Testing by MountainTrue shows that microplastics are present throughout the Broad, French Broad, Green, Hiwassee, Little Tennessee, New River and Watauga River Basins.

Western North Carolina — Regional conservation organization MountainTrue has documented the high levels of microplastics in surface water samples collected from waterways throughout western North Carolina. Microplastics are pieces of plastic smaller than 5 millimeters that are the result of the breakdown of larger plastic litter and debris into smaller and smaller pieces. They are harmful to aquatic life and are considered a potential threat to human health.

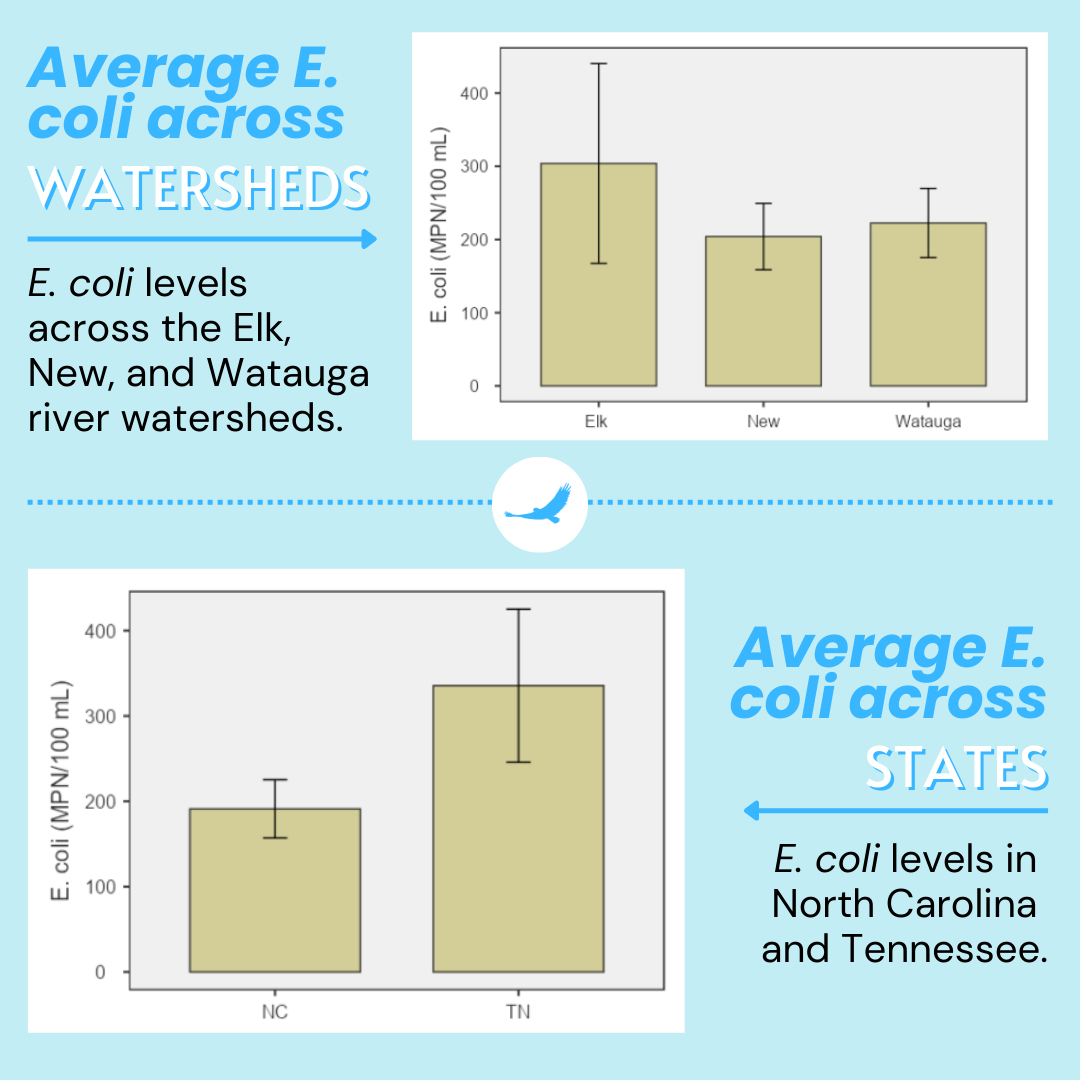

MountainTrue collected and analyzed water samples from the Broad, French Broad, Green, Hiwassee, Little Tennessee, New River and Watauga River Basins. We found microplastics in every sample from every region, even in otherwise pristine areas and protected watersheds. We documented an average of 19 particles of microplastic per liter of water across all tested watersheds. The highest particle counts of microplastics were found in the Little Tennessee (37 particles/liter) and Hiwassee (30 particles/liter) watersheds. Even in watersheds with lower levels of microplastic contamination, there were testing sites with concentrations in the high twenties and thirties.

|

Watershed

|

Avg no. of microfibers per liter

|

Avg no of microbeads per liter

|

Avg. no of microfragments per liters

|

Avg. no. of microfilms per liter

|

Avg no. of all microplastics per liter

|

|

Broad River

|

12

|

1

|

5

|

6

|

24

|

|

French Broad River

|

7

|

0

|

4

|

5

|

16

|

|

Green River

|

20

|

0

|

5

|

2

|

27

|

|

Hiwassee River

|

18

|

0

|

2

|

10

|

30

|

|

Little Tennessee River

|

29

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

37

|

|

New River

|

20

|

0

|

3

|

6

|

29

|

|

Watauga River

|

14

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

17

|

|

All Watersheds

|

12

|

0

|

2

|

5

|

19

|

Microfibers, which come from synthetic clothing and fishing line, was the most common form of microplastic that we observed. Microfilms, which degrade from plastic bags and food wrappers, accounted for more than a quarter of microplastics recorded.

There have been significant amounts of microplastics research in marine systems, but microplastics in freshwater systems have been less studied overall. MountainTrue’s study is one of the first to look at levels across western North Carolina in order to gain a general understanding of the amount of microplastics in our water. MountainTrue is partnering with the Waterkeeper Alliance on a state-wide study for all of North Carolina.

Microplastics can enter the environment as plastic litter degrades, in runoff from landfills, and through discharges from wastewater treatment plants. Once in the environment, they can travel for thousands of miles suspended in water or carried by the wind.

MountainTrue is partnering with businesses in Hendersonville to help them shift their operations away from single-use plastics toward reusable bags and compostable utensils and packaging through the Working to be Plastic Free partnership. In Buncombe County and the Town of Boone, MountainTrue is advocating for local ordinances that would encourage the use of reusable shopping bags by replacing single-use plastic bags with paper bags and charging a 10 cent fee that would be waived for shoppers enrolled in the SNAP or WIC programs. To learn how you can support these efforts visit plasticfreewnc.com.

“The first step to stop the contamination of our environment and our bodies is to reduce the amount of plastic that enters and escapes the waste stream,” explains Anna Alsobrook, MountainTrue’s French Broad Watershed Outreach Coordinator. “And that starts by breaking our dependence on single-use plastics like plastic grocery bags and fast food utensils and packaging.”

Microplastics are inadvertently ingested by fish and other aquatic organisms causing microplastics to be transferred throughout the food web. Researchers have found that microplastic ingestion can negatively affect freshwater fish through physical complications of passing plastic through the gut or false satiation. Microplastics can also leach harmful chemicals like plasticizers and additives into the organs of fish. The chemicals have varying effects on fish changing feeding rates, development and survival. Much of the research is focused on centrarchids. Centrarchids are the family of sunfish, and they are a sentinel species, so they are often used to detect risks to humans by providing advance warning of danger.

People consume microplastics in contaminated food and water, and by breathing them in. Microplastics have been found in seafood, salt, tap water and even in bottled water. It is estimated that, globally, people ingest an average of five grams, or the equivalent of a credit card, worth of plastic every week.

The effects of plastic pollution on human health is the subject of a growing body of research. A study has found microplastics small enough to be carried in the bloodstream in the placentas of pregnant mothers. Other research has shown that microplastics cause damage to human cells, including cell death and allergic reactions, at levels known to be consumed in food.

Other research has shown that it’s not just the plastics, but also the additives used to make them can have a harmful effect on human health. Phthalates, which are a family of chemicals used in food packaging, are known endocrine disruptors that harm the reproductive and nervous systems and have been linked to higher rates of childhood asthma and other respiratory conditions. Styrene, which is used to make styrofoam cups, food containers, and disposable coolers, leaches into the food and drinks they hold and from landfills into drinking water. The World Health Organization has classified styrene as a probable human carcinogen.

“These plastics can persist in our environment for hundreds if not thousands of years,” says Anna Alsobrook. “The more we learn about what plastics and the chemicals used to make them are doing to our environment and to our bodies, the clearer it becomes that we need to take action now.”