MountainTrue’s Analysis of Henderson County’s Draft Comprehensive Plan

MountainTrue’s Analysis of Henderson County’s Draft Comprehensive Plan

Update: We have added detailed analysis and recommendations to improve the Comprehensive Plan further down on this page. We are providing these recommendations to the Planning Board and Henderson County Commissioners. Scroll down to view.

On September 9, 2022, Henderson County released the first draft of the 2045 Henderson County Comprehensive Plan. You can view a virtual presentation about the draft plan here. MountainTrue is conducting a full analysis of the draft plan and will provide a detailed set of recommendations to the Henderson County Planning Board and County Commissioners to ensure that the plan addresses the priorities of county residents as reflected in the county’s own survey*.

The draft plan will guide Henderson County’s growth and services for the next 20 years. Overall, the draft plan includes a strong set of goals that MountainTrue fully supports. Those goals, found on p.34 of the draft plan, include:

- Coordinate development near existing community centers.

- Protect and conserve rural character and agriculture.

- Improve resiliency of the natural and built environments.

- Prioritize multi-modal transportation options and connectivity.

- Create a reliable, connected utility and communication network.

- Stimulate innovative economic development initiatives, entrepreneurship, and local businesses.

- Diversify housing choices and availability.

- Promote healthy living, public safety, and access to education.

These goals provide a solid foundation for a 20-year plan. MountainTrue’s recommendations below offer targeted strategies to help the county achieve these goals. We start, however, with one glaring omission in the draft plan.

Primary Recommendations

Include a Detailed Implementation Plan

The County Commission’s adoption of the comprehensive plan is just the first step towards realizing the goals within. The real challenge comes in translating the plan’s strategies into the day-to-day operations and actions of the government, and in making the plan work in concert with the County’s other strategic actions and policy documents. To date, the draft plan and recently released draft appendix do not include any guidance for implementing the plan’s recommendations.

The 2020 Comprehensive Plan, adopted in 2004, is widely considered a success, as the county has accomplished a majority of the plan’s goals. This was no accident. That plan contained a detailed implementation schedule that held our county leaders accountable while allowing the public to track our progress. Henderson County needs to draw on this past success to ensure that the 2045 plan accomplishes its goals rather than gathering dust on a shelf.

We strongly recommend developing a process to implement the plan’s priority strategies and track plan progress. Various ways to ensure the implementation of the plan include:

- Establish a single point of contact who will oversee the plan’s implementation. This will ensure accountability and continuity in the years that follow adoption.

- Form a county team with representatives from key departments who will meet to track the plan’s progress, develop action items to implement strategies, educate staff about the plan’s goals, and help shape departmental work plans around the Comprehensive Plan.

- Review plan progress with applicable boards and commissions and recommend new priorities to the County Commission.

- Conduct an annual report on progress of the plan to the County Commission and set priorities.

- Evaluate the viability of the plan every three to five years, and update the plan accordingly.

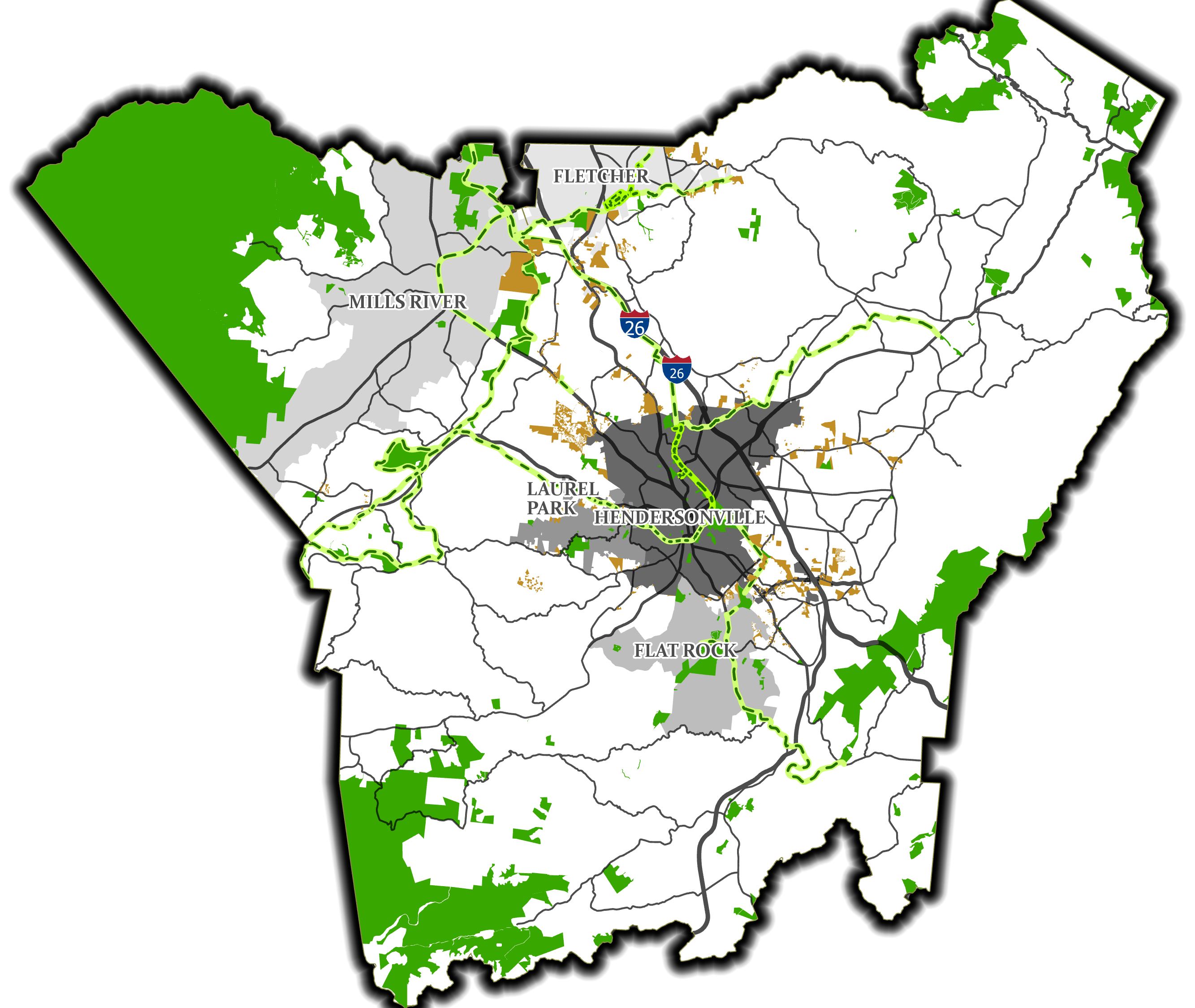

Don’t Expand the Utility Service Area

We encourage the City of Hendersonville and the County to share in decision-making around where sewer services will go. The county should have representation on the City’s water and sewer governing bodies, have a say in where the pipes extend throughout the county, and whether annexation follows those pipes. Therefore, the county must work closely with municipalities to direct new growth where infrastructure already exists.

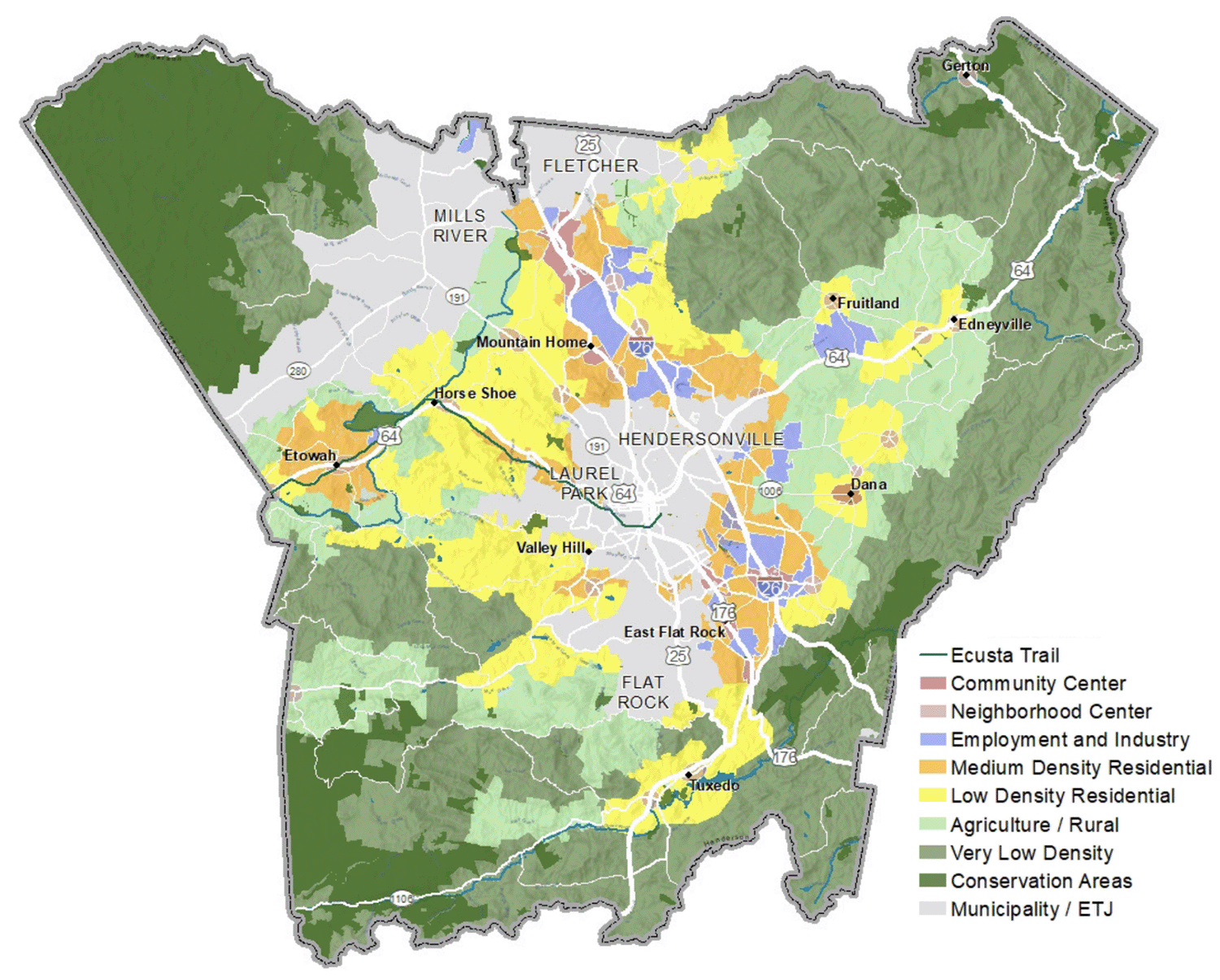

Expanding the Utility Service Area (USA) to include Edneyville and Etowah will only encourage the development of new sewer that exceeds the current needs of these communities. This is a recipe for suburban sprawl all along the US 64 corridor. We do not support the current draft Future Land Use Map calling for commercial shopping centers and dense infill development in Edneyville or Etowah, as the existing infrastructure in these communities cannot support such development. We recommend maintaining the Central USA, as presented in the 2020 Henderson Comprehensive Plan.

We do not support the residential density described in Infill Area (formerly Medium Density Residential) designations in the more rural areas of the county outside the Central USA, including Etowah and Edneyville’s proposed USAs. The density allowed within Infill Areas (8-14 units/acre) would likely require new sewer service or package plants, spurring additional suburban sprawl to areas of the county lacking the infrastructure and road networks to absorb such volume.

We also do not support the amended density allowances in the new Transitional Area (formerly Low Density Residential) designation, as this will drive suburban sprawl into the Tuxedo, Dana, and Gerton communities — all found well outside the Central USA. Allowing for developments as dense as quarter-acre lots would tax our existing roads and alter the rural character of these communities.

Address Water Quality Concerns in Edneyville and Etowah

Wastewater seriously impacts water quality, and the county should invest wisely in wastewater infrastructure. We strongly encourage Henderson County to address water quality concerns in Edneyville and Etowah without inviting suburban sprawl into these communities.

Edneyville: Adding another municipal sewage treatment plant in the Mud Creek watershed may contribute to water quality concerns. Edneyville’s existing uses (Edneyville Elementary, the Training Academy, Camp Judaea, etc.) should tie into the city’s existing sewage treatment system, and the city should refrain from annexing these rural areas, as they lie outside the Central USA.

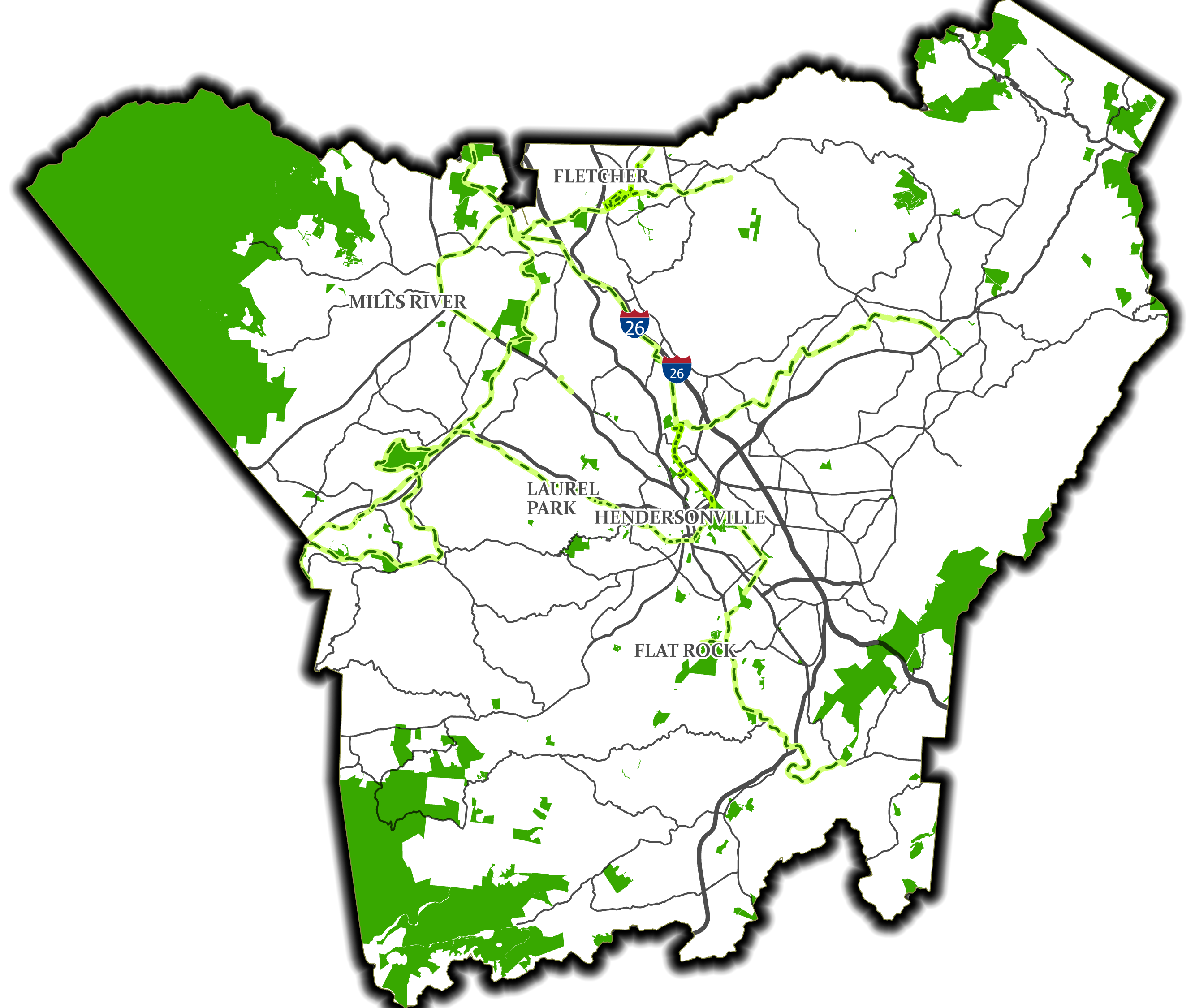

Etowah: It is foreseeable that Etowah’s aging private sewer system may one day be acquired by the Metropolitan Sewer District, given its proximity to MSD’s existing network. By connecting Etowah to MSD’s system, Etowah’s capacity for development could significantly increase in the next 20 years. With the highly anticipated construction of the Ecusta Trail about to begin, we must take measures to preserve the trail’s rural character that makes it such an attractive destination.

Additionally, any expansion of sewer infrastructure should be constructed with limited capacity to service only existing businesses and residences without facilitating future growth. The county should implement strong land use protections to prevent sprawling and high-density residential development, high-intensity and industrial uses, and other uses outside of the Central USA that compromise the rural character and agricultural heritage of the area.

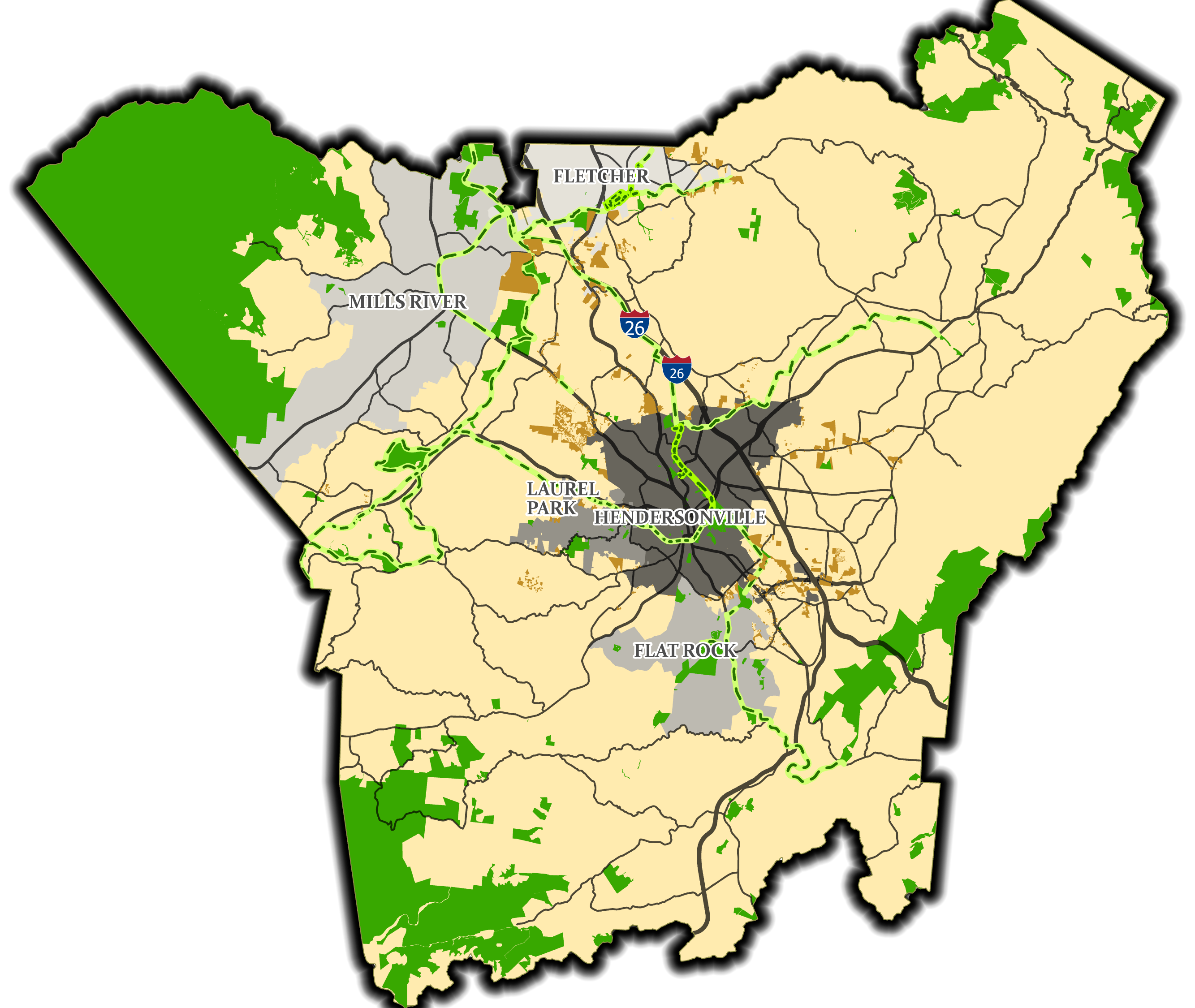

Provide More Housing Options in the Central Utility Service Area

When people think of housing choice, they usually default to single-family homes or large apartment complexes. But we are missing the opportunity to provide new homebuyers and renters a wide array of housing choices, many that are more affordable than what the current market provides.

To offer more housing choice in the areas that can best support it – the Central Utility Service Area – we recommend broadening the types of housing that can be developed in traditional single-family neighborhoods. Remove restrictive zoning that stands in the way of modest infill development, like duplexes, triplexes, and townhouses. Within the Central USA, we recommend amending the Infill Area zoning designations to include ADUs, townhouses, duplexes, and triplexes. We also support the new density allowances for Transitional Areas within the Central USA, as this housing would be located closer to the services, jobs and infrastructure already concentrated in our municipalities.

Adopt a Voluntary Land Conservation Fund

We fully support the development of a fund that focuses on preserving working farmland and parcels key to greenway, park, and recreational opportunities, and sensitive natural areas. Consider a bond referendum to establish the fund. Focus on the Purchase of Development Rights to preserve working farms and make them more affordable to new farmers. Consider easements that would improve water quality protection.

Consolidate and Strengthen Steep Slope Controls

Current steep slope regulations are found scattered throughout the Land Development Code, making it difficult to assess their impact on ensuring public safety, protecting water quality, and preserving scenic mountain views. Residents and developers would be better served if the steep slope controls were consolidated, transparent, and more concise. We applaud the Planning Board’s recent efforts to address this, and we encourage the county to include such improvements in the draft plan.

*The county has published a second public input survey. Click here to take the new survey.

Additional Recommendations & Further Details

In addition to our primary recommendations, MountainTrue makes the following suggestions specific to various recommendations found in the draft plan:

FUTURE LAND USE MAP (pp.38-44)

MountainTrue: We question whether the Dana community can support the recommended Industrial & Employment land use designation without sewer service.

GOAL 2: PROTECT AND CONSERVE RURAL CHARACTER AND AGRICULTURE

R. 2.1.E. (p.57): Encouraging small businesses in rural areas can indirectly support agriculture by allowing non-farm income.

MountainTrue: To encourage appropriate small business development and maintain the rural and agricultural character of these areas, we recommend limiting the square footage of new structures and specifically defining what small-business activities are preferred in Agriculture / Rural Districts.

Rec 2.2.B. (p.58): Create a Voluntary Farmland Preservation Program to purchase farmland development rights and establish agricultural conservation easements.

MountainTrue: We recommend amending the Land Development Code to require that eligible applicants meet specific environmental standards or implement appropriate “best management practices” that protect water quality, such as undisturbed stream buffers.

Rec. 2.2.C. (p.58): Study potential mechanisms for private transfer of development rights program to allow for the transfer of density away from agricultural and natural resource areas to designated receiving areas.

MountainTrue: We strongly support the county in investigating a potential transfer of development rights program and would be willing to advocate for state authorization to provide Henderson County with this valuable conservation tool.

Rec. 2.3.C. (p.58) Consider zoning updates to reduce development pressure in agricultural areas.

MountainTrue: We recommend exploring new incentives to give farmers multiple options to preserve the working lands. We do not support the concept of downzoning Agricultural / Rural districts, such as requiring five-acre lot minimums, as this will only accelerate the development of undisturbed areas, while serving the few that can afford to purchase larger lots.

Rec. 2.4.A. (p.59): Provide incentives for revitalizing existing commercial and industrial sites.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and encourage the Commission to prioritize commercial and industrial sites closest to main transportation corridors and in areas already serviced by existing water and sewer to disincentivize sprawl.

Rec. 2.4.B. (p.59): Focus on higher-density housing closer to the city to reduce sprawl, provide affordable housing for the workforce, and relieve pressure on roads.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this designation, but we also recognize this requires coordination with municipalities, including participation in Hendersonville’s upcoming comp planning process. We encourage County staff and leadership to engage Hendersonville in developing plans that focus higher density development in appropriate areas already served by sewer and water, located closest to job and commercial centers, schools, and services.

Rec. 2.4.C. (p.59): Encourage industrial growth in areas away from large concentrations of farmland and agricultural operations.

MountainTrue: We question whether industrial uses and agricultural operations are mutually exclusive. Given the low residential density in such districts, there may be opportunities to cite appropriate industrial uses near working farmland, concentrating such activities away from established residential areas.

Rec. 2.4.D. (p.59): Carefully evaluate potential utility extensions that could impact large concentrations of productive farmland.

MountainTrue: See our Primary Recommendations above re: Edneyville and Etowah sewer expansion.

GOAL 3: IMPROVE RESILIENCY OF THE NATURAL AND BUILT ENVIRONMENTS

GOAL 3 (p.60): Where risk reduction is not possible, careful planning and strengthening emergency response will help make recovery faster and more efficient when hazards do occur.

MountainTrue: We recommend: “Where risk reduction is not possible, careful planning could mitigate the impact of extreme events, thus reducing the costs of recovery for both private and public funds. Similarly, strengthening emergency response will save taxpayer dollars…”

Rec. 3.1.C. (p.60): Consider allowing for administrative approval for conservation subdivisions that meet certain criteria (i.e. are under a density threshold, have a minimum amount of open space, reserve priority open space types, and meet access standards).

MountainTrue: While we support this concept, we’ll note that administrative approval for conservation subdivisions works only if the thresholds are well defined. We recommend examining existing regulations and streamlining the project permitting and approval process so that development decisions are more timely, cost-effective, and predictable for the community and home builders.

Rec. 3.1.E. (p.61): Limit development on steep slopes and mountain ridges.

Rec. 3.3.C. (p.63): Discourage the amount of land disturbed in steep slope developments, including construction of roads, as well as decrease density.

MountainTrue: We strongly support these recommendations and would be willing to provide model ordinances from similar communities that have addressed steep slope development.

Rec. 3.3.D. (p.63): Continue to limit fill in floodplains unless additional standards are met.

MountainTrue: Under this recommendation, the County could further restrict the use of floodplains. Consider that multiple scientific studies now show that 100-year floods are increasing in frequency, including a Yale Environment study that predicts that Southeast counties like Henderson could experience such floods every one to 30 years.

Rec. 3.3.G. (p.64): Adopt best practice design standards for new construction within the wildland/urban interface.

MountainTrue: While we agree with this recommendation in concept, we seek clarification of the definition of “wildland/urban interface,” as the Future Land Use Map makes no reference to such designation.

Rec. 3.4.E. (p.64): Educate the community and developers regarding green infrastructure projects, as well as state and federal rebates and tax incentives, which can lessen stress on natural systems.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this, and encourage the County to consider expanding streamside buffers to protect water quality.

GOAL 4: PRIORITIZE MULTI-MODAL TRANSPORTATION OPTIONS AND CONNECTIVITY

Rec. 4.1.C. Advocate for the French Broad River MPO (Metropolitan Planning Organization) to update the Comprehensive Transportation Plan, which was adopted in 2008, and focus improvements around active transportation options and transit.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and ask the County to consider extending transit services to employment and commercial centers beyond the Central Utility Service Area.

Rec. 4.2.B. (p.68): Consider reducing Henderson County’s Traffic Impact Study (TIS) threshold for developments located along specific road classifications.

MountainTrue: We support a reduction in traffic study thresholds in conservation/rural/ag-zoned areas, and recommend increasing the threshold for traffic studies in areas appropriate for denser development.

Rec. 4.2.D. (p.68): Consider amending the Land Development Code to allow for the integration of residential and commercial uses to allow for shorter travel time between destinations.

MountainTrue: Mixed-use developments are beneficial to combating sprawl, but the plan needs to specify where mixed-use would be deemed appropriate. Community centers and neighborhood anchors appear to be the most appropriate locations for mixed-use development. There will need to be adequate infrastructure already in place to support this level of development.

Rec. 4.3.A. (p.68): County staff should continue to seek grant funding (through the French Broad River MPO and other sources) for corridor studies along primary roadways throughout the county.

MountainTrue: We fully support commissioning a study of the Ecusta Trail corridor to inform appropriate land use designations along its path.

Rec. 4.3.B. (p.68): Establish a vision for significant roadway corridors and their surrounding land use, with input from the community they serve.

MountainTrue: This visioning process can be folded into an updated small-area planning process for Edneyville and Etowah. We would be willing to assist with gathering public input to inform these plans.

Rec. 4.3.D. (p.68): Support NCDOT with the ongoing corridor studies for US-64.

MountainTrue: This corridor study must consider future land-use recommendations for Edneyville and Etowah. We believe that an inappropriate expansion of sewer service in these communities will increase congestion along US 64 and contribute to suburban sprawl and loss of working farmlands.

Rec. 4.4.C. (p.69): Conduct studies of the transportation network surrounding County schools to identify deficiencies in safety and access.

MountainTrue: There is a critical need to address Etowah Elementary School and Etowah Park. We recommend investigating the Safe Routes to School program. We also recommend the County commission a bike/pedestrian connectivity study.

Rec. 4.5.C. (p.69): Initiate a study of Apple Country Public Transit to identify whether fare rates are a barrier to the use of the bus system and study the feasibility of a fare-free system.

MountainTrue: We support this and encourage the County to investigate the benefits of a fare-free system.

Rec. 4.5.G. (p.70): Explore mechanisms to provide express routes to connect Hendersonville to Asheville and other destinations in Buncombe, Madison, and Haywood County, while focusing on regional mobility management, employee training, maintenance, and funding administration.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and recommend advocating for transit connections to employment centers in Buncombe, Madison and Haywood counties to reduce traffic congestion along the primary north-south transportation corridors like I-26, US 25, and NC 191. We encourage the County to coordinate the comprehensive planning process with the ongoing planning process in Buncombe County.

Rec. 4.5.H. (p.70): Create connections between transit and greenways to help reduce traffic, vehicle miles traveled, and the county’s carbon footprint.

Rec 4.7.E. (p.71): Coordinate with the Rail Trail Advisory Committee, Transportation Advisory Committee (TAC), Planning Board, and Recreation Advisory Board on priority greenway implementation.

MountainTrue: We strongly support these recommendations and suggest hiring a sustainability coordinator to lead this important work.

Greenway and Sidewalks Map (p.73)

MountainTrue: Add language/graphics denoting the future regional Hellbender Trail and potential connections.

GOAL 5: CREATE A RELIABLE, CONNECTED UTILITY AND COMMUNICATION NETWORK.

Rec. 5.3.C. (p.75): Require conservation subdivision designs for all new major residential subdivisions residential growth in unincorporated areas tied to sewer infrastructure.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and can provide Best Management Practices and precedent for sound conservation subdivision designs.

Rec. 5.4 (p.75): Take a leadership role in sewer and water planning by helping to foster intergovernmental cooperation.

MountainTrue: As stated in our Primary Recommendation, we fully support the County and Hendersonville to work together to address sewer expansion that does not promote suburban sprawl, while addressing current water quality concerns.

Rec. 5.4.B. (p.75): Conduct interchange studies with the City to evaluate and prioritize the development potential of key interchanges for future commercial and/ or industrial development.

MountainTrue: We strongly support collaborating with the City to coordinate development with existing sewer and water services.

Rec. 5.4.C. (p.75): Begin the development of a three, five, or ten-year capital improvement program and capital reserve fund to help implement planned investments in sewer infrastructure and other services.

MountainTrue: This requires coordination with MSD’s Capital Improvement Program and Hendersonville’s sewer & water services. We strongly encourage the County and City to work together on this.

Rec. 5.4.D. (p.75): The Environmental Health Department should identify areas of septic failure, areas where future septic systems may fail, and address these through existing remediation programs and by leveraging state and federal grants.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and will work with our Legislative Team to advocate for adequate state funding.

GOAL 6: STIMULATE INNOVATIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVES, ENTREPRENEURSHIP, AND LOCAL BUSINESSES

MountainTrue: Add “conservation and outdoor recreation, bike/ped/transit” to initiatives, as they will bring in the kind of businesses the community desires.

Rec. 6.4 (p.79): Facilitate placemaking efforts to reinforce community character and attract businesses and investment.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and would be willing to assist in community engagement around such placemaking efforts.

GOAL 7: DIVERSIFY HOUSING CHOICES AND AVAILABILITY

Rec. 7.1.B. (p.80): To avoid conflict with agricultural areas and natural resources, major subdivisions should be located near defined centers and within Medium and Low Density Residential areas as defined on the Future Land Use Map.

MountainTrue: Discourage rezonings for higher-density residential subdivisions outside the defined Utility Service Area and within the Agricultural/Rural districts identified on the Future Land Use Map.

Rec. 7.1.C. (p.80): Allow for a variety of housing types, including condos, townhomes, and multi-family complexes, in the defined Urban Service Area.

MountainTrue: We strongly support this and recommend that “missing middle” developments, including Accessory Dwelling Units, townhouses, duplexes, and triplexes, be allowed by right in Medium Density Residential districts.

Rec. 7.2.E. (p.81): Continue to allow for manufactured homes in designated zoning districts in the county.

MountainTrue: Consider allowing manufactured homes by right in all residential districts. They represent the last option for truly affordable housing in the region.

Rec. 7.3 (p/82): Support the ability to “age in place.”

MountainTrue: Include language encouraging the implementation of Universal Design best practices that create homes that are accessible and habitable for all ages and abilities.

GOAL 8:PROMOTE HEALTHY LIVING, PUBLIC SAFETY, AND ACCESS TO EDUCATION

Rec. 8.1.B. (p.84): Address facilities and programming priorities, document ongoing maintenance needs, and provide benchmarking related to facilities and staffing within a master plan.

Rec. 8.1.E. (p.84): Develop a master plan for Jackson Park. The master plan should address connectivity, parking issues, and facility enhancements, and involve a variety of user groups.

MountainTrue: Jackson Park is already at capacity for hosting recreational events. We recommend expanding master planning efforts to encompass all county park facilities.

Rec. 8.1.L. (p.85): Require major subdivisions to provide pedestrian connections or provide easements to immediately adjacent greenway facilities.

MountainTrue: We support establishing concurrent sewer/trail easements where sewer expansion is permitted.

Rec. 8.3. (p.86): Expand healthy food access.

MountainTrue: Add “F. Continue support for a food waste program.”