MountainTrue’s June 2023 E-Newsletter

MountainTrue’s

June 2023 E-Newsletter

June news from MountainTrue’s four regional offices:

Central Region News

Click here to read

High Country News

Click here to read

Southern Region News

Click here to read

Western Region News

Click here to read

Central Region News

A note from Gray Jernigan, Deputy Director & General Counsel:

It’s hard to believe we’re almost halfway through the year, and now that summer is in high gear, our team is spending a lot of time outside on the water, in the woods, and in our communities. We’re taking weekly water samples to inform the public about where it’s safe to recreate in our mountain waters, guiding hikes to educate participants about public lands, and spreading the word at local events about our work and how to get involved.

While it might not sound as fun as getting outside, another important side of our work has been happening at the General Assembly in Raleigh. Our staff has taken four trips to the state capitol this legislative session to meet with lawmakers about our priorities for Western North Carolina, and our contract lobbyist has been “carrying our water” every day in between. We advocate on bills passing through the chambers and try to improve legislation as it moves. Our biggest legislative advocacy focus is on the state budget that allocates funding for programs and projects that, among other things, can improve public access to rivers and forests, protect water quality, and expand conservation of natural resources. To stay up to date on all the happenings at the General Assembly and our advocacy work there, sign up to receive the MountainTrue Raleigh Report.

Of course, this work can’t happen without the generous support of our members, people just like you, who join our commitment to protect the places we share. Any amount helps, and you can even start with a small monthly donation that fits your budget. Join us by making a donation today. Now get out there and enjoy the summer, and while you do, remember to join in the MountainTrue-a-thon as you hike, bike, and paddle! We’ll see you out there!

MountainTrue’s State of Our Rivers Report details health of our waters, likely sources of pollution, and policy solutions

Learn about the health of our waterways with MountainTrue’s new State of Our Rivers Report, which leverages a year’s worth of data to give the public a better understanding of the water quality of the rivers, streams, and lakes of the Southern Blue Ridge Mountains. For the first time, this report outlines likely sources of pollution and provides legislators, stakeholders, and advocates with a set of targeted policy solutions to protect the health of our waters, our communities, and our multi-million dollar water recreation economy. Read the report at stateofourrivers.report.

See French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson discuss the findings of the report with WLOS News.

Have you signed up for the MountainTrue-a-thon yet?

There’s still time to sign up for the 2023 MountainTrue-a-thon, which kicks off on June 15 and runs through August 31. Earn money for MountainTrue while doing your favorite activities: hiking, biking, and paddling — it’s a win-win! Lace up your boots, grab your gear, and let’s hit the trails for some adventure.

P.S. Did we mention there are PRIZES for the top $ earner and most pledged miles hiked?!

Bioblitz with us in the Craggies

MountainTrue’s 2023 Bioblitz is happening now until June 25 in the Craggy Mountains! The Bioblitz is an annual event – hosted by MountainTrue on iNaturalist – that seeks to get experts, naturalists, and curious others outdoors to document every living organism we can find. The information you collect will be crucial in documenting the special character of the area, helping the Forest Service to better protect it, and in demonstrating to Congress that it should be designated a permanently protected National Scenic Area. Click here to learn more about the Bioblitz and sign up to participate.

Jam with Michael Franti, MountainTrue, and your French Broad Riverkeeper

Join us for the 2023 Michael Franti & Spearhead concert featuring Fortunate Youth at the Salvage Station on July 8 in Asheville, NC! All proceeds from the concert support the work of the French Broad Riverkeeper, a program of MountainTrue and the primary protector and defender of the French Broad River watershed. Get your tickets now! Doors open at 6 p.m. and music starts at 7 p.m. There will be several food trucks and full bars open for you to enjoy! Please visit the Salvage Station’s event page for the most up-to-date information, tickets, parking information, and other FAQs.

Photo: French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson and family paddle the river on a previous paddle trip.

The countdown to the 2023 French Broad Paddle Trip is on!

Every year, MountainTrue and the French Broad Riverkeeper guide participants on an incredible trip down a stretch of the French Broad River, creating lasting memories exploring what can feel like uncharted territory right in our own backyards and camping under the stars on the French Broad River Paddle Trail. Leave the hustle behind and experience the joys of river travel while having your meals provided, your campfire built, and your gear transported for you to your next campsite! This year’s trip will take place July 12-14, with an option to add a one-day paddle down Section 9 of the French Broad on July 11 to your ticket purchase. Click here to learn more and reserve your spot!

Welcome to our new Development & Operations Coordinator

The Development team is thrilled to welcome Sydney Swafford as our new Development & Operations Coordinator. Sydney most recently filled our Outings, Education, and Forest Stewardship Coordinator position with AmeriCorps. She brings hands-on experience with her Environmental Science degree and years of organizational management in her personal and professional life. She can be reached at sydney@mountaintrue.org.

Local grocer makes a stand against plastic pollution

Founded as Amazing Savings in the early 2000s, Hopey and Company is a locally-owned grocery store specializing in artisan and discount food and beverages. With locations in Asheville and Black Mountain, Hopey & Co is leading the charge to ban plastic bags from retail establishments. Starting July 1, 2023, Hopey & Co will no longer offer plastic bags when you pay for your groceries. Hopey & Co currently offers these in-store alternatives to single-use plastic bags:

- Cardboard boxes conveniently located in a bin by the checkout

- Two sizes of reusable grocery bags

We’re thankful for businesses like Hopey & Co, who are helping to pave the way for a more sustainable future. Show your support for a single-use plastic bag ban by taking your reusable bags when you shop! Visit plasticfreewnc.com to learn more about our collaborative efforts to bring about a Plastic-Free WNC.

Save the date: MountainTrue launches new housing program!

MountainTrue is excited to be launching Neighbors for More Neighbors WNC on August 10 with a kickoff event in Asheville. Where we live shapes our lives and our long-term success — from the length and cost of our commute to where we shop for groceries, and where we send our children to school. Neighbors for More Neighbors WNC will advocate for policies and projects that will create more housing choices close to town centers; creating the kinds of walkable, convenient communities that are good for both people and the planet. Save the date and join us to learn how you can be involved!

Buncombe County residents: take the Buncombe Open Space Bond Survey

Buncombe County is seeking your help in setting the community vision for the future of Buncombe County recreation. The county recently opened a six-question survey to gather public feedback about passive recreation lands. The passage of the Open Space Bond in November 2022 cleared the way for the development of Passive Recreation Lands in Buncombe County. These lands provide opportunities for outdoor activities that require minimal stress on a site’s resources. As the Open Space Bond funds allow more lands to be purchased or protected in conservation easements, more areas of Buncombe County can be enjoyed for passive recreation activities.

Film premiere: Nature’s Wisdom Thru Native Eyes

Long-time Henderson County environmental advocate, filmmaker, and cultural preservationist, David Weintraub, invites the community to the premier events for his newest film, Nature’s Wisdom Thru Native Eyes. The film integrates native storytelling and philosophy with cutting-edge science that affirms what native peoples have been saying about the intelligence of nature for thousands of years! Local premiere dates include Saturday, June 24 at North River Farms in Mills River, NC (drive-in theater) and Saturday, July 1 at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Hendersonville, NC. The starting time at all venues is 7:30 p.m. Find out more here.

High Country News

A note from Andy Hill, High Country Regional Director & Watauga Riverkeeper:

It’s a special time of year for river people with warm weather and spring flows. We have been taking advantage of the clear water to enjoy river snorkeling, paddle trips, and cleanups. Our Swim Guide water quality sampling program is in full swing, with results published weekly on the Swim Guide app.

This week also marks the retirement of our beloved Ecologist and Public Lands Director, MountainTrue legend Bob Gale (or Sweet Bobby G as we call him). Bob has been with MountainTrue for over 25 years and has been a tremendous asset to conservation efforts in the Southern Blue Ridge. Please join me in expressing your gratitude for his years of service. You can send your kind words to bob@mountaintrue.org.

Consider supporting our very talented staff by becoming a MountainTrue member and contributing to our mission of protecting the places we share! Join us by making a donation today.

Weekend plans: Riverkeeper Float Fest!

Ready to ring in the summer? Riverkeeper Float Fest is back and better than ever! Join MountainTrue’s Watauga Riverkeeper and High Country Water Team on Saturday, June 24, for a fun-filled, family-friendly event from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. at River & Earth Adventures’ New River Outpost in Todd, NC. Rain or shine, shuttles will be going all day from Peacock traffic circle in Boone to ensure safe transportation to and from the festival. Our friends at Appalachian Mountain Brewery will be providing the jams, good brews, and fantastic food all day long. Spend your day chilling out, listening to music and snacking with friends, or tube down the New River and enjoy fly fishing demos from our buddies at Boone’s Fly Shop. Ticket levels are available for tubing, general admission, designated drivers, and kids 12 and under are FREE — click here to get your tickets.

MountainTrue’s State of Our Rivers Report details health of our waters, likely sources of pollution, and policy solutions

Learn about the health of Western North Carolina’s waterways with MountainTrue’s new State of Our Rivers Report, which leverages a year’s worth of data to give the public a better understanding of the water quality of the rivers, streams, and lakes of the Southern Blue Ridge Mountains. For the first time, this report outlines likely sources of pollution and provides legislators, stakeholders, and advocates with a set of targeted policy solutions to protect the health of our waters, our communities, and our multi-million dollar water recreation economy. Read the report at stateofourrivers.report.

Photos: Hannah Woodburn and recent App State grad and research technician, Quentin LaChance, pose with a hellbender (left). Hannah Woodburn safely handles a hellbender that the group captured and tagged for long-term monitoring (right). Photo credit: Henry Gates.

Hellbender surveys on the Upper Watauga River

Along with the first week of Swim Guide, our Watauga Riverkeeper team was busy searching for hellbenders during the last week of May. We teamed up with the NC Wildlife Resources Commission and Appalachian State University’s Aquatic Conservation Research Lab to assess river habitat and monitor local populations of sensitive aquatic salamanders. Our Watershed Coordinator and biologist, Hannah Woodburn, was the first of the snorkeling group to spot a baby hellbender! Over the course of the two-day search, 24 hellbenders were captured and tagged for long-term monitoring. We thank all of the dedicated professionals, students, and volunteers who contributed to the success of the surveys!

Swim Guide launch at Valle Crucis Community Park

To kick off the 2023 Swim Guide season, our Water Team hosted a launch party on May 11 at Valle Crucis Community Park for our trusty volunteers. We discussed safety, protocols, and how awesome this summer will be! We had a great time connecting with our volunteers and we sincerely appreciate their help. Our annual Swim Guide program monitors E. coli levels at popular High Country swimming sites and runs until September 6, 2023. Our small mountain community is one of many contributing to an international effort to monitor bacteria levels at local “beaches” or, in our case, lakes or streams.

Want to volunteer with our Swim Guide program? Sampling sites are assigned on a first-come, first-served basis, but we encourage folks to sign up to join our list of backup Swim Guide volunteers! (Sampling typically requires a 1 to 2-hour commitment, once per week).

Photos: The full Winkler’s Creek Trash Trout in Boone, NC, before a routine cleanup.

An update on the Tennessee Trash Trouts

Another month, another Trash Trout cleanout! Last month, we hopped across the Tennessee line and paid a visit to the two Trash Trouts monitoring macroplastics in waterways for our neighbors in East TN. Cleaning out these passive litter collection devices is a great way to get outside, help keep the river clean, and have fun! The TN Trash Trouts are located on Buffalo Creek and Doe River, and they serve as indicators of the trash levels that flow through the channel over a certain amount of time. We appreciate our community partners who helped implement this plastics monitoring tool!

Bioblitz with us in the Craggies and at Valle Crucis Community Park

MountainTrue’s 2023 Bioblitz is happening now until June 25 in the Craggy Mountains! The Bioblitz is an annual event – hosted by MountainTrue on iNaturalist – that seeks to get experts, naturalists, and curious others outdoors to document every living organism we can find. The information you collect will be crucial in documenting the special character of the area, helping the Forest Service to better protect it, and in demonstrating to Congress that it should be designated a permanently protected National Scenic Area. Click here to learn more about the Bioblitz and sign up to participate.

Join our High Country team for the 3rd annual Bioblitz at Valle Crucis Community Park on Sunday, July 23! Stop by anytime between 9:30 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. to explore the meadows and wetlands along the river and help us find and identify as many different plants, animals, and fungi as we can for the park’s species list! Register here.

Chatting about sustainability in the workplace at Watauga High School

Our High Country Watershed Coordinator, Hannah, led a talk for AP Environmental Science students at Watauga High School on May 9 centered around careers and professional development within the scientific community. The students chatted about conservation, ecology, career development, and highlighting the work of other nonprofit organizations in the High Country dedicated to protecting the places we share! Our Water Team loves educational outreach — most of the time, we learn from the students as much as they learn from us. Thank you to Courtney Capozzoli and Watauga High School for allowing us to chat with these future scientists!

Have you signed up for the MountainTrue-a-thon yet?

There’s still time to sign up for the 2023 MountainTrue-a-thon, which kicks off on June 15 and runs through August 31. Earn money for MountainTrue while doing your favorite activities: hiking, biking, and paddling — it’s a win-win! Lace up your boots, grab your gear, and let’s hit the trails for some adventure.

P.S. Did we mention there are PRIZES for the top $ earner and most pledged miles hiked?!

Welcome to our new Development & Operations Coordinator

The Development team is thrilled to welcome Sydney Swafford as our new Development & Operations Coordinator. Sydney most recently filled our Outings, Education, and Forest Stewardship Coordinator position with AmeriCorps. She brings hands-on experience with her Environmental Science degree and years of organizational management in her personal and professional life. She can be reached at sydney@mountaintrue.org.

Southern Region News

A note from Nancy Díaz, Southern Regional Director:

I recently had the pleasure of joining our long-time Ecologist and Public Lands Director, Bob Gale, on the Lewis Creek Nature Preserve Walk, a conservation property just a few minutes away from my old high school. I continue to be amazed by all the rich natural resources in our little piece of WNC and by the people who carry and share their expertise selflessly and with so much passion. In this message, I want to express gratitude to Bob for all his contributions to environmental advocacy and education in MountainTrue’s Southern Region — happy retirement, Bob!

Consider supporting our very talented staff by becoming a MountainTrue member and contributing to our mission of protecting the places we share! Join us by making a donation today.

MountainTrue’s State of Our Rivers Report details health of our waters, likely sources of pollution, and policy solutions

Learn about the health of Western North Carolina’s waterways with MountainTrue’s new State of Our Rivers Report, which leverages a year’s worth of data to give the public a better understanding of the water quality of the rivers, streams, and lakes of the Southern Blue Ridge Mountains. For the first time, this report outlines likely sources of pollution and provides legislators, stakeholders, and advocates with a set of targeted policy solutions to protect the health of our waters, our communities, and our multi-million dollar water recreation economy. Read the report at stateofourrivers.report.

See French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson discuss the findings of the report with WLOS News.

Clean the Green River with us this summer

Join Green Riverkeeper Erica Shanks on the river this summer for our 2023 Green Clean Series! This recurring event will happen from 5:30-8 p.m. on the 4th Thursday of each month from June-August, 2023. You don’t have to kayak to be a part of the monthly cleanups — roadside volunteers are also welcome! Click here to learn more and sign up! Join your Green Riverkeeper at the Green River Brew Depot in downtown Saluda after each cleanup! The Brew Depot will be giving one free beer to each volunteer who attends the cleanup and presents a ticket. Additionally, The SPOT will offer volunteers a free drink to enjoy within a week of their participation in the cleanup!

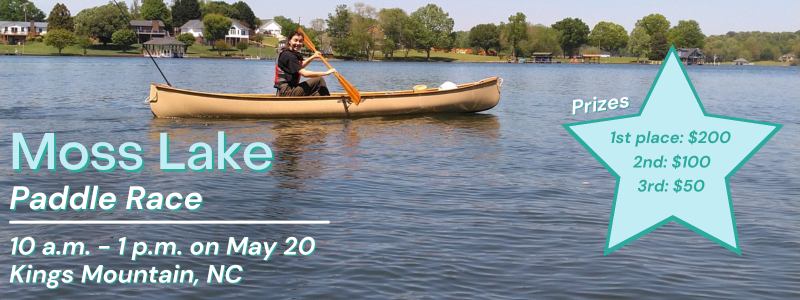

Join us for the 5th annual Broad River Race Day

The 5th annual Broad River Race is happening from 1-4:00 p.m. on Saturday, July 8, in Mooresboro, NC! The Broad Riverkeeper welcomes folks to race at their own pace and enjoy paddling five miles on the most beautiful stretch of the Broad River. Participants will meet at the Lake Houser put in at 1 p.m. to drop off their boats, and the race will begin at 2 p.m. The first person or first team across the finish line wins a MountainTrue gift bag and takes possession of Betsy the Turtle until next year’s race (a cool wooden turtle carved by Broad Riverkeeper David Caldwell)! This race only has two rules: You MUST wear a pfd and no motors allowed. You can paddle solo, tandem, or with as many people as you can fit in your boat. Click here to learn more and register.

Photo: Folks enjoy the cool waters along the Broad River Greenway in Cleveland County.

Broad Riverkeeper Swim Guide sponsor highlight: Shelby Women for Progress

Shelby Women for Progress (SW4P) is a women-led, Shelby-based, advocacy group “supporting progressive women throughout the county, and beyond, by building an inclusive network of member-led advocacy.” SW4P believes that “organizing a community means creating and maintaining a system where people can work together to meet common goals that benefit the community.” This strong group of women can indeed organize, engage, and get things done! SW4P recently held a fundraiser for your Broad Riverkeeper and MountainTrue, which financed their sponsorship of our Swim Guide site at the Broad River Greenway — the Broad River’s most popular swimming location. Group leader Stevie Brooks said, “Shelby Women for Progress is a homegrown organization dedicated to making Cleveland County an inclusive and safe place for all. SW4P is honored to be helping ensure that accessible recreational areas, like our rivers, are maintained and monitored to be enjoyed safely by the residents of Cleveland County.” Thanks, SW4P!

Want to sponsor your favorite swimming spot along the Broad or Green rivers? Businesses and individuals can sponsor Swim Guide sampling sites! Contact MountainTrue Development Director Adam Bowers (adam@mountaintrue.org) or click here to learn more about pricing and benefits.

Bioblitz with us in the Craggies

MountainTrue’s 2023 Bioblitz is happening now until June 25 in the Craggy Mountains! The Bioblitz is an annual event – hosted by MountainTrue on iNaturalist – that seeks to get experts, naturalists, and curious others outdoors to document every living organism we can find. The information you collect will be crucial in documenting the special character of the area, helping the Forest Service to better protect it, and in demonstrating to Congress that it should be designated a permanently protected National Scenic Area. Click here to learn more about the Bioblitz and sign up to participate.

Photo: Green Riverkeeper Erica Shanks and superstar SMIE volunteer, Lee McCall, collect aquatic macroinvertebrates during an SMIE field day in Fletcher, NC.

Looking for bugs + documenting stream health with the Green Riverkeeper

SMIE (Stream Monitoring Information Exchange) season kicked off to a great start! We’ve been able to visit 17 sites so far this spring season, and we’ve found over 500 aquatic macroinvertebrates throughout our different streams and rivers. We’ve identified different species of caddisflies, mayflies, dragon and damselflies, salamanders and more! We’re always looking for volunteers to join our SMIE team, so reach out if you’re interested in playing in the water with your Green Riverkeeper!

Have you signed up for the MountainTrue-a-thon yet?

There’s still time to sign up for the 2023 MountainTrue-a-thon, which kicks off on June 15 and runs through August 31. Earn money for MountainTrue while doing your favorite activities: hiking, biking, and paddling — it’s a win-win! Lace up your boots, grab your gear, and let’s hit the trails for some adventure.

P.S. Did we mention there are PRIZES for the top $ earner and most pledged miles hiked?!

Photo: The 2023 Spring Clean on the Green crew poses for a photo.

Green Riverkeeper Erica Shanks on a successful Spring Clean on the Green & Green River Bash:

We hosted our 13th annual Spring Clean on the Green with LiquidLogic Kayaks co-founder Shane Benedict last month, and it was one for the books! Volunteers helped us pull 21 bags of trash, three tires, three tubes, a radiator, and plastic bits from the Narrows, Lower Green, and roadside sections of the Green River Gorge. Big shoutout to everyone who came and lent a hand. The weather was perfect and we left the Green cleaner than we found it!

The cleanup’s afterparty also happened to be the Spring Green Bash at Green River Adventures. The Spring Green Bash is always my favorite day of the year here in Saluda! It was awesome to connect with my community in my role as your Green Riverkeeper and sell some raffle tickets to support MountainTrue’s work! I’m stoked that the mom and daughter team who won the raffle will be taking their new LiquidLogic kayak down the Grand Canyon this August! Thanks for showing some big love that weekend, y’all. I’m always grateful for this community, and look forward to doing it all again next year!

Welcome to our new Development & Operations Coordinator

The Development team is thrilled to welcome Sydney Swafford as our new Development & Operations Coordinator. Sydney most recently filled our Outings, Education, and Forest Stewardship Coordinator position with AmeriCorps. She brings hands-on experience with her Environmental Science degree and years of organizational management in her personal and professional life. She can be reached at sydney@mountaintrue.org.

Film premiere: Nature’s Wisdom Thru Native Eyes

Long-time Henderson County environmental advocate, filmmaker, and cultural preservationist, David Weintraub, invites the community to the premier events for his newest film, Nature’s Wisdom Thru Native Eyes. The film integrates native storytelling and philosophy with cutting-edge science that affirms what native peoples have been saying about the intelligence of nature for thousands of years! Local premiere dates include Saturday, June 24 at North River Farms in Mills River, NC (drive-in theater) and Saturday, July 1 at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Hendersonville, NC. The starting time at all venues is 7:30 p.m. Find out more here.

Western Region News

A note from Callie Moore, Western Regional Director:

While searching for inspiration about the month of June, I ran across a list of the top ten best places in the U.S. to visit in June. Of course, the list mentioned the national parks out west that are shifting from snow into spring and the coastal beaches that aren’t too hot yet. Since I’m not likely to be going to any of those far-flung places this year, I started thinking about places closer to home. One of the best places I can think of visiting in the Southern Blue Ridge in June is the Craggy Mountains, which are typically resplendent with wild rhododendron blooms in mid-June. As luck would have it, MountainTrue’s 2023 BioBlitz is happening right now in that very same mountain range!

Another really neat June-blooming plant is the mountain camellia, also known as mountain Stewartia or summer dogwood. These can be found growing along the Cover Trail in Fires Creek Wildlife Management Area, among other places in both Nantahala and Chattahoochee National Forests. Synchronous fireflies are another amazing wonder of nature in these mountains in June, and lots of our darter (fish) species are donning their brilliant spawning colors this month. If you’ve never been freshwater snorkeling, I encourage you to check it out! Thank you in advance for reading on, and know that all this work couldn’t happen without your support. Thank you for being MountainTrue!

MountainTrue’s State of Our Rivers Report details health of our waters, likely sources of pollution, and policy solutions

Learn about the health of Western North Carolina’s waterways with MountainTrue’s new State of Our Rivers Report, which leverages a year’s worth of data to give the public a better understanding of the water quality of the rivers, streams, and lakes of the Southern Blue Ridge Mountains. For the first time, this report outlines likely sources of pollution and provides legislators, stakeholders, and advocates with a set of targeted policy solutions to protect the health of our waters, our communities, and our multi-million dollar water recreation economy. Read the report at stateofourrivers.report.

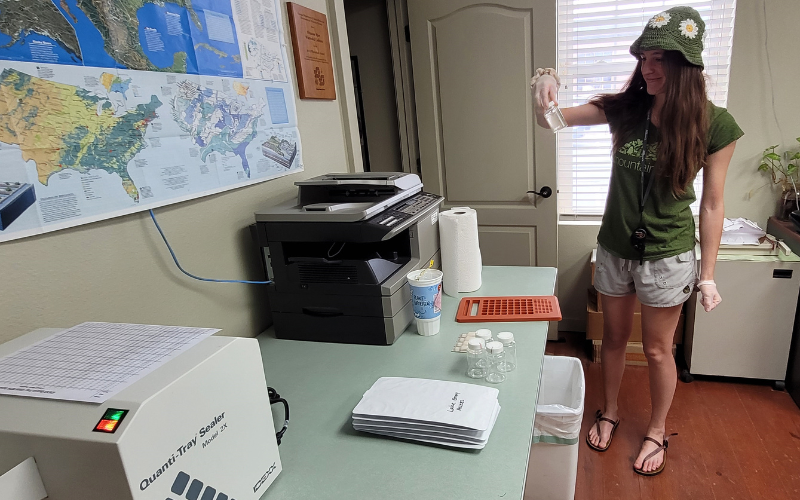

Photo: AmeriCorps member Darby Stipe processes Swim Guide samples from the Little Tennessee River basin.

Swim Guide launched in the Little Tennessee River basin!

MountainTrue has added another river basin to its summer Swim Guide program of weekly E. coli monitoring with six new locations on the Little Tennessee and Nantahala Rivers. We also added another site in the Hiwassee River basin for a total of 14 locations this year! MountainTrue’s Swim Guide program is powered by volunteers and staff who collect water samples mid-week and rush to process, analyze, and post the results on the swimguide.org website and smartphone app in time for your weekend fun. While the primary purpose of Swim Guide is to inform you about where it’s safe to swim, we use the data to help solve water quality problems, as well as to inform our advocacy and push for science-based policy solutions.

Want to sponsor your favorite swimming spot in MountainTrue’s Western Region? Businesses and individuals can sponsor Swim Guide sampling sites! Contact MountainTrue Development Director Adam Bowers (adam@mountaintrue.org) or click here to learn more about pricing and benefits.

Housing discussion forum in Clay County tomorrow evening

MountainTrue is hosting a discussion forum at 5:30 p.m. tomorrow evening, June 20, at Hinton Rural Life Center near Hayesville, NC. In response to the severe housing shortage in our region and the climate crisis, MountainTrue is launching a new pro-housing program called Neighbors for More Neighbors WNC (which will also be active in North Georgia), in support of building small-scale and multi-family housing in more walkable places. The purpose of the forum is to learn what our members think this work should look like in rural areas. If you’re interested in this topic, please contact MountainTrue’s Housing & Transportation Director, Susan Bean to learn more or RSVP: susan@mountaintrue.org.

Photo: More than 30 volunteers worked to remove nonnative invasive plants and restore native habitat along the Jackson County Greenway this past winter and spring.

Thank you, Jackson County Greenway volunteers!

We had a great first season of removing invasive plants along the Tuckasegee River and the Jackson County Greenway in partnership with Mainspring Conservation Trust. Volunteers showed a great deal of dedication and hard work helping us improve the biodiversity of our shared lands. During our first season working the Greenway, we hosted three workdays with a total of 33 individuals contributing nearly 100 hours. In addition to getting a lot of work done, all of that volunteer time resulted in $2,965.05 in matching funds that can be applied to grants!

Have you signed up for the MountainTrue-a-thon yet?

There’s still time to sign up for the 2023 MountainTrue-a-thon, which kicks off on June 15 and runs through August 31. Earn money for MountainTrue while doing your favorite activities: hiking, biking, and paddling — it’s a win-win! Lace up your boots, grab your gear, and let’s hit the trails for some adventure.

P.S. Did we mention there are PRIZES for the top $ earner and most pledged miles hiked?!

Bioblitz with us in the Craggies

MountainTrue’s 2023 Bioblitz is happening now until June 25 in the Craggy Mountains! The Bioblitz is an annual event – hosted by MountainTrue on iNaturalist – that seeks to get experts, naturalists, and curious others outdoors to document every living organism we can find. The information you collect will be crucial in documenting the special character of the area, helping the Forest Service to better protect it, and in demonstrating to Congress that it should be designated a permanently protected National Scenic Area. Click here to learn more about the Bioblitz and sign up to participate.

Welcome to our new Development & Operations Coordinator

The Development team is thrilled to welcome Sydney Swafford as our new Development & Operations Coordinator. Sydney most recently filled our Outings, Education, and Forest Stewardship Coordinator position with AmeriCorps. She brings hands-on experience with her Environmental Science degree and years of organizational management in her personal and professional life. She can be reached at sydney@mountaintrue.org.