the Partnership, even going so far as to compromise in supporting rotational timber harvest in the consensus suitable timber base.

While there are some bright spots in the Forest Service’s Revised Plan — such as an increase in active fire management, recommendations for Wild and Scenic Rivers, and a recommitment to adequate streamside zones — they are far outweighed by its shortcomings:

Land Allocations Unnecessarily Prioritize Timber at the Expense of Conservation Areas

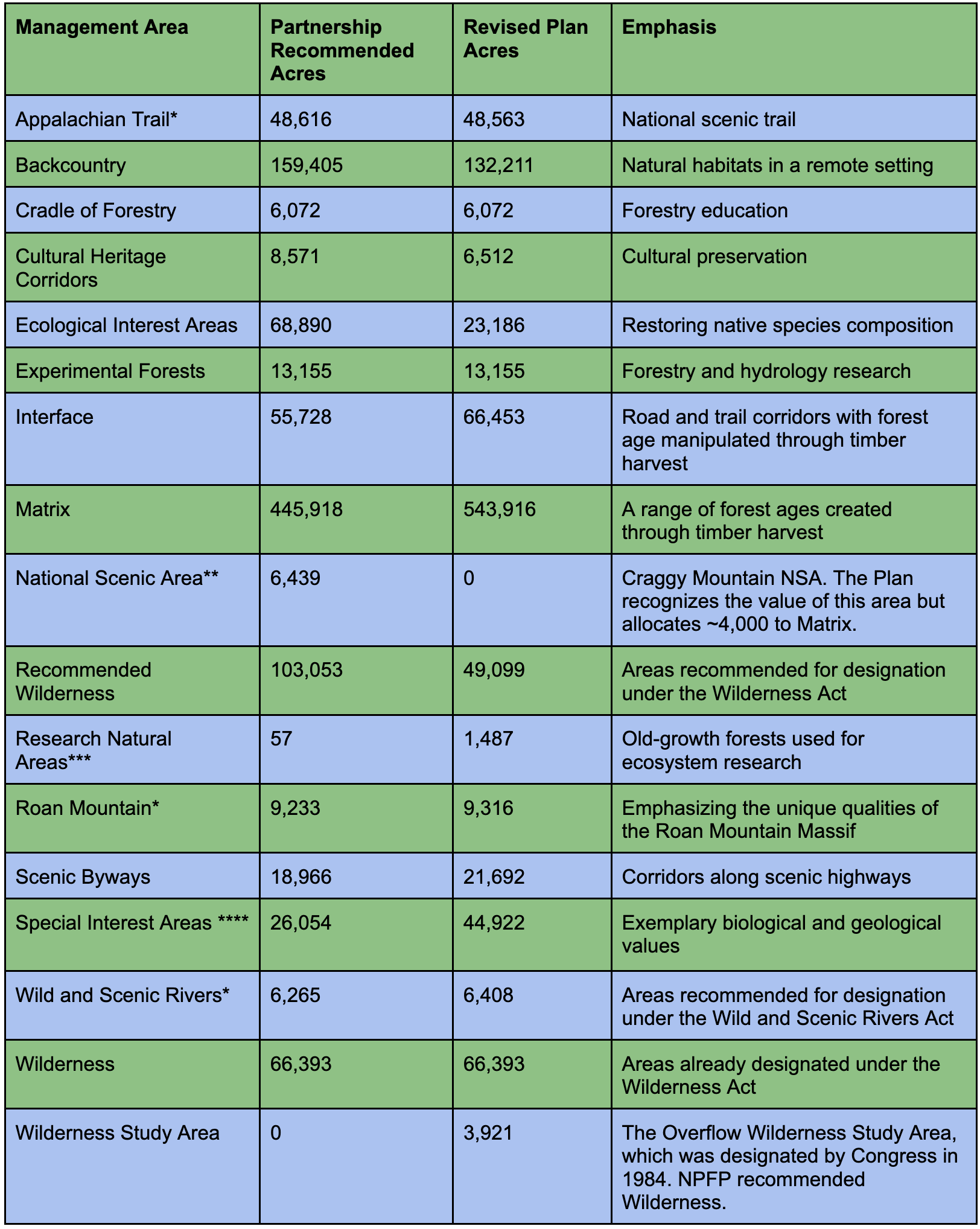

The Forest Services divides the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests’ 1.045 million acres into 17 unique management areas with specific management needs in the Revised Forest Plan. Because many ecological communities exist at various elevations, the Forest Service’s management approach must be specialized and place-based to support each management area’s abundant biodiversity.

Ensuring the efficacy of the Forest Service’s proposed place-based management area allocations was a primary objective of the Nantahala Pisgah Forest Partnership as it negotiated its Forest Plan Alternative. Instead of adopting these recommendations, the Forest Service puts the ecological well-being of more than 100,000 acres of important conservation areas at risk. These conservation areas include North Carolina Natural Heritage Areas, existing old-growth forests, and potential Wilderness Areas.

In the chart below, you will see that the Partnership identified 501,646 acres (or roughly half of the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forests) to be included in Matrix and Interface — the two management area designations where the emphasis is placed on timber harvesting/production. This is more than sufficient for the Forest Service to meet its goal of harvesting up to 3,200 acres per year.

*The difference in acreage is not significant

**While the Forest Service did not include a specific Management Area for the proposed Craggy Mountain National Scenic Area, it does recognize the scenic value of an approximately 10,000-acre core.

***The Middle Creek Research Natural Area was included in the Black Mountains Recommended Wilderness by the Partnership

****Special Interest Areas are largely composed of North Carolina Natural Heritage Natural Areas. The Partnership recommended that most of these areas either be allocated to management areas not suited for timber production or protected through Forest Plan Standards.

The Forest Service’s Revised Plan includes an additional 108,723 acres in their Matrix and Interface allocations. All but roughly 8,000 (7,823) acres come from conservation areas that include North Carolina Natural Heritage Areas, existing old-growth forests, and potential Wilderness Areas.

As it currently stands, at least 12,000 acres of inventoried, existing old-growth forest, more than 45,000 acres of Natural Heritage Natural Areas ranked “High” to “Exceptional” by the NC Natural Heritage Program, and over 100,000 acres of important conservation areas have been designated for “regularly scheduled timber harvest” within the Matrix and Interface allocations. Not all of the important conservation values designated to suitable management areas will be proposed for logging, but some certainly will.

This regrettable management area allocation prioritizes commercial timber harvest projects that will negatively impact these important conservation areas, making timber harvest unnecessarily complicated, controversial, and damaging.

The Old-Growth Network Shell Game

Old-growth forests are vital for native species, scientific study, aesthetic and spiritual reasons, and are crucial for sequestering and storing carbon that would otherwise contribute to climate change. Before the industrial age, most of the forest in the Southern Blue Ridge were old-growth forests with complex structures and a vast diversity of tree sizes and ages. A wave of logging for national and international markets from 1880-1940 removed most of the original forest, and today only 10% of Nantahala and Pisgah and just 3% of the region as a whole are believed to be in old-growth condition. The analysis in the Revised Forest Plan acknowledged that approximately half of the tree canopy of Nantahala and Pisgah would have been in old-growth condition prior to European colonization.

The Forest Service has touted the Revised Plan as an improvement for old-growth forests because it designates approximately 265,000 acres for old-growth management (ROD p.22). While this is a big number, it’s important to note that all but 44,000 acres of old-growth designations are already protected at a higher level, such as by the Wilderness Act, the Inventoried Roadless Rule, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, Research Natural Areas, and others. So, these are primarily designations of convenience — in the sense that they are already off-limits to logging rather than because of their outstanding values.

MountainTrue and our predecessor organization, the Western North Carolina Alliance, began mapping the old-growth forests of Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests in 1994. Through that work, we have documented over 90,000 acres of old-growth on Forest Service lands. We shared that inventory with the Forest Service, and unfortunately, over 12,000 acres of field-verified old-growth remains in timber production management areas, where the plan direction is to create young forest through timber harvest.

What’s more, 110,000 acres of the designated old-growth network in the plan is relatively young — less than 100 years old, according to Forest Service Records. The Forest Service claims that by designating middle-aged forests, they are ensuring the development of old-growth in the future, even though they are leaving much more worthy forests unprotected.

The network of old-growth designations begins to look like a shell game when you realize that thousands of acres of small patch old-growth designations made in the last 28 years were not included in the Revised Plan. The Forest Service seems to be setting up a precedent where they can open up more mature, lucrative forests that had previously been “designated old growth” to logging now, and only protect middle-aged forests until the next plan — when they could theoretically open up some of those more mature stands to timbering. Examples of this dynamic include very high-quality designations that were made and subsequently discarded in the Upper Santeelah and Shope Creek Projects but have now been allocated to a timber production management area.

Another major concern is that the Forest Service is providing project staff and district rangers with too much flexibility and decision-making power to cut the last remnants of existing old-growth forests under their stewardship. The Record of Decision states:

“The District Ranger, or the Forest Supervisor for multi-district projects, will retain the option of how to manage old trees, old stands, or old growth forest patches in the project itself, depending on the management area direction, site-specific conditions, and ecological needs in the area” (ROD pp. 44-45, emphasis added)

In recent years, we have provided input on numerous projects where the Forest Service proposed to cut existing old-growth forests and only relented under vigorous public pressure (see the Globe Project, Big Choga Project, Haystack Project, Harmon Den Project, Mossy Oak Project, Buck Project, and more).

Old growth takes centuries to develop, and the fact that the Forest Service discarded thousands of acres of designations from the last plan, so casually and without analysis or effort to include them in the new plan, needs to be corrected. And protecting existing old-growth forests should not be up to the discretion of Forest Service staff at the project level. It is crucial that the Forest Service not just manage for future old growth but also protect the old-growth forests we have now. To be meaningful, old-growth designations need to be nearly permanent.

The “such as, but not limited to” Timber Loophole

The USFS has historically focused on cutting and growing trees, emphasizing active forest management that prioritizes timber harvest revenues over economic activity and public benefits derived from outdoor recreation, wildlife, and clean water. This emphasis is reflected in the binary designation of Management Areas as either “suitable” or “unsuitable” for timber production:

TIM-DC-06 Lands identified as suitable for timber production have a regularly scheduled timber harvest program that contributes to forestwide desired conditions. Rotation ages needed to meet restoration and habitat objectives for young forest and future middle-aged mast producing forests are also compatible with the production of sawtimber and pulpwood products.

TIM-DC-07 Land identified as not suitable for timber production, but where timber harvesting could occur for other multiple-use purposes, has an irregular, unscheduled timber harvest program. Harvest meets management direction and desired conditions for the area while providing services and benefits to the public.

(Forest Plan Page 91)

Now, let’s consider the Forest Plan’s definition of what is allowed in management areas classified as “not suitable for timber production.” The sections we have bolded create a loophole big enough to drive a logging truck through.

TIM-S-02 While timber harvest can occur on lands both suitable and not suitable for timber production, unless otherwise specified in management area direction, it can only occur on lands not suitable for timber production when it is determined that timber harvesting activities are needed for salvage or to protect multiple use values other than timber production, such as, but not limited to:

(1) addressing issues of public health or safety;

(2) reducing hazardous fuels and managing wildfire;

(3) restoring or maintaining a terrestrial or aquatic ecological system or wildlife habitat over time;

(4) restoring or maintaining habitat for federally threatened and endangered animals or plants and SCC;

(5) harvesting dead or dying trees due to fire, natural disturbances, insects, and disease; (6) restoring or maintaining recreation, scenery, or transportation management;

(7) accommodating special use permits and outstanding rights; or

(8) for research, demonstration, or education purposes.

(Forest Plan page 91, Emphasis added)

The use of “such as, but not limited to” negates the purpose of the list that follows by allowing timbering for any reason that a ranger or project manager may contemplate in the future. As close observers of Nantahala and Pisgah National Forest know, every single timber sale in the past 40 years has purported to “restore or maintain terrestrial wildlife habitat.”

There is a common thread throughout the Forest Plan of delegating most decision-making to individual rangers at the project level with overly broad language. As it stands now, the binary distinction between what management areas are suitable and unsuitable for timber harvest is rendered moot by a set of criteria that neglects to exclude much of anything. Essentially, this makes no part of the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests off-limits to logging. For there to be a distinction between the suitable and unsuitable management areas, the Forest Service must strengthen this language.

Nantahala National Forest is Treated as a Second-class Forest by the Forest Service

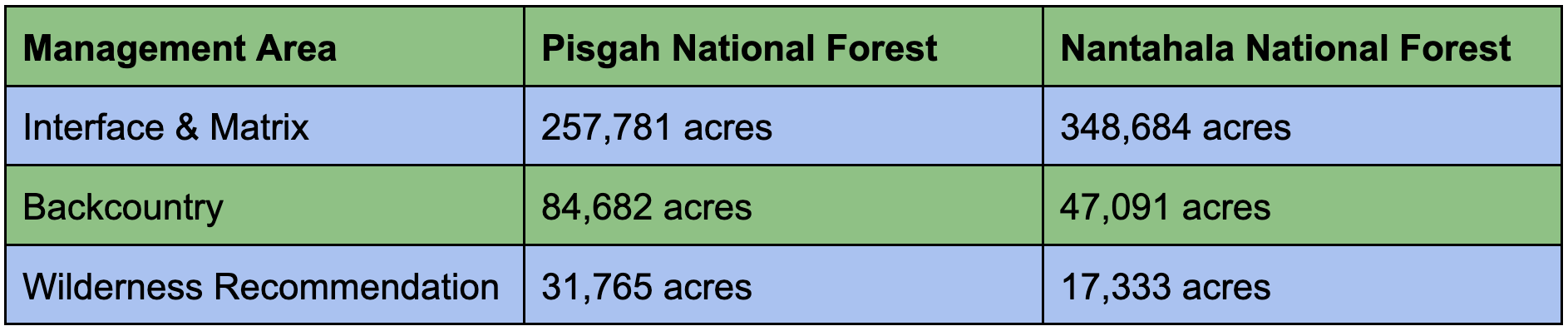

Nantahala and Pisgah National Forest have equivalent acreages, physical features, biological values, and both are beloved by the public. Why then is the Forest Service proposing to manage the two forests so differently based on their management area allocations?

The USFS plan places approximately half (50.3%) of Pisgah National Forest in the Interface and Matrix designations, where active timber production is a primary or secondary goal. Nearly two-thirds of Nantahala National Forest, on the other hand, is open to rotational logging.

Of the two forests, Nantahala National Forest is certainly the more remote, and more of its acreage qualifies for the backcountry management allocation. Why then, is so much more land dedicated to timber production in Nantahala National Forest versus Pisgah National Forest? The USFS is proposing to only place 8.9% of the Nantahala National Forest in Backcountry designation (where logging is not supposed to happen) compared to an already modest 16.5% in Pisgah National Forest.

There is no analysis in the Forest Plan to support this discrepancy. We are concerned that this is the result of arbitrary decision making on the part of the Forest Service and, once again, a desire to delegate the decisions that should have been made by the Forest Plan, such as whether or not to cut old-growth forest, to District Rangers at the project level. If the Forest Service had adopted a more balanced plan, similar to the Partnership alternative, the land allocation would be more equitable for Nantahala National Forest.

Highly Rated Natural Heritage Natural Areas Remain Vulnerable to Timbering

Every state in the United States has a Department of Natural Heritage whose mission is to catalog and preserve the natural diversity within the state’s boundaries. North Carolina has had a better-than-average Natural Heritage Program, though at times, protecting natural resources has been politically controversial, despite being overwhelmingly popular.

North Carolina’s Natural Heritage Program has inventoried Natural Areas in 97 of the state’s 100 counties. Many of North Carolina’s very best Natural Areas are situated within the boundaries of Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. Unfortunately, the Forest Service has historically been ambivalent, at best, about these important areas. More recently, the Forest Service has acknowledged that some of these areas deserve special attention.

Natural Heritage Areas have a five-tiered ranking that categorizes natural values as General, Moderate, High, Very High, and Exceptional. In one of the bright spots of the Revised Plan, the Forest Service chose to place most of the acreage of Natural Heritage Areas rated as Exceptional in Special Interest Area Management. Unfortunately, over 45,000 acres of Natural Heritage Areas rated as High, Very High, and Exceptional were placed in timber production management areas, ensuring that some of these areas will continue to be proposed for timber sales. To reduce the potential for project-level conflict, the Forest Service should place these remaining highly rated natural areas in protected management areas.

Water Quality at Risk from Logging without Steep Slope Protections or Adequate Road Maintenance

The Forest Plan is a mixed bag when it comes to protecting water quality. On the positive side, the new plan maintains the 50’ buffers on intermittent streams and 100’ buffers on perennial streams introduced in 1994. In these areas, trees must be retained and heavy equipment is excluded to prevent erosion and sediment pollution from stormwater runoff.

On the other hand, the Forest Service is proposing to remove the prohibition on ground-based logging for steep slopes, providing only vague assurances that new technology would prevent harm. In the previous plan, logging on slopes over 40% required aerial logging systems that lifted trees off the ground and negated the need to build logging roads on steep slopes. The revised plan proposes to remove this requirement. There may be new technologies that would be as protective as aerial logging methods, but the plan should continue to prohibit the creation of harvest roads on steep slopes and have stronger standards as to how logging methods on steep slopes are chosen.

Finally, sedimentation from forest roads is the primary threat to water quality and aquatic wildlife, and the Revised Plan should have made meaningful progress towards decreasing sedimentation from roads. Instead, the Forest Service is projecting 6 miles of road construction annually to meet Tier 1 timber harvest goals and an additional 4 miles to meet Tier 2 goals, while declining to produce a plan for meaningfully maintaining the 2,200 miles of roads already under Forest Service management. It would be more logical and more protective of water quality to require road maintenance goals from Tier 1 to be met before moving to Tier 2 levels of road building.

Forest Service Drew Management Areas Around Controversial Projects

If the forest plans are the map given to Forest Service personnel to manage the land and water, then the projects proposed by Forest Service staff are the vehicles to get to the destination or the “desired conditions” identified in the Forest Plan. For the past 40 years, the Forest Service has struggled to propose vegetation management projects within the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests that have been broadly acceptable to timber, recreation, and conservation interest groups alike.

Such controversial projects can damage important conservation areas, as occurred in the Pisgah Ridge Natural Heritage Area in the Courthouse Creek Project. In Courthouse Creek, logging on steep slopes caused severe erosion that led to a landslide during Tropical Storm Fred and turned Courthouse Creek the color of chocolate milk during the average rainy season of 2017. Such projects also tend to be less efficient and require a large amount of planning and analysis time. Only one-third of the approved timber harvesting at Courthouse Creek was ever accomplished.

Erosion and logging at Courthouse Creek. Photos by Nicholas Holshouser.

There is a spate of recent projects that were approved under the old forest plan but will be implemented under the new plan. Some like the Twelve Mile Project had consensus support and approved over 1,800 acres of timber harvest and wildlife habitat while protecting old growth and Natural Heritage Natural Areas. Others, like Buck and Southside, were very controversial because they proposed logging old growth, areas inventoried as potentially suitable for Wilderness Designation, and Natural Heritage Natural Areas, while also building miles of roads across steep slopes. Some projects, like Crossover and Lickstone, are still in development but have a high potential for controversy because of these same issues.

Reviewing the Forest Plan, it appears that the Forest Service has drawn management area boundaries in all of those projects that would support the controversial steep slope logging and excessive road building (8 miles) of Buck, the old-growth logging of Southside, and potential logging of old-growth and backcountry areas in Crossover. We believe that the Forest Service should not be building the new plan around poorly designed old projects, but instead, create a new plan that is consistent in its application and leads to more broadly supported and efficient projects.

Curious Omissions Among the Designations

Wilderness Designations

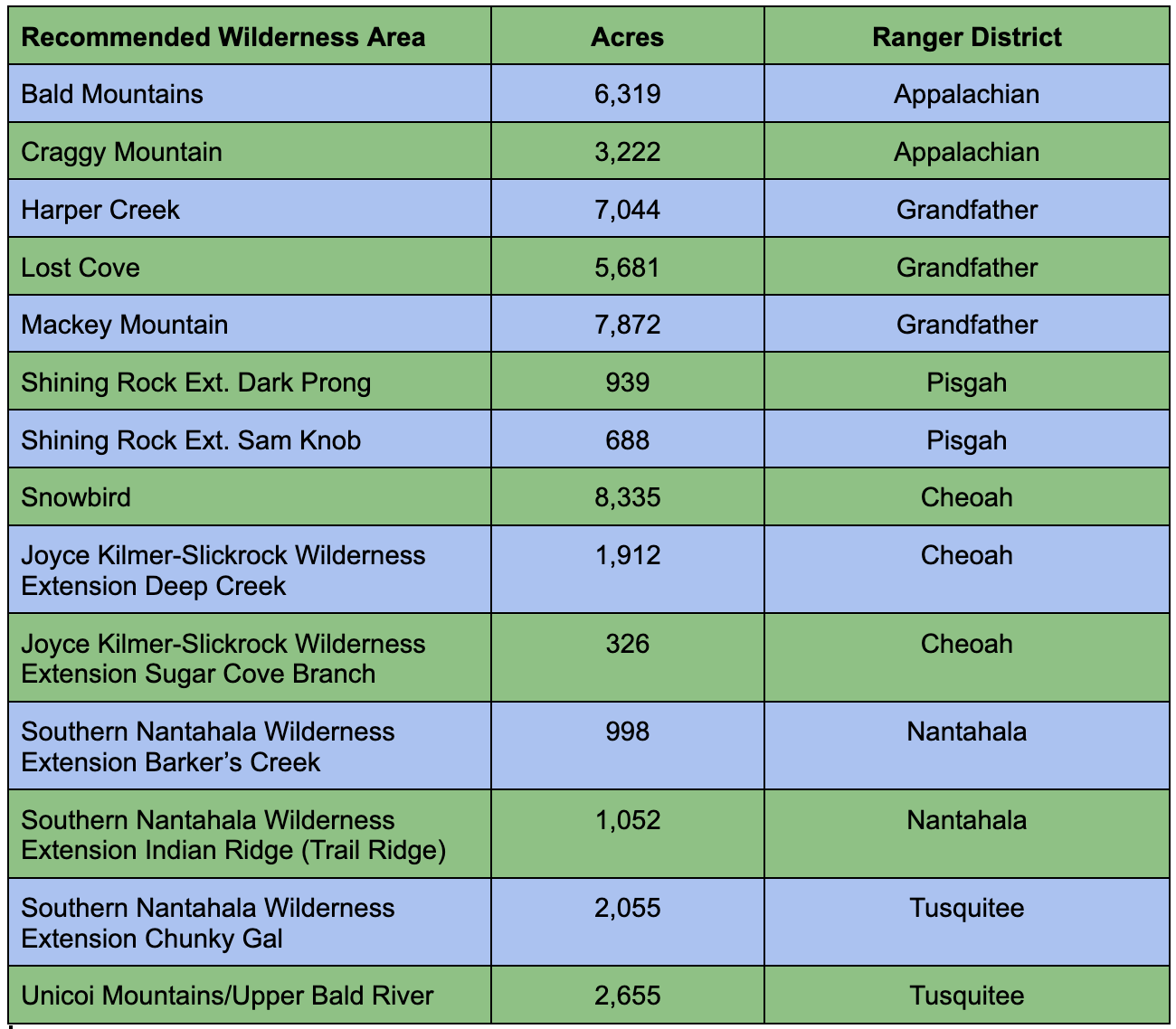

There are several categories of designation requiring an act of Congress that the Forest Plan addresses. The first is Wilderness recommendation. The designation of new Wilderness areas under the Wilderness Act of 1964 requires an act of Congress and the Signature of the President. The first step in that journey is the recommendation of suitable areas by the Forest Service during the forest planning process.

The Revised Plan allocates just over 49,000 acres in 14 areas to Recommended Wilderness. Compared to the current Forest Plan, that is an increase of 33,000 acres. While over 100,000 acres were both suitable and had collaborative support, the Revised Plan offers more for those that appreciate Wilderness than any time since the RARE II process of the late 1970s.

Despite being an improvement over the old plan, there are some curious omissions in the Revised Plan’s designations and some strange logic in those omissions. For example, the Black Mountains were disqualified because you can see sights and sounds of human development from the area, but Mackey Mountain was included despite I-40 being in the foreground view and very audible. A portion of the Chunky Gal is recommended for addition to Southern Nantahala Wilderness, but about 1,000 acres of the Inventoried Roadless Area was not recommended — again due to claims that sound from US Hwy 64 disqualified the area. The truth is that all of these areas are suitable for Wilderness recommendation, and the Forest Service should acknowledge that, regardless of whether they decide to recommend them for designation.

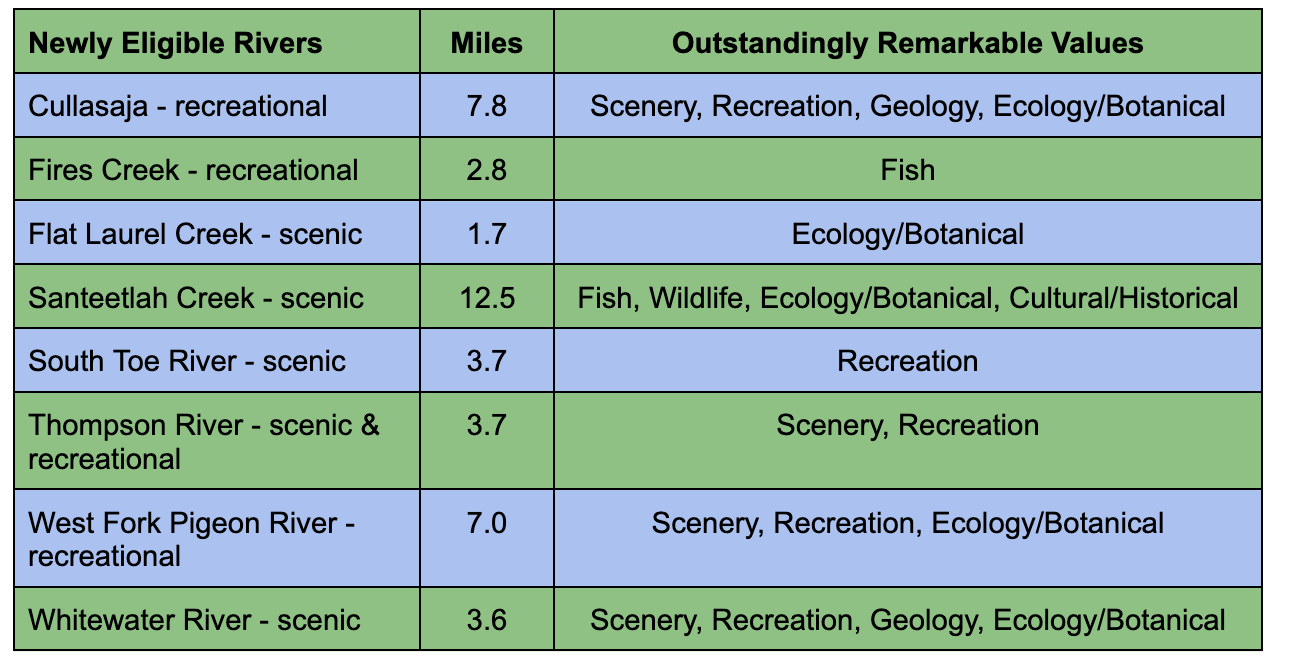

Wild & Scenic Rivers

The second major type of designation is the identification of streams eligible for protection under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The primary benefit of Wild and Scenic designation is to keep streams free-flowing and free of impoundments. There are three categories of Wild & Scenic Eligibility: recreational, scenic, and wild. Recreational is the least protective category, and Wild is the most protective. All three categories prevent eligible river segments from being impacted by dams once they are Congressionally designated.

The old plan recognizes 10 streams as eligible for Wild and Scenic designation, and the Revised Plan adds another 8 streams to that total. We were disappointed that the Forest Service did not find the North Fork of the French Broad, Panthertown Creek, and Greenland Creek eligible, and we believe the Forest Service should correct that error when the plan is finalized.

National Scenic Areas

The final designation opportunity in the Revised Plan is National Scenic Area (NSA) designation for the Craggy Mountains. This is perhaps the designation most likely to succeed in the next year because the people and government of Buncombe County support the protection of the area. Senators Burr and Tillis have indicated that they will not support federal designation without the endorsement of local governments. That box has been checked for the Craggy National Scenic Area.

The Forest Service has also designated over 10,000 acres of Big Ivy as a Forest Scenic Area. There is some ambiguity about the final boundaries of the Craggy NSA, as Buncombe County has endorsed a 15,000-acre area composed of all Forest Service Lands in the Craggy Mountains, while Forest Service has excluded Coxcombe Mountain, Snowball Mountain, Ox Creek, and Shope Creek from their recognition and placed them into areas where timber production is an emphasis. MountainTrue believes this should be corrected when the plan is finalized, and all these areas should be allocated to more protective management such as Ecological Interest Areas.

Sensitive Wildlife Could Be Impacted by Faulty Assumptions

The Revised Forest Plan has laudable goals for wildlife and wildlife habitat. The Plan emphasizes the creation of young forest and open woods for the wildlife that benefit from those conditions, and also includes strategies and standards for protecting more disturbance-sensitive species like green salamanders, bats, northern flying squirrels, and dozens of rare habitats that support an abundance of rare species.

The new plan aims to create more of this young forest through timber harvesting, but the top levels of allowable harvest, while being three to four times higher than current levels, are no higher than what is allowed in the old plan. As discussed above, we believe that the timber harvest goals will be counterproductive until the Forest Service has consistent direction regarding Natural Heritage Natural Areas, old-growth forests, and potential Wilderness Areas that are currently allocated to timber production. As far as strategies for increasing timber harvest, we fail to see how the Revised Plan is an improvement over the status quo.

Perhaps the biggest flaw in the plan content on wildlife is that the Final Environmental Impact Statement fails to show any benefits or costs to the management strategies and objectives in the Forest Plan. As a rhetorical question, why manage the forest for wildlife at all if there will be no benefits? We suspect that there will be costs and benefits for the management the Forest Service is proposing and that the Environmental Analysis is either too flawed or lacks the sensitivity needed to detect the changes that will occur. We also suspect that increased levels of young forest habitat would benefit associated species and cause declines in disturbance-sensitive species, but the Final Environmental Impact Statement shows neither trend. In general, we have serious concerns that the Forest Service is relying on flawed assumptions and inaccurate analysis for many of the decisions (and in some cases, the absence of a decision) in the Revised Forest Plan.

On the other side of the coin are dozens of rare species, many of them unique to this region, that the Forest Service analyzes with a coarse filter and without plan content to protect them. In particular, disturbance-sensitive species reliant on closed-canopy forest, old trees, and down wood are presumed by the Forest Service to be well protected by the 40% of the Forest that will remain lightly managed in this Forest Plan, again, partly due to faulty modeling, and partly due to not making assumptions from the models (for example, that old-growth forests will not be cut), management standards, or guidelines in the plan. So the Forest Service is assuming that old-growth forest-associated wildlife will not be impacted because the models assume no old growth will be cut. All the while, the Forest Service is asserting the right to cut old-growth forest in the plan.

The Forest Service should address these issues by improving their environmental analysis, and making the assumptions in their analysis translate into management strategies.

Recreation: Improvements to Trail Access but Too Restrictive to Other Activities

The Forest Service’s Revised Plan is an improvement over its own Draft Plan in terms of trail access. Two of the potential draft alternatives severely limited the potential to expand the existing trail network. Limiting opportunities for new trails would have been draconian considering the increasing demand for outdoor recreation, the already high use of Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests, and the social and economic benefits of outdoor recreation to our region.

The Revised Plan allows existing user-created trails and new construction to be added to the official trail system. However, the addition of any trails requires collaborative planning processes that consider supply and demand issues and have committed resources for long-term maintenance.

Overly restrictive limitations on other recreation resources — like rock climbing — lack the specificity needed to protect those resources and provide equitable public access. The Forest Service did not adopt Partnership’s suggestions regarding limitations on rock climbing as a recreation resource, nor is there a process for rock climbers or other recreationists to engage in collaborative management like there is for trail users.

The Forest Service should treat all user groups as potential partners and extend opportunities for collaborative management in the text of the plan to all interest groups.

Support Healthy, Resilient Forests

MountainTrue’s Public Lands Team tracks and analyzes every timber project in the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests to protect old-growth forests, sensitive habitats, and rare species. We help protect the places we share to ensure they stay healthy and beautiful for future generations. Support this work by making a donation to MountainTrue.