Seeking Older Forests: WNCA’s Search For Treasure Trees

Seeking Older Forests: WNCA’s Search For Treasure Trees

Thanks to the efforts of Rob Messick and Josh Kelly, the decades-long focus on old-growth forest protection continues as a primary goal of WNCA/MountainTrue to this day.

By Bob Gale, MountainTrue Ecologist and Public Lands Director

In the early 1990s, old-growth tree expert Bob Leverett and some of his colleagues started researching old-growth forests in Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP). About one-third of the Smokies had never been logged, so the area offered a glimpse of what Southern Appalachian old-growth forests looked like before their destruction by European colonizers, later industrial logging, and U.S. Forest Service management.

Edward Yost, Katherine Johnson, and William Blozan were hired to work as a team in GSMNP from 1993-1994. The team assessed forests containing old oak and eastern hemlock in anticipation of the arrival of invasive insect species, like the gypsy moth and the hemlock woolly adelgid. Their study established protocols that became helpful in locating remnant old-growth communities beyond GSMNP. Other work was beginning in this area, as well. Forester Paul Carlson and Clemson Emeritus Professor of Forestry, Bob Zahner, were documenting old-growth in the mountains in the Chattooga River Watershed. Alan Smith, Professor of Biology at Mars Hill College, had also identified old-growth in the Walker Cove Research Natural Area within Pisgah National Forest. Smith later conducted an initial old-growth assessment in the greater Big Ivy area.

Early Western North Carolina Alliance (WNCA) member Rob Messick volunteered in Bob Leverett’s on-the-ground GSMNP studies and apprenticed with the GSMNP Old-Growth Team. At that time, the Forest Service was hesitant to believe that much old-growth remained in WNC’s Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. But Leverett was confident that more old-growth stands still existed, and Messick and others became intrigued with the idea and wanted to search for them.

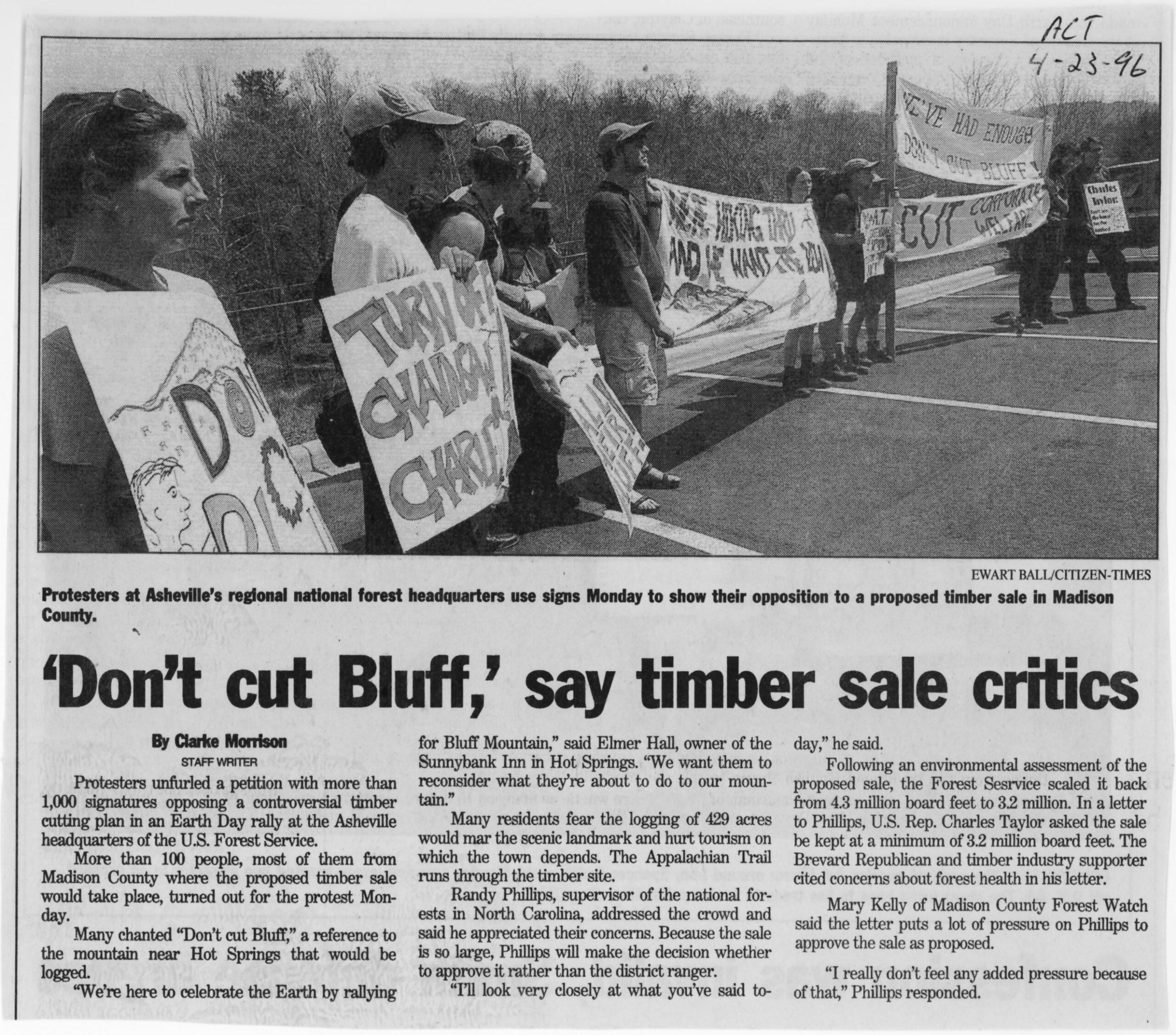

The regional studies of Leverett and others interested WNCA. A dedicated group, including Leverett, Zahner, Carlson, Messick, UNC-Asheville’s Gary Miller, and former Forest Service botanist Karen Heiman, joined WNCA Director Mary Kelly to stage the first Eastern Old-Growth Conference at UNC-Asheville in 1993. Its purpose was to raise awareness and elevate the importance of these forest communities and push for their protection in WNC’s national forests. Seventy-five conference attendees drafted and signed a resolution to exclude confirmed old-growth from timber sale proposals in eastern national forests.

Simultaneous with the planning of the conference, the Walker Cove Research Natural Area was being targeted for logging. A groundswell of concern, headed by Karin Heiman, was growing to protect Walker Cove and Big Ivy. Her effort received strong support from Brock Evans, a nationally prominent forest activist of the Western Ancient Forest Campaign. Mary Kelly notes:

“Evans urged the above group to use the name ‘Big Ivy’ and make it stick! Brock was an old DC lobbying hand and a firm believer of ‘Name it and Save it’ from his work to save South Carolina’s Congaree Swamp* and countless other rare places across the US. Evans even got North Carolina U.S. Representative Charlie Rose to write a congressional letter to save Big Ivy, which I believe caused the Forest Service to take the area out of the timber base for years.”

The conference created the momentum for one of WNCA’s most notable programs. Kelly used a Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation grant to initiate WNCA’s Seeking Older Forests, Finding Common Ground campaign. This title, which Mary coined, perfectly reflected the organization’s advocacy through the community outreach precedent established by its founders, Esther Cunningham and David Liden (see Grassroots and Tree Roots: WNCA’s Beginnings). The campaign involved three essential steps:

Step one: Consult the Forest Service’s stand-oriented databases and review the identified old-growth stands in North Carolina Natural Heritage Program sites.

Step two: Interview local family members, hikers, hunters, birders, and others about areas they felt had never been logged or were still relatively intact, and compile research of relevant land acquisition records for the national forests.

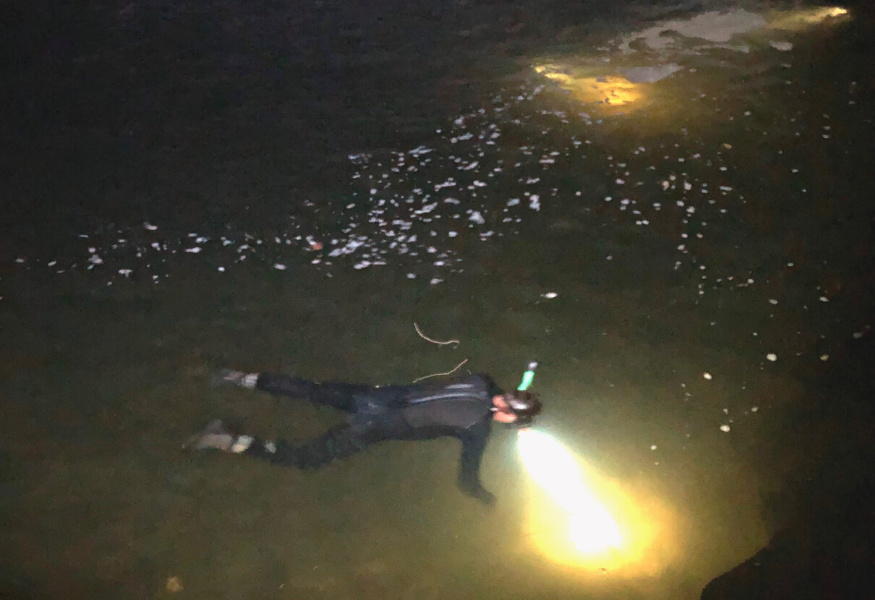

Step three: Use the information gained in steps one and two to identify the most likely locations of WNC’s remaining old-growth and visit these targeted sites to collect on-the-ground data, an activity known as ground-truthing. The purpose of this ground-truthing was to establish what old-growth forests actually remained. It included many hours of car travel, finding overnight accommodations or campsites, and long, steep hikes to remote sites with difficult access.

Rob Messick became the driving force of this research, gathering and compiling it into an inventory of old-growth community locations, tree sizes, and ages. To help accomplish this, he made solo trips and took small teams of assistants to numerous targeted sites throughout the two national forests. Site visits involved braving uncertain weather conditions, steep terrain, biting/stinging insects, and occasionally spiders. Messick and crew successfully avoided venomous snakes, but minor bodily injuries from their challenging work were frequent. However, Messick persisted and employed his skills as a master organizer of extensive and detailed information.

In May 2000, after seven years of work involving 500 site visits, 50 volunteers, and hours of writing, Messick produced the landmark report, Old-Growth Forest Communities in the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest. An astonishing 77,418 acres of old-growth forest were located and delineated in WNC, dispelling the myth that old-growth was restricted to only a few well-known sites. The report was widely publicized by newspapers as local as the Asheville Citizen-Times and as far away as the Boston Globe. Numerous editorials of such newspapers endorsed the idea of protecting existing old-growth forests in national forests.

WNCA’s funding for the campaign ended with Messick’s report, but further important old-growth surveys were continued in the mountain forests of North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Virginia by other researchers. One of these researchers was a rising young botanist named Josh Kelly, who conducted surveys for the Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition and the environmentally-focused Wildlaw legal firm. In 2011, Kelly became MountainTrue’s Public Lands Field Biologist and has since worked diligently to protect old-growth from Forest Service timber project proposals.

*Note: While living in South Carolina in the 1970s, MountainTrue Ecologist and Public Lands Director Bob Gale was a part of the successful campaign to protect Congaree Swamp’s old-growth trees. He worked with local activists to push their Congressional Representative to introduce a bill for the 17,500-acre “Congaree Swamp National Monument.” The tract was known by foresters as the “Redwoods of the East” and contained many trees ranked as national champions. Signed into law in 1978 by President Gerald Ford, the tract was eventually expanded into the current 27,000-acre Congaree National Park.