Let’s chat bugs! Last December on the MountainTrue blog, we considered What’s Bugging Our Rivers. Today, we’ll take a deeper dive into our participation in the Stream Monitoring Information Exchange (SMIE) program and our partnership with the Environmental Quality Institute (EQI), based in Black Mountain, NC. We’ll split this blog post into two main sections: we’ll start with a summary of the SMIE program and our partnership with EQI and conclude with a brief SMIE volunteer FAQ.

About SMIE

SMIE is a collaborative, volunteer-based biological water quality monitoring program that analyzes aquatic macroinvertebrate population data from across Western North Carolina (WNC). The SMIE program was developed in 2004 by Clean Water for North Carolina (CWFNC) (as creative lead), EQI, Haywood Waterways Association, Riverlink, and two of MountainTrue’s predecessor organizations: the Environmental Conservation Organization (ECO) and the WNC Alliance.

Benthic macroinvertebrates — including aquatic stream bottom-dwelling insects like stoneflies, caddisflies, hellgrammites, and more — are excellent indicators of the comprehensive water quality of a stream because they have limited mobility, specific habitat requirements, and distinct pollution tolerance levels. You could say that aquatic macroinvertebrates are artists — they paint a revealing picture of the overall health of aquatic ecosystems. As the metaphorical art historians of the SMIE world, experts at EQI and their partner organizations analyze the physical cues left by these tiny yet essential aquatic insect artists. The expert analyses of SMIE data across multiple watersheds help us better understand our region’s vibrant water quality history and present reality.

About EQI and MountainTrue’s partnership

Our partnership began in 1992 when EQI partnered with ECO — one of MountainTrue’s three predecessor organizations — to conduct surface water monitoring in Henderson County as part of EQI’s *Volunteer Water Information Network (VWIN) program. Thirty years (and a whole lot of water quality testing) later, MountainTrue continues to collect and deliver monthly water quality samples to EQI, and we now provide EQI with our SMIE data for analysis.

One of EQI’s primary goals is to increase public awareness about regional water quality and environmental issues across WNC. Involving the public in the SMIE data collection process allows EQI and MountainTrue to significantly expand our sampling capacity and add credibility to citizen science programs.

EQI currently coordinates SMIE sampling at 49 sites in five WNC counties (Buncombe, Madison, Haywood, Mitchell, and Yancy). EQI also provides technical support for its partner organizations using the SMIE protocol throughout WNC and Eastern TN. As an EQI partner, MountainTrue coordinates SMIE volunteer training and sampling in Henderson, Polk, and Cleveland counties. SMIE sampling efforts occur each spring and fall, typically in April and October.

Check out EQI’s Water Quality Map to see sampling locations and review data from the past 30 years of water quality monitoring!

*One of EQI’s major programs, VWIN is a volunteer-based network that has been conducting chemical surface water monitoring in WNC streams on a monthly basis since 1990. Learn more about and get involved with EQI’s VWIN work here.

Why our partnership matters

The North Carolina Division of Water Resources (NC DWR) monitors water quality throughout the state, prioritizing testing sites with existing and pressing issues. The agency’s minimal number of testing sites and low sampling frequency have both continued to decrease over time due to lack of capacity — this means that water quality in many WNC streams is not regularly monitored… That’s where we come in!

The SMIE program monitors the water quality of urban, rural, and forested streams in priority WNC watersheds and tributaries without existing watershed plans or projects. By consistently monitoring WNC streams, EQI and MountainTrue can assess long-term water quality trends that highlight the interrelated relationship between the health of local waterways and resident aquatic insect populations.

This comprehensive knowledge provides valuable insights into the effects of *pollution in our local waterways. Essentially, WNC streams with higher pollution levels have fewer aquatic insects and are less hospitable to other aquatic and riparian species, like native fish, salamanders, and streamside plants. Alternatively, the presence of pollution-sensitive aquatic insect species indicates cleaner, healthier streams with greater biodiversity.

*The most common types of pollution include:

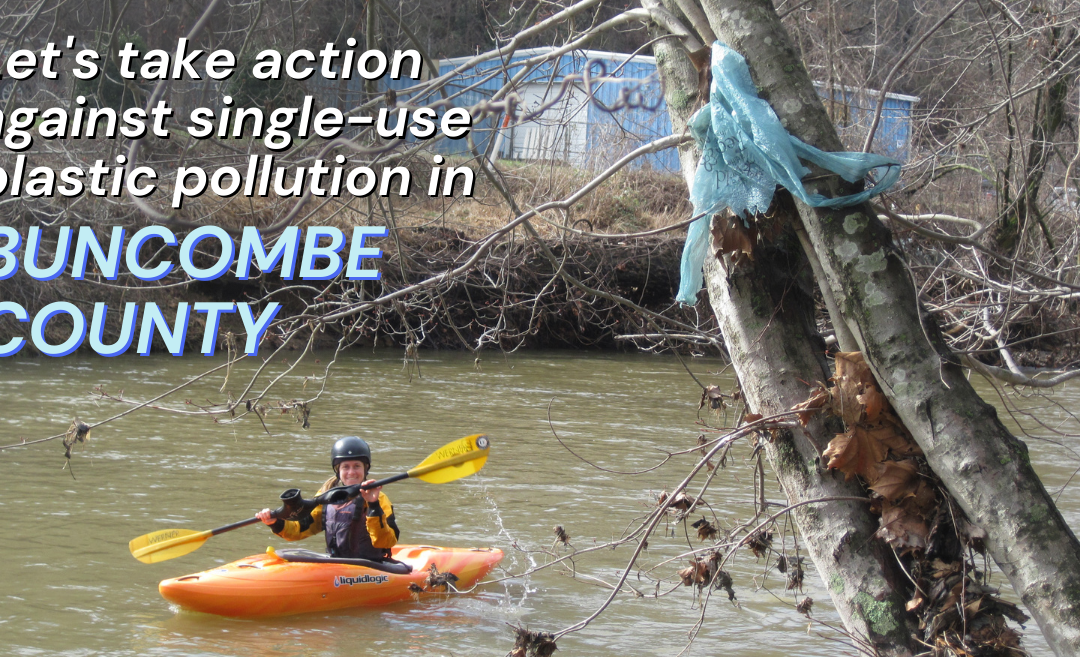

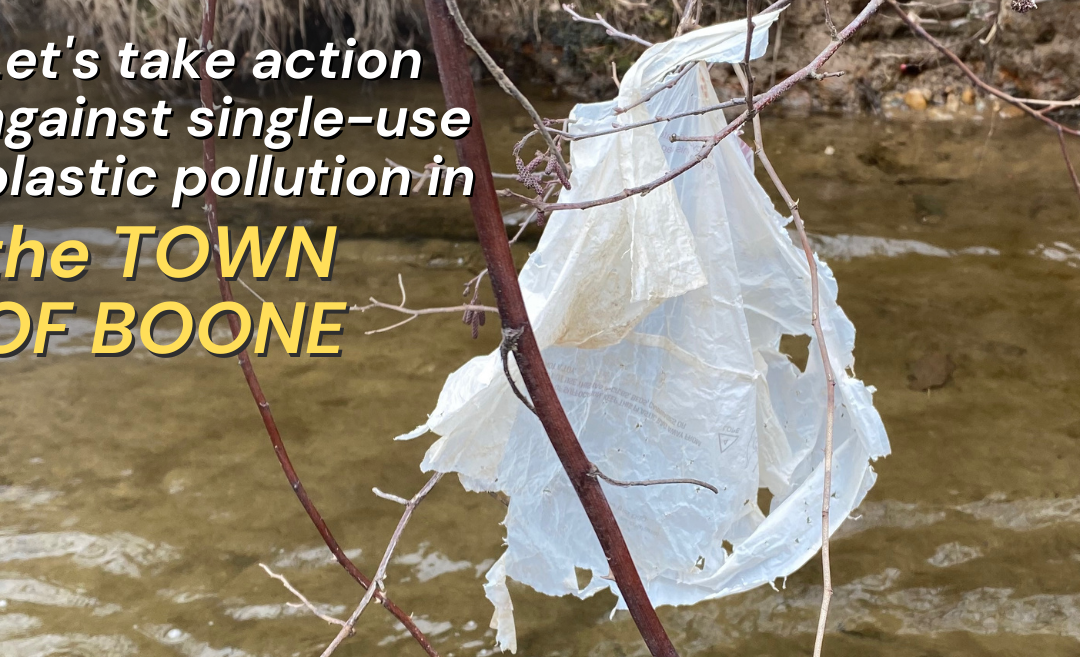

- Stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces like parking lots, roads, buildings, and other structures. Littered trash is frequently swept up in the flow of running stormwater, quickly making its way into local waterways.

- Bacteria and chemical pollution, often caused by sewer and septic system overflows, agriculture runoff, and industrial effluent.

- Sediment pollution, often caused by erosion of stream banks, some animal agriculture practices, and runoff from construction sites and plowed fields.

- Wastewater human and animal waste, industrial effluent, and trash.

SMIE Volunteer FAQ

Q: Why should folks want to volunteer for SMIE?

It’s a super fun way to connect with the environment and your community through citizen science and shared experience. SMIE volunteers get hands-on experience with a unique and essential facet of environmentalism (aquatic insects!) and make meaningful contributions to environmental protection!

Q: What does a typical SMIE volunteer day look like?

MountainTrue or EQI’s SMIE experts meet volunteers at our sampling sites and provide all the supplies needed for a day of aquatic insect sampling: nets, buckets, filters, ice cube trays, forceps, datasheets, and waterproof waders. A group leader accompanies each volunteer group, completing all aquatic insect identification and ensuring proper SMIE protocol is followed. The data collected by SMIE volunteers is recorded and sent back to the EQI or MountainTrue labs, where it’s entered into our long-term database.

In total, sampling an SMIE site takes between one and a half to three hours. Volunteers are expected to sample at least two SMIE sites each spring and fall season. We collect our samples using the three collection methods detailed in the SMIE protocol: