Taking Action on Timber Sales

From the very early days of its existence, a central focus of MountainTrue has been sustainable forest management on public lands, especially within Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests.

By Bob Gale, MountainTrue Ecologist and Public Lands Director

While much hard work was accomplished in getting the horrendous 1987 Forest Plan substantially amended in 1994, this did not alleviate all concerns over the U.S. Forest Service’s (USFS) management activities. Concerns repeatedly arose when timber sales were planned by various Ranger Districts within the two national forests. A few of these have been notable, and MountainTrue members and staff were often successful in getting the most controversial parts of these projects removed. The following are some examples:

Roaring Hole

The Roaring Hole Timber Sale was significant in that it was the first time USFS meaningfully responded to a Western North Carolina Alliance (WNCA) appeal of a timber project. WNCA volunteer and retired Silviculturist, Walton Smith (see Cut The Clearcutting), wanted to appeal the sale after an earlier appeal of the similar Little Laurel timber project had been denied. Smith wanted to strengthen this appeal by documenting on-the-ground information in the Roaring Hole project to show USFS the errors he saw in their project management. After consulting with Smith, WNCA Director Mary Kelly and her husband, Rob (who was an experienced professional forester), decided to hike into the timber sale stands to conduct the survey. In Mary’s words:

“We met Clarence Hall, a bear hunter from the Greens Creek Community of Jackson County who was concerned about the sale, at the beginning of a long, gated USFS road on an extremely frozen, shiny winter day — I about froze my ass off! We needed Clarence to guide us to the timber stands and also help us identify those tricky winter trees, since Rob and I were greenhorns in the WNC mountains. But before we could start our survey, Clarence informed us that we first had to rescue a couple of his neighbor’s lost bear dogs — one of which had been dragging a chain and was found stuck on a stump! With that unexpected task completed, Rob took forester’s prism plots to document stand characteristics for Walton’s premise that USFS was doing ‘cookie cutter’ clearcuts on very diverse kinds of stands and never considering alternative methods despite huge public concern. The information we gathered resulted in the first-ever remand of a USFS individual timber sale… it turned out NC National Forest Supervisor Bjorn Dahl, who was a silviculturist, agreed with Rob and Walton’s plot data showing stand diversity and the ‘cookie cutter’ problem. It was a momentous victory!”

Their success went beyond this timber sale. Supervisor Dahl had ordered a resurvey of the stands during the growing season (when plant diversity is most evident) and wanted research on alternate, non-clearcutting logging methods. Mary jumped at the chance to accompany the eminent USFS Southern Research Station scientist, David Loftis, on another visit to Roaring Hole. Loftis had been focusing on oak silviculture study because clearcuts were not resulting in the desired oak tree regeneration following such logging. He was also advising a Ph.D. candidate, Don McLeod — a Professor of Botany at Mars Hill College who, late in life was pursuing another degree, “Plant Communities of the Black Mountains” — documenting cove forest plant diversity. Their survey turned up an important plant ecosystem.

“Dave Loftis and I started wading through classic and significant cove vegetation up to our butts. We looked at each other and realized it simultaneously,” Mary remembers. “I called Dan Pittillo (Western Carolina University’s well-known Professor of Botany) and he informed me the proposed clearcut units were right on top of some sites he had forwarded to NC Natural Heritage Program as rare plant sites!”

By educating USFS about the diversity Mary and others had found at Roaring Fork and pushing for better project analysis, WNCA was successful in moving the agency toward change. Mary and WNCA’s legal advisor, Ron Wilson (who had also authored WNCA’s successful Appeal of the 1987 Forest Plan), used the field data in their next appeal — the Bee Tree Timber Sale in Transylvania County. USFS responded positively by improving its environmental impact assessments of proposed projects from what had been typically four-paged “no info-no problem” documents to those which included botanical surveys for the first time. The agency also hired its first staff botanist. These changes activated a new agency focus on the importance of rare plant species within WNC’s forest ecosystems — rare plants were previously largely ignored by USFS, and Mary recalls how one silviculturist referred to them as step-overs.

Bluff Mountain

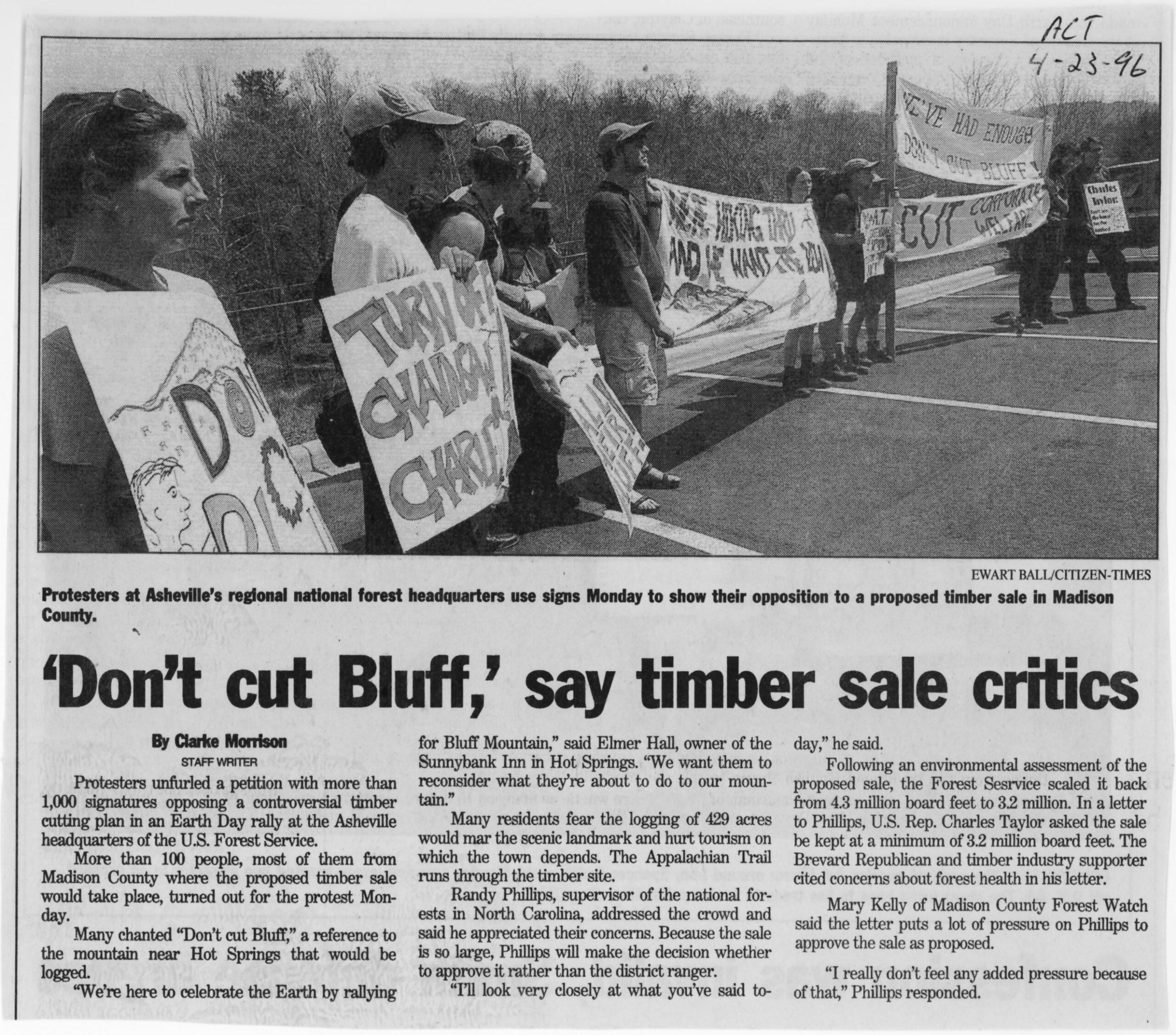

On the heels of the 1994 Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Management Plan Amendment victory (see Cut The Clearcutting), a backlash of dissatisfaction from some in the timber industry put pressure on USFS. Said pressure was the likely catalyst of the momentum behind the Bluff Mountain Timber Sale proposal.

The project called for 200 acres of logging and six miles of new roads carved over the biologically significant forests of Bluff Mountain and over the border into Tennessee’s Cherokee National Forest. Incredibly, it would also cross through the 400+ acre Fowler Tract, recently acquired by USFS for the specific purpose of protecting the Appalachian Trail. This was the biggest timber sale that USFS had ever proposed and the road mileage outraged the local Bluff community, including Hot Springs residents, bear hunters, tourism businesses, and raft companies. Many of these folks were also WNCA members.

WNCA didn’t initiate the Bluff Mountain campaign – it had recently lost some key forest staff and was also consumed with the highly controversial issue of extending I-26 through Madison County into Tennessee. However, many of its experienced members joined with others to fight the project using tactics they learned working within the Alliance. Elmer Hall, owner of the historic Sunnybank Inn and a Hot Springs WNCA member, notes that WNCA’s Director, Ron Lambe, “gave us all kinds of support, including widespread publicity about the negative aspects of the project through his close contacts in the news media.”

Ultimately, the campaign succeeded — the roads were not built and only about 20 acres of logging occurred. In addition, the coalition was able to get USFS to establish the Betty Place Trail in the former homestead site of that departed and much admired local resident.

Big Choga

In 1997, the Wayah Ranger District proposed a timber sale in the Valley River Mountains not far from Hayesville, which included the Big Choga Creek drainage. The sale attracted the attention of WNCA staff, its local members, and bear hunters for a singular reason. Big Choga was home to intact and documented old-growth forest communities (see Seeking Older Forests: WNCA’s Search For Treasure Trees), and WNCA was adamant about protecting WNC’s national forests. The bear hunting community was equally upset because old-growth trees — which are often hollow but nevertheless live on for many decades — were an important winter habitat for hibernating black bears.

WNCA’s Old-Growth Committee member and researcher, Rob Messick, had already made site visits to Big Choga and was in the later stages of data collection for the upcoming old-growth report. Messick continued to make site visits throughout the sale process. Because he and his assistants had identified numerous old-growth trees and mostly undisturbed habitat, WNCA determinedly appealed the project’s Final Decision, which called for logging in these communities.

While this was going on, an amazing story had been unfolding that grabbed national attention. During the Atlanta 1996 summer Olympics, a backpack bomb had been found in Centennial Olympic Park by a police officer. He managed to evacuate much of the crowd before the bomb exploded, but two people ultimately died and 111 were injured. The bomb was traced to one Eric Rudolph, who had been active in the pro-life movement and who happened to have grown up in the WNC mountains. After the Atlanta attack, Rudolph went on the run and was a most-wanted fugitive.

It was highly publicized that Rudolf had excellent wilderness survival skills. Media reports claimed he could live off the land indefinitely, intimately knew the WNC mountain topography, and had many hiding spots there. Rudolf’s truck was found abandoned at a campground very near the Big Choga area. Local police and the FBI began a manhunt, searching the area’s forests and coincidentally encountering Messick’s old-growth researchers during their site visits. They were allowed to continue collecting old-growth data, but the encounters and news stories added a surreal experience to their research. The myth of Rudolph’s wilderness survival capabilities was eventually dispelled when the fugitive was found raiding a dumpster in Murphy, NC.

WNCA Executive Coordinator Brownie Newman requested a Big Choga timber sale site visit with the Wayah District, which was granted, and then worked with WNCA’s local Tusquittee Chapter Chair, Aurelia Stone, to turn out members for the visit. A long line of cars was given access through the gated road to the Big Choga sale and throughout the day, these volunteers and staff made their case to the District Ranger and his resource staff. During a break within a contested timber stand, a major discussion ensued and at one notable point, the Ranger asked his Botanist, “Do you think this is an old-growth forest?” His Botanist replied, “Well — Yes, I do.” After the visit, Newman gathered with the WNCA group and they collectively agreed to a bottom line of which points could be retained and dropped in order to settle the Appeal. It was unanimous that the old-growth stands must be dropped.

In the subsequent Informal Disposition meeting in Franklin, NC, Brownie could not convince the District Ranger to leave out the old-growth, so he stated that WNCA would not drop its Appeal. As he turned to walk out, the Ranger suddenly called him back. He started adjusting lines on the sale proposal map with his pen, removing nearly all of the old-growth areas. In the end, a consensus was reached and the Appeal was dropped. It was the first time this Ranger had ever agreed to WNCA terms on a project.

Big Choga had a lasting impact in establishing a precedent. Citing this milestone agreement in his written comments and negotiations with other ranger districts, WNCA Ecologist Bob Gale and members of the WNCA Forest Task Force were able to convince USFS to avoid old-growth in later timber projects. Soon after Big Choga, Rob Messick’s landmark report, Old Growth Communities in the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest (Messick, May 2000), was published by WNCA, giving the organization even more leverage in championing old-growth protection in Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests.