The U.S. Forest Service has announced a plan to amend all 128 forest management plans nationwide —...

MountainTrue and Conservation Groups prepare for lawsuit over Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan

MountainTrue and Conservation Groups prepare for lawsuit over Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan

Photo of a Virginia big-eared bat by Larisa Bishop-Boros – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32046949

MountainTrue has joined a coalition of conservation groups in sending a letter to the U.S. Forest Service, signaling our intent to sue over glaring flaws in the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan.

MountainTrue Statement:

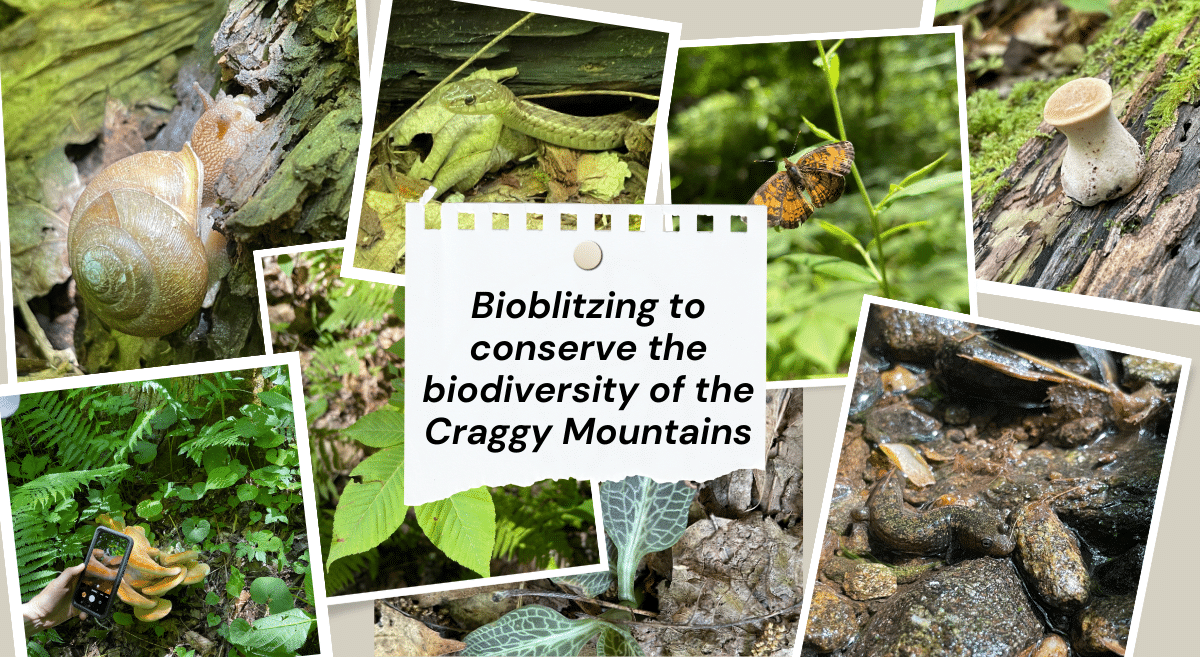

The US Forest Service’s management plan for the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests is deeply flawed. The Forest Service put commercial logging first, ignored the best science available, and is needlessly putting several endangered bat species at risk of extinction. The endangered species that would be affected are the northern long-eared bat, Indiana bat, Virginia big-eared bat, and the gray bat. Two species that are being considered for the endangered species list — the little brown bat and the tricolored bat — would also be adversely affected.

From the beginning of the drafting process, we’ve tried to work in partnership with the Forest Service and many other stakeholders to develop a responsible win-win plan for the environment, our economy, and the people of our region. MountainTrue and our experts remain ready and willing to help the Forest Service fix its plan and make it more ecologically responsible and more responsive to the needs of our communities.

Our incredibly diverse ecosystems deserve a better plan. The people who love and use these forests deserve a better plan. And MountainTrue and our litigation partners are willing to go to court to win a plan that we can all be proud of.

Read the 60-Day Notice of Intent to Sue for Violations of the Endangered Species Act Related to Consultation on the Nantahala-Pisgah Land Management Plan.

Our members and supporters power our Resilient Forests program. Donate today, so we can continue to protect our old-growth and mature forests, which are critical habitats for many endangered and threatened species.

Press release from the Southern Environmental Law Center, MountainTrue, Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, Defenders of Wildlife, and Center for Biological Diversity:

For immediate release: July 26, 2023

Media Contacts:

Southern Environmental Law Center: Eric Hilt, 615-921-9470, ehilt@selctn.org

MountainTrue: Karim Olaechea, 828-400-0768, karim@mountaintrue.org

Sierra Club: David Reid, 828-713-1607, daviddbreid@charter.net

The Wilderness Society: Jen Parravani, 202-601-1931, jen_parravani@tws.org

Defenders of Wildlife: Allison Cook, 202-772-3245, acook@defenders.org

Center for Biological Diversity: Jason Totoiu, 561-568-6740, jtotoiu@biologicaldiversity.org

Conservation Groups prepare for lawsuit over Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan

ASHEVILLE, N.C. —A coalition of conservation groups sent a letter to the U.S. Forest Service signaling their intent to sue unless officials fix the glaring flaws in the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan that put endangered forest bats at risk.

On Tuesday, The Southern Environmental Law Center, on behalf of MountainTrue, Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, Defenders of Wildlife, and Center for Biological Diversity, sent a 60-day Notice of Intent to Sue, which is a prerequisite to filing a lawsuit under the Endangered Species Act. The letter explains how the Forest Service relied on inaccurate and incomplete information during the planning process, resulting in a Forest Plan that imperils endangered wildlife.

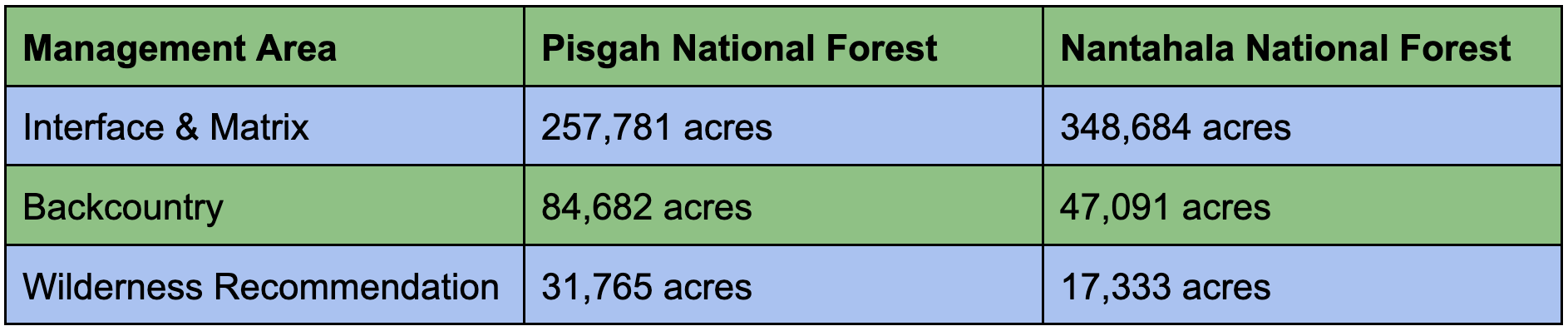

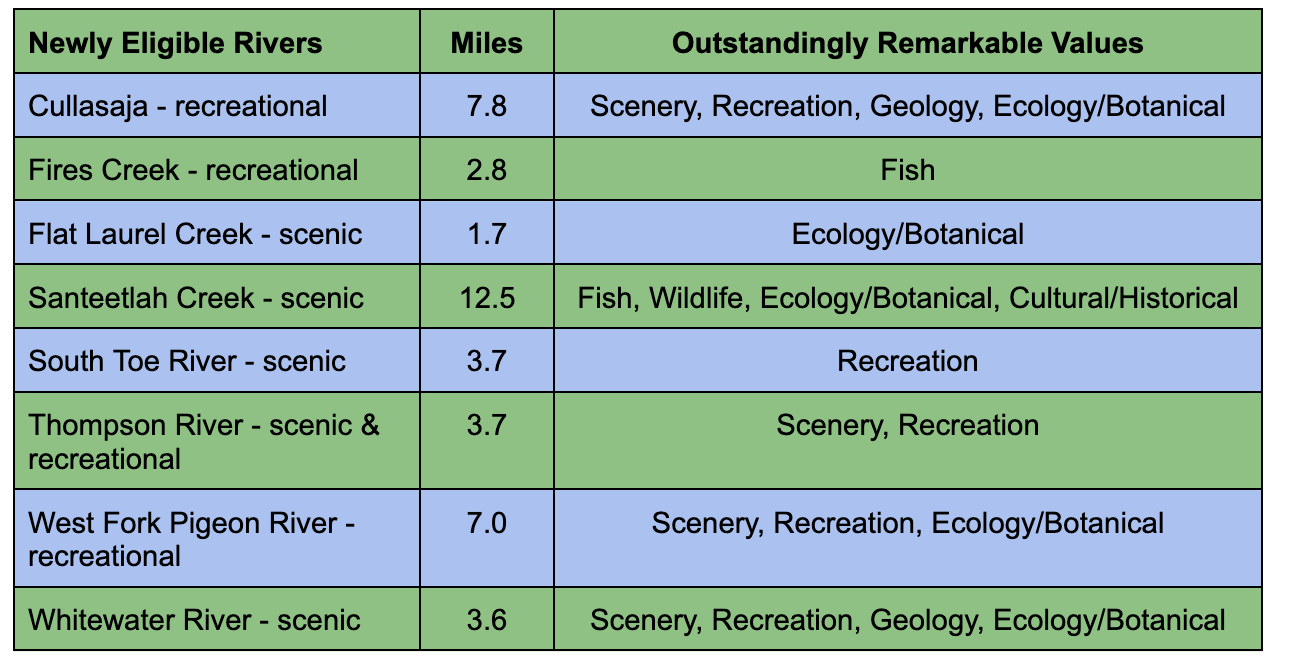

At its most basic level, the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan outlines where activities like logging and roadbuilding are prioritized and where they are restricted. The Plan, published in 2023, will have a significant and lasting impact on the beloved forests and the rare animals and plants that live there.

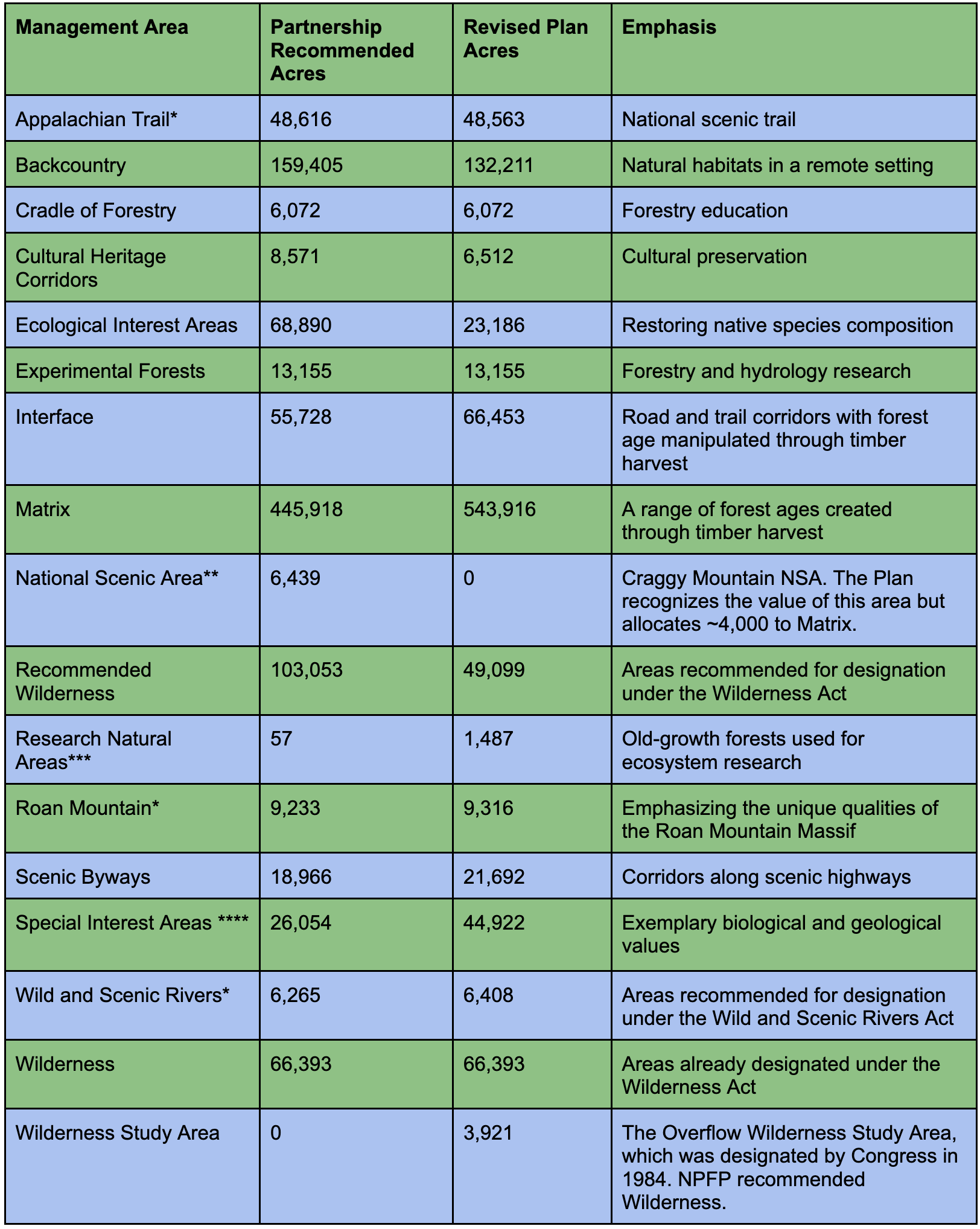

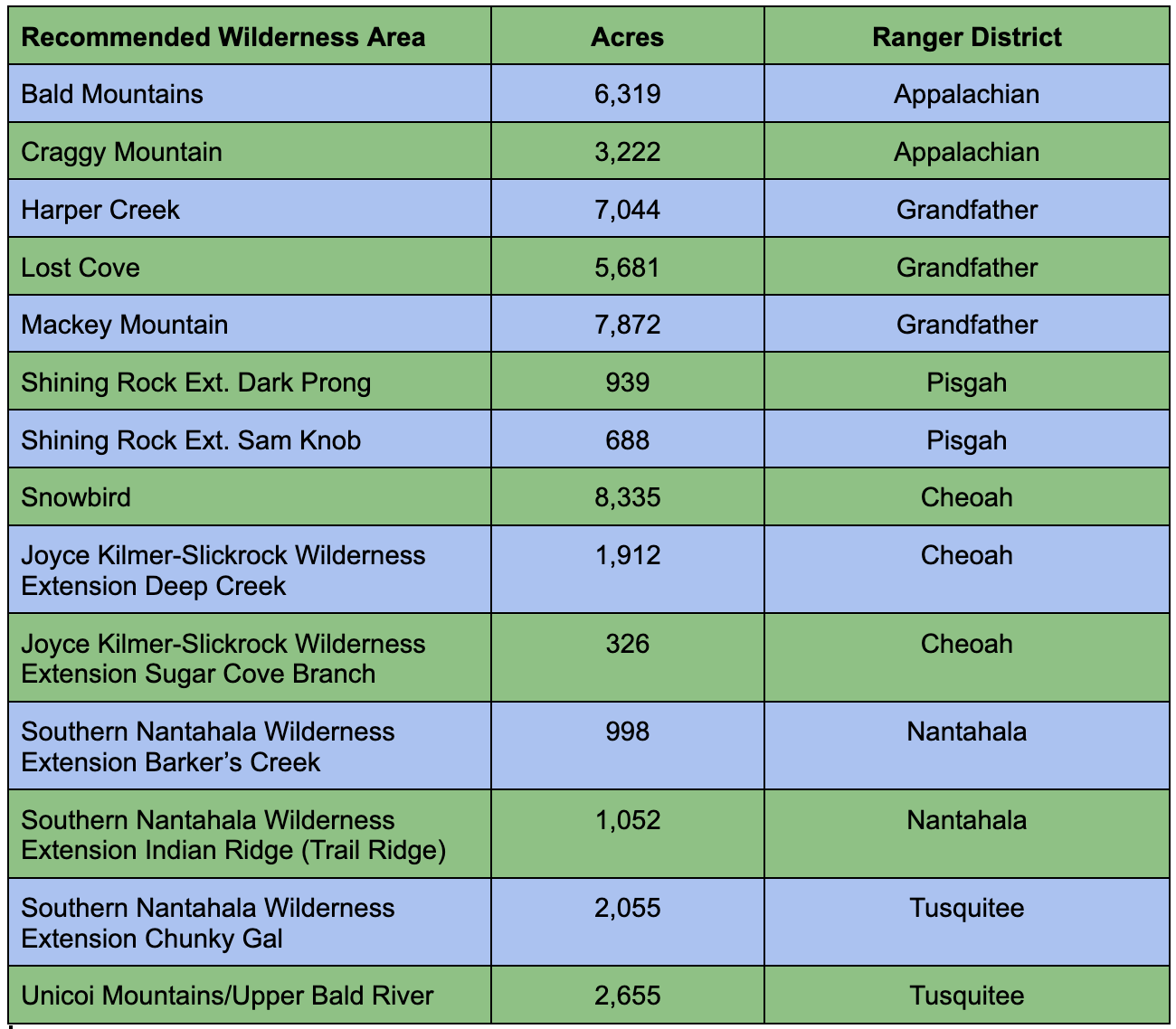

But even though these forests are a critical refuge for hundreds of rare species, the Plan prioritizes logging in the wrong places, even when it threatens endangered wildlife. For instance, some of our most critically imperiled bats are harmed by logging and need intact mature forests to survive. However, the Forest Plan aims to quintuple the amount of heavy logging, including in parts of the forest that are vitally important for forest bats. The Notice of Intent to Sue alleges the Forest Service had information showing increased risks to endangered species but withheld that information from the Fish and Wildlife Service, which oversees endangered species protection.

At every step of the planning process, the Forest Service ignored public concerns and the best available science about the new Plan’s harms to endangered species. Instead, the agency used misleading and inaccurate information to downplay the impacts this huge increase in logging in sensitive habitats will have on sensitive wildlife. The agency now has 60 days to reconsider its decision.

Below are statements from the Southern Environmental Law Center, MountainTrue, Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, Defenders of Wildlife, and Center for Biological Diversity:

“The Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests are home to an amazing diversity of animals and plants, including some of the most critically endangered species in the country. We cannot sit back while this irresponsible Forest Plan ignores the science, breaks the law, and puts these remarkable species at risk.” Sam Evans, leader of SELC’s National Forests and Parks Program, said. “Forest plans are revised only every 20 years or so, and our endangered bats won’t last that long unless we get this Plan right.”

“The Forest Service’s management plan for the Nantahala Pisgah National Forests is deeply flawed. The Forest Service put commercial logging first, ignored the best science available, and is needlessly putting endangered species at risk of extinction. Our incredibly diverse ecosystems deserve a better Plan. The people who love and use these forests deserve a better Plan. And MountainTrue and our litigation partners are willing to go to court to win a Plan that we can all be proud of,” said Josh Kelly, Public Lands Field Biologist for MountainTrue.

“The Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests serve as anchor points for sensitive habitat that protects a marvelous array of plant and animal species, which are increasingly under pressure. The recently released Forest Plan misses the boat for protecting key species by emphasizing activities that fragment and degrade habitat, especially for species that rely on mature and undisturbed forests. The N.C. Sierra Club will continue to work to protect the wildlife and habitats that we cannot afford to lose,” David Reid, National Forests Issue Chair for the Sierra Club, said.

“It is unacceptable that the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan puts imperiled wildlife at even greater risk of extinction. The Forest Service has blatantly ignored the best available science and shirked its legal duties to protect forest resources at nearly every step of the way in this planning process, leading to a Plan that prioritizes logging in the wrong places and trivializes intact mature and old-growth forest habitat,” said Jess Riddle, Conservation Specialist at The Wilderness Society. “At a time when wildlife species face unprecedented threat from the climate crisis, we must do everything we can to protect the biodiversity that we have. We need to use every tool in our toolbox to safeguard healthy, connected nature, including litigation, if necessary.”

“The Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests are home to several endangered bat species that have already taken a terrible hit from white nose syndrome, a deadly fungal disease that infects them while they’re hibernating,” said Jane Davenport, senior attorney at Defenders of Wildlife. “These bats rely on intact, mature forests to forage and to rear their young. Heavy logging in some of their last and best habitat on the East Coast may tip the populations over the edge. We must hold the U.S. Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service accountable for violating their Endangered Species Act duties to get the science right in the forest planning process.”

“It’s outrageous that this forest plan greenlights a fivefold logging increase in important bat habitat even as our bat populations plummet from disease, habitat loss and climate change,” said Jason Totoiu, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “This misguided Plan will destroy tens of thousands of acres and jeopardize species like the Indiana, northern long-eared, Virginia big-eared and gray bat. We will ask a court to step in to protect these highly imperiled animals.”

###