Michael Franti Returns to Asheville July 27 to Headline the Riverkeeper Beer Series

Michael Franti Returns to Asheville July 27 to Headline the Riverkeeper Beer Series

Michael Franti & Spearhead return to Asheville on Friday, July 27 to headline the Riverkeeper Beer Series at the Salvage Station for the second year in a row. The show is presented by MountainTrue and 98.1 The River, with proceeds supporting the work of the French Broad Riverkeeper – a MountainTrue program that serves as the primary protector and watchdog of the French Broad River Watershed.

“Michael Franti & Spearhead brought such amazing energy to Asheville last year that it was a no-brainer to bring him back for this year’s French Broad Riverkeeper Concert,” says French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson. “Asheville loves Michael and he seems to love us back. Last year he took a surprise tubing float down the French Broad before jumping on stage.”

Michael Franti is a world-renowned musician, filmmaker, and humanitarian who is recognized as a pioneering force in the music industry. Franti believes in using music as a vehicle for positive change and is revered for his energetic live shows, political activism, worldwide philanthropy efforts and authentic connection to his global fan base known as the SOULROCKER FAM.

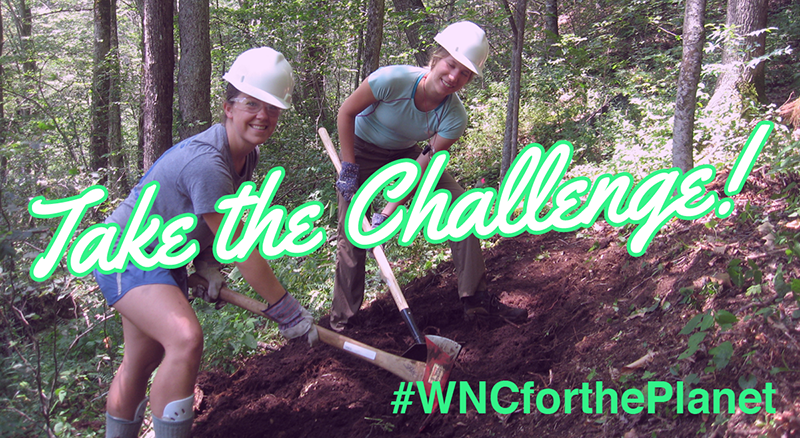

Michael Franti is the headliner for the Riverkeeper Beer Series, presented by Asheville GreenWorks and MountainTrue. Come out for a river cleanup or float during the day and stick around for a special beer release and after-party. There will also be prizes from the Asheville Gear Builders for most trash collected, weirdest trash, and a host of other prizes.Come join the fun this summer at each of these breweries:

June 2 – Cleanup of the Swannanoa River with beer release party at the Wedge at Foundation.

June 28 – Cleanup of the French Broad River with beer release party at Wicked Weed Brewing Pub.

July 21 – Cleanup of the Swannanoa River with beer release party at the Catawba Brewing Company in Biltmore Village.

July 27 – Michael Franti & Spearhead Concert at the Salvage Station.

August 25 – Cleanup of the French Broad River and Hominy Creek with a beer release party at French Broad Outfitters, featuring a tap takeover by Hi-Wire Brewing and live music (artist TBD).

September 8 – Cleanup of the French Broad River with an after-party and concert at Sierra Nevada Brewing Company.

September 15 – Cruise Then Brews Paddle with Headwaters Outfitters. Paddle down the French Broad River in Transylvania County followed by a beer release party at Oskar Blues Brewery.

To learn more information and register for the Riverkeeper Beer Series events, visit MountainTrue.org.

Tickets: Tickets go on sale March 28 at 10am for Michael Franti fan club members, and will go on sale for the general public March 30 at 10am. Tickets are available at the Salvage Station or online at SalvageStation.com. General admission tickets are $33.50 and include a download of Franti’s newest album. VIP tickets are $110 and include a VIP pre party from 5-7pm at the Salvage Station, an acoustic performance by Michael, a fully catered meal, booze at the pre-party and a special roped off viewing area with a private bar.

The Riverkeeper Series is sponsored by MountainTrue, Asheville GreenWorks, 98.1The River and French Broad Outfitters. Other sponsors include Wedge Brewing Company, Wicked Weed Brewing Pub, New Belgium Brewing Company, Sierra Nevada Brewing Company, Oskar Blues Brewery, Sanctuary Brewing Company, Catawba Brewing Company, WNC Magazine, Mountain Xpress, and Recover Brands.

MountainTrue champions resilient forests, clean waters and healthy communities in our region. We engage in policy advocacy at all levels of government, local project advocacy and on-the-ground environmental restoration projects. Primary program areas include public lands, water quality, clean energy, land use/transportation and citizen engagement. We are also home to Riverkeepers for the French Broad, Watauga, Green and Broad Rivers, who are the primary defenders and spokespeople for these waterways. For more information: mountaintrue.org.

With thousands of volunteers, Asheville GreenWorks engages the community in grassroots projects such as urban forestry, environmental cleanups, anti-litter and waste reduction education, creation of green spaces, care and preservation of Asheville’s rivers and trees. Through our work, Asheville has been designated as a Tree City USA for 37 years.

###