Paddle trip probes French Broad River’s health

“You cannot know the river by simply sitting on the level banks,” historian and author Wilma Dykeman wrote in her influential 1955 book, The French Broad.

In late June, Mountain Xpress joined the Western North Carolina Alliance for day six of its 11-day paddle down the French Broad. Organized by WNCA staffer and French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson, the trip offered the public a chance to get more intimate with the river while learning about the threats it faces

“We asked the state [Wildlife Resources Commission] to help us with this testing,” Lisenby explained. “But they refused, saying that they do not design a study to investigate a specific source of pollution. So we’re doing this grass-roots style, with citizens participating and learning. If the environmental regulatory agencies don’t do adequate oversight, it becomes incumbent on the people to get involved.”

“We’re like the first responders now,” she continued. “We’re doing what the state should be doing in monitoring the health of the river.”

State records show high levels of mercury in game fish collected from the French Broad in recent years. In at least one case, the mercury level exceeded the Department of Health and Human Services’ limit for fish consumption. (At press time, an analysis of fish-tissue samples collected on this trip was not available because the lab, Pace Analytical in Green Bay, Wis., has been overwhelmed with tissue samples related to the Gulf oil disaster.)

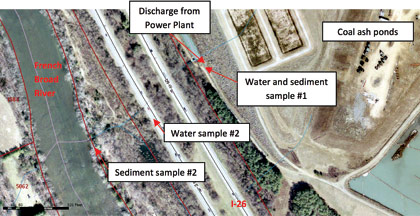

Two coal-ash ponds contained by earthen dams hold the waste products generated by the coal-fired Progress Energy plant — a situation the riverkeepers say is alarmingly similar to the scene of the disastrous 2008 coal-ash spill in Kingston, Tenn. A Tennessee Valley Authority power plant there released 5.4 million cubic yards of coal-ash slurry before flowing into the adjacent Emory River (see “Coal Slurry for a Tennessee Christmas,” Dec. 23, 2008 Xpress). Most coal-ash ponds are situated near rivers, because these power plants typically use surface waters for cooling.

Issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Progress Energy’s wastewater-discharge permit is overseen by the state Division of Water Quality. Scrubbers inside the stacks capture most of the coal ash and other pollutants — including toxic metals such as mercury, lead and arsenic — which eventually end up in the storage ponds. Water, used both for emissions control and for cooling operations, is treated in an artificial wetland where plants and micro-organisms provide a kind of biological cleaning service that helps trap heavy metals and other toxins. The treated wastewater goes over a spillway, through a 36-inch pipe that runs under Interstate 26, and into a small stream that feeds the French Broad.

Progress Energy’s Scott Sutton notes that, since the scrubbers were installed in 2005 and 2006, the plant has achieved “dramatic improvement in its [air] emissions, including an 80 to 90 percent reduction in mercury.” But those toxic materials have to go somewhere, and that somewhere is the open coal-ash ponds above the French Broad.

The EPA recently proposed regulating coal ash as hazardous waste; an alternate proposal would continue the current less stringent requirements, which consider the ash comparable to household trash. Meanwhile, Progress Energy’s discharge permit is up for renewal in December, and even if new rules are approved, they probably won’t be in force by then. Sutton simply says the plant’s storage dam “will meet the standard of the day,” whatever it may be.

Lisenby, however, maintained that the very agencies charged with protecting the public aren’t doing their job. In the wake of the Kingston spill, she says she asked the state’s Aquifer Protection Section if the “coal signature” pollutants from North Carolina’s 13 coal-ash ponds — including one as big as Panther Stadium — were showing up in ground water at the so-called “compliance boundary” surrounding each ash pond. She was shocked to discover that “Aquifer Protection didn’t even know where the compliance boundaries were” for a number of the plants it was supposed to be regulating.

But it doesn’t stop there: Many compliance boundaries, notes Lisenby, are actually in the river or even on the opposite bank. In other words, rather than being protected, the river effectively dilutes the evidence of its own contamination, she contends.

In view of the state-documented problems facing aquatic life in the French Broad, the WNC Alliance wanted to know more about the chemical profile of the wastewater. Accordingly, a small team collected water and sediment samples from two areas: the plant property line just east of I-26, and where the discharge stream meets the river.

Lab analysis of these samples yielded mixed results. Mercury, one of the most persistent toxins emitted by coal-fired plants, was not detected in either of the two water samples. But it was present at appreciable levels in sediment samples.

Similarly, lead wasn’t detected in the water samples but was present in the sediment from both areas, with concentrations as high as 42 ppm at the point nearest the plant. North Carolina has no standard for lead levels in sediment, but the Canadian province of Ontario considers lead levels above 31 ppm in river sediments sufficient to trigger potential legal action.

And though Progress Energy’s current permit doesn’t regulate arsenic (a known toxin), levels in both water and sediment samples sharply exceeded the state limit for maintaining freshwater aquatic life, Carson reports. In the water leaving the plant property, arsenic was found at 181 parts per billion: 18 times our state’s standard for drinking water.

“As things currently stand,” he notes, “Progress can discharge as much arsenic into the river as they like.”

Granted, treated effluent isn’t drinking water. And, as Sutton notes, the state can require the utility to monitor additional pollutants at any time. Plus, “It’s hard to draw conclusions from one or two samples on one day,” he argues. “That’s why we do our sampling weekly, monthly, quarterly. We have specialists on staff at the plants to ensure that we’re in compliance.”

Still, the Alliance’s sampling data does highlight the potential negative consequences for aquatic life in the river.

“The French Broad is primarily a catch-and-release sport fishery,” says Chris Manderson, who provides fishing reports for the French Broad in the online WNC Outdoor Activities Guide (http://ashevillenow.com). “I probably eat fish I catch in the French Broad once or twice a year,” he reports, adding, “It’s not something I worry about.”

In chronicling the French Broad, Dykeman quoted a Cherokee saying: “We have set our names upon your waters and you cannot wash them out.” The same could be said about the heavy metals persisting in the French Broad, river advocates point out.

Susan Andrew can be reached at 251-1333 ext., 153, or atsandrew@mountainx.com .